Release Date: April 12th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

As the Sniffles filmography gradually dims to a trickle, the Bookworm takes a bow in his third and final appearance. Toy Trouble serves as the second to last cartoon that bears Margaret Hill-Talbot’s name, followed only by The Brave Little Bat that same year; Jones’ directorial priorities were shifting, adopting slightly more abrasive methods of comic timing that outgrew the charming docility of Sniffles’ character. He would try his hand in shaping Sniffles to adapt to his faster, funnier, and at times more cynical cartoons (as has been mentioned before), but the writing was certainly on the wall that his time is numbered.

Toy Trouble—as the title suggests—is yet another “exploratory” cartoon, with Sniffles and his Bookworm companion scoping out the toy department in a department store. However, a hungry cat lurking nearby also seeks to partake in the festivities—festivities such as pursuing Sniffles and his friend.Paul Julian’s backgrounds are in top form from the establishing pan alone. The camera travels down the façade of the store, branded as a Lacy’s (an obvious parody of Macy’s whose name would be found in more than one Warner cartoon); his lighting attracts the most attention, as the glow of the lamps on the building feels genuine in its warmth and the slight reflections cast onto both the pavement and walls. One of his strongest points as a painter was his knack for lighting and handling highlights, inserting a palpable warmth into the atmosphere that proved beneficial for directors like Jones who sought out such an ambience.

“Warm” would indeed be the first word to describe the backgrounds. This short opens the same way a dozen of Jones directed shorts do: a muted façade cast in the nighttime, sleepy music gluing the visual cues together, a series of dissolves, pans, and truck-ins peeling back the layers to reveal where the main characters are hiding.

Yet, many of these synonymous introductions boast a feeling of coldness, loneliness, vastness—trying to evoke sympathy from a small character (such as Sniffles) having to traverse such an imposing landscape. It’s not to say that the dark, steely chill of these openings are inferior to the warmth of this opening, but the novelty of having such a comparatively inviting opening certainly proves to be notable.

Invitation evokes availability, which is certainly felt through a shot of elevator lights dotting above the door. Behind this introduction is a sense of purpose, from both Jones and the characters; it’s not as though Sniffles accidentally stumbled upon a toy store in the midst of finding shelter for the night. More accurately, having the elevator be running and stopping right in front of the toy department indicates he knows it’s there, he’s explored it once before, he and Jones both are ready to get down right to the chase. There’s a sense of admiration to be had in such preparedness.

Indeed, the elevator doors open to reveal its smallest—and only—passengers. Execution of the maneuver is delightful; the camera pans down at the same time the doors shuffle open, creating a very organic discrepancy of movement through two different forms of timing at once. Animation of the doors opening itself is a bit choppy in the process—the doors are timed on twos, whereas the camera keeps going every frame. This is to ensure that the timing difference is felt, maintaining that naturalism, but the spacing of the drawings with the doors themselves is very minuscule, as though it was intended to be animated on ones. Thus, the doors seem a bit choppy as a side-effect. At least in comparison to the smoothness of the camera panning down.

Still, it’s an incredibly tiny nitpick, and the reasoning behind it is understandable. Likewise, the unintended choppiness gives the elevator a mechanical feel, which is certainly helpful in distinguishing it from the smoothness of the camera or the organic, non choppy movements of its passengers.

One intent of the pan is to humor the audience with how out of place Sniffles and the bookworm look in comparison to the gaping elevator and store. This is a shot that explicitly intends to make them look and feel small—the camera isn’t at eye level to induce sympathy by seeing the world from Sniffles’ point of view. No beats about golly, this elevator sure is big, no dramatic layouts that justify the sense of awe the two characters share by exploring such unfamiliar territory. All of that will eventually come, but not now. In the moment, we are viewing it from the Chuck Jones point of view, the point of view that chuckles affectionately through the “fish out of water” effect evoked through the pip squeaks occupying such a big space not tailored for them in mind.

First impressions of the toys on display are not of blissful wonderment or a joyous explosion of color. If anything, it’s an air of mystery, restraint—the camera glides along to exhibit a glimpse of dolls, balls and trucks shrouded in deep, dark shadows. The tone never feels “scary”, either, with Stalling’s playful, flighty score of “Lullaby on Broadway” dictating a tone that is juvenile and earnest rather than suspenseful. The pan is instead intended to read as mystifying and perhaps even a little overwhelming. It seeks to elicit a question. It seeks to encourage Sniffles, the bookworm, and the audience to ask the same question: “What else lies ahead?”

“See? Isn't it just like I toldja?”

Sniffles’ joyous reassurances to his Bookworm friend cement earlier notions about the sense of purpose guiding this introduction. It hints at a backstory that gives such a simple little scenario some more depth—Sniffles has already been here once before, he’s done the aforementioned song and dance of stumbling upon this location and discovering its goods, and now he seeks to reap the benefits with a friend. A simple yet endearing motivation that adds a cushion or two onto the plot, gifting it some additional depth that intrigues the audience.

Keeping in line with the two Bookworm shorts preceding this one, the bespectacled insect doesn’t say a word. Instead, his jubilation is conveyed through affirming nods and a pump of the arms. Jones is able to harness the best of both worlds between Sniffles and the bookworm; the worm proves to be a helpful subject with indulging in pantomime. Meanwhile, Sniffles serves as the buffer, able to charm the audience through his actions and the vocal characteristics of Margaret Hill-Talbot.

Part of why the opening is as endearing as it is stems from Sniffles’ assuming a familial role with the Bookworm. Telling the Bookworm to stay put while he tends to some business, leading the way reads as an affectionate big brother planning a surprise for his impressionable sibling. Obviously, the two are only friends, but Sniffles behaving as though he’s the proud big brother brings a sincere dimension to their dynamic. Mainly because Sniffles himself doesn’t reek of “big brother” material (as evidenced in Sniffles Bells the Cat, a cartoon dedicated to depicting his older brothers picking on him as the runt), which is why it’s so endearing. The audience humors his gentle authority, inquisitive as to what it will result in.

Notions of preparedness even extend to the ways in which Sniffles MacGyvers his way through his obstacles, such as using a makeshift lasso to turn on a light-switch. Again, it’s as though he’s performed the ritual many times before and has spent an unforeseen amount of time off screen learning to perfect the art of breaking and entering into toy stores. With his meticulous planning, his preparation, and his paternal instincts comes a charming overzealousness that exudes pure innocence.

Innocence moreover extends to the “reveal” of the toy department, which is handled flawlessly. It’s such a painstakingly simple maneuver that it doesn’t seem like much of anything on the surface level: Sniffles turns the light on, thus ushering in a stagnant shot of the toys all aligned on the shelves. That’s it.

Is it, though? What makes its introduction so profound is how personal it feels. Close-ups of Sniffles tugging on the rope, flipping the switch and turning his face to look at the store almost takes more time than the shot of the store itself. Delegating that much screen-time to Sniffles over, say, the light turning on (instead, it’s only hinted at—the lighting changes and a click is heard as we look to Sniffles instead) or shots of the toys becoming illuminated dictates a more personalized, human, empathetic angle by placing a focus on his reactions and motions.

His grin and the swelling music score of “All This and Heaven Too” are, again, stupidly simple, but incredibly strong in their simplicity. The directing oozes such a palpably innocent sense of wonderment that the audience can’t help but share.

To me, personally, this opening—and the reveal especially—is more effective than any toy themed cartoon we’ve encountered thus far with vaudevillian toys singing and dancing. It’s carried purely through the genuineness of Sniffles’ reactions and impulses, whether that be turning his head to gawk at the toys or the earlier notes about his eagerness to show off and display his preparedness. There’s just something about his readiness in wishing to indulge in a secret he’s curated for himself, finally ready to share it with another confidant (which includes us) that is so incredibly charming and personal. It may not be uproariously funny, or eye bogglingly captivating, nor stunningly drawn.

Really, it’s a very simple and—from the surface level—totally unremarkable piece of business. Yet, Jones, ever the empath, is able to inflate it into something more by allowing the audience to step into Sniffles’ shoes and look from his point of view. That personalization, that intimacy is what encourages the audience to question, to wonder, to be curious about what the department has in store. A deceptively menial, minute portion of the cartoon that is one of my favorite takeaways from the short and epitomizes all of the aspects I love about early Jones.

The Bookworm shares the same sentiments of awe as Sniffles, as he’s the first to actually go explore and get a glimpse at the toys up close. In effect, this means accidentally leaning on a switch that activates a tin jazz toy (whose poignant blackface was unfortunately common regarding these toy cartoons, which, inevitably would feature the same jazz toy).

Rather than be startled at his unforeseen activation, the bookworm is thrilled. Execution of the toy band itself is very nice—the razzing musical accompaniment of “It Looks Like a Big Night Tonight” is tinny, high pitched, frenetic to indicate its juvenility in being a toy but still has enough orchestral vestiges to justify the worm’s wonderment. Likewise, movement on the jazz players is mechanical and stilted in every positive connotation of the word. It’s a metallic toy—it shouldn’t be an elaborate showcase of squash and stretch, easing in and out, follow through, and so on. Movements are abrasive and rigid, but out of purpose and aspiration rather than shortcomings in draftsmanship.

Capturing the feeling of the toys suddenly frozen in suspension is executed just as well when Sniffles rushes over to turn it off; the toys don’t immediately freeze in their last known positions, but, rather, sink somewhat gradually into a position that still supports their stiltedness. Of course, all of this happens only in a matter of seconds, proving difficult to digest every iota of animated information available. Regardless, it is very well handled and asserts a noticeable divide between the organicism of the bookworm (and Sniffles) and the geometric mechanicalness of the toy.

“Now listen here!” Sniffles politely assumes his role as the protective big brother, which is affectionately hinted at through Stalling’s fitting backing track of “‘Cause My Baby Says It’s So.” “You stick with me. And don’t touch anything else, or you’ll get into trouble!”

Mention of getting into trouble indicates a sort of awareness that previous Sniffles cartoons in a similar vein didn’t have. For example, The Egg Collector had a naïve, happy-go-lucky Sniffles strolling into the eaves of a church to find an owl’s egg, completely oblivious to the dangers his role as a trespasser plays. The Bookworm assumed the role of the anxious sidekick, clearly averse to exploring. Now, the roles are inverted, with Sniffles being the one to keep an eye on his friend. This “trouble” is abstract, but holds enough gravity to assert that there are stakes involved. It renders the hook enticing through the inherent thrill of doing something you’re not supposed to be doing.

Thus, the two trek forward. Such cues Jones to initiate the exaggerated layouts he’s been keeping under the surface until now—toy blocks stacked on top of one another are transformed into a looming, almost ominous landmark. An upset in balance could be catastrophic. Warped perspective is dynamic, engaging, and empathetic as a completely menial afterthought to us humans is a beacon of awe and even respectful intimidation to the Bookworm and Sniffles.

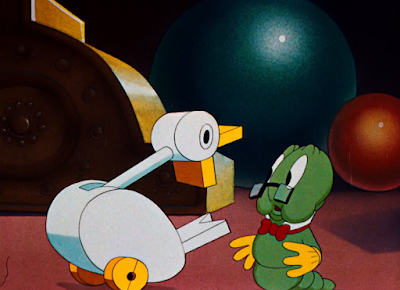

So entranced in the scale of his surroundings, the Bookworm is completely oblivious to the toy duck he’s backed into. That in itself seems innocuous; it’s a wooden duck only slightly bigger than he is. Yet, the sudden convulsions that follow indicate there is more than meets the eye.

Indeed, the misadventures of this seemingly anodyne mallard are chronicled for the next minute of the cartoon. Perhaps to some tedium. Still, the surprise aspect of this wooden duck being able to quack, pop, and convulse is captured well. Similar to the jazz band, movements of the duck are handled abrasively and with rigid caricature, moving in extremes from one pose to the other. It’s meant to be unpredictable and purely artificial. Likewise, Treg Brown’s sound effects are given a special spotlight throughout the time that the duck is on screen—Stalling’s music score is nowhere to be found. Just pops, clangs, and quacks that support the playful zeal of the animation very well, but does begin to wear out its welcome.

The duck is intended to be a nuisance, so some of that comes with a purpose. After scaring the Bookworm into a nearby jack in the box (a gag that again seeks to reap the benefits of this warped sense of scale, the clown towering like a giant as the worm helplessly clings to its cherry red nose), the wooden mallard opts to pursue Sniffles in its autopilot frenzy.

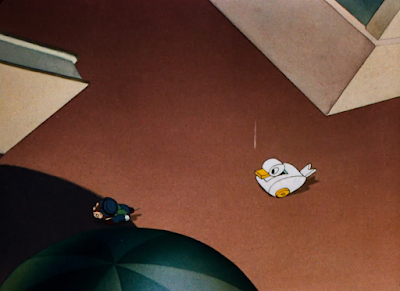

A particularly memorable shot stems from the duck racing right at the camera. Stylization takes the forefront; the ground is completely black, the horizon a dusty orange with no details in sight. Orange evokes alarm, warning—the black is bold, jarring, unnatural, and the complete lack of any decorations or furnishings elsewhere places full focus on the duck hustling full speed at the camera. We see what Sniffles sees, and that translates to danger. Completely stalling the music score (just the ominous, rhythmic clangs and quacks) instills a further note of anxiety that wouldn’t have been as poignant if it had been obscured through a jazzy, raucous chorus of chase music. The effect is genuinely unsettling.

That same unease permeates Sniffles’ attempts to escape. Perhaps not so much in the shot of him hiding between some books (which also looks nice on screen, with Sniffles briefly running into the foreground as he makes the turn to give further depth to the composition—ditto with the construction and perspective of him peeking his head out from between the books), but the overhead shot of the duck on his trail.

There’s no harm that the duck could possibly cause. It quacks. It clangs. It dings. From a human’s point of view, it’s an incredibly tiny toy that just happens to make a lot of noise. Still, it isn’t exactly intended to be as aggressive nor threatening as it is confounding. Its unease stems from the unknown, as there isn’t a clear answer as to how it is activated or deactivated, how it knows to pursue Sniffles and why.

Moreover, it doesn’t seem to follow any “rules”. Such is particularly noted through a shot of Sniffles and the duck peering out from adjacent books to look for the other. Sniffles taking refuge and hawking a cautious glance is a given; the duck, now silent, craning its wooden head with purpose and caution is not.

Parallels between the organicism of Sniffles and the synthetics of the toy are direct and strong. Perhaps a bit too strong; whereas Sniffles is timed on twos (which is standard), the duck is held for four, five, occasionally six frames each to accentuate the rigidity of its movements. A very conscientious detail that evokes a strong juxtaposition against the organicism of Sniffles’ movements, but the effect on-screen looks choppy and disorganized. It doesn’t read as mechanical so much as it does as a timing error, even though it was very purposeful. Coloring the books to be indicative of their “owners” (a reddish brown for Sniffles, matching his brown fur and the cream to match the duck’s white paint) proves to be a more visibly effective—albeit subtle—parallel.

Digressions aside, the sudden anthropomorphism of the duck is amusing again through such unpredictability. Even the audience doesn’t know how the duck “works”—it’s sentient until it’s not. Viewers share the same puzzlement and surprise as the characters on-screen, arousing a sympathy and attachment through such vicarious feelings.

Quacking and clanging still continues, as do shots of the duck racing around as Jones reuses that same onward shot. Occasionally, the noises of the duck rise in pitch to ease some of the monotony; it informs a crescendo in action, as though the higher the duck’s quacks, the more ferocious it becomes. Likewise, it almost seems like a confession from Jones. It’s as though he understands this bit has become played out, and seeking to keep it interesting by changing the pitch of the sounds is an acknowledgment of such. It should be noted that this is, of course, not the last time we see the duck in this cartoon, but the shifting to priorities as the Bookworm approaches an electric train set is somewhat telling on the duck’s fading novelty.

Focus is instead delegated to the train set, which is accidentally activated as a side effect of the duck’s aimless pursuit. Having both the train and the Bookworm lunge right towards the camera again elicits notions of immersion and sympathy as the audience is thrust into that same action. Speeds of the train are domestic, but they don’t need to be much more than that. It’s a toy. The Bookworm treating the oncoming toy train like it’s a real threat—because to him, it is—seeks to be the main novel takeaway more than the intricacies of the train’s mechanics. Stalling’s musical accompaniment is alarmed, but playfully and jovially so rather than truly panic stricken. We humor the worm’s anxiety and attempts to escape rather than truly share it.

Some of Tex Avery’s influence can be felt through the train chasing the worm—ironic, given that his and Jones’ films were pretty divorced in tone from each other. Here, the worm and train entering a tunnel, only to come out with their positions swapped (the train now in front, worm in back) is a direct mirror to the same gag in The Crackpot Quail. It’s more cute and charming here than uproariously funny and confounding, as is the tone in Quail, but that is largely owed to the context surrounding the gag rather than execution itself. Even with Jones still in the midst of his “Disney influence”, as many liken this period to, Avery’s influence still finds a way to permeate the inverse of his own cartoons.

So much so that the gag is the main takeaway from the sequence. Rather than showing the worm jump off the tracks or have the train miraculously come to a halt, both are abruptly ushered out of the scene with a quick fade to black. It’s a very sudden transition that feels disarming in a way unintended; perhaps that could be owed to the nonchalant execution of the gag. It’s noticeable and it’s amusing, but not sustainable enough of a note to end on.

Likewise, shifting to Sniffles stagnantly observing a toy doesn’t seem “important” enough of a change for the Bookworm to get curtains, but one does have to remember this is a short centered on toys. Where there are toys, there are toy related gags.

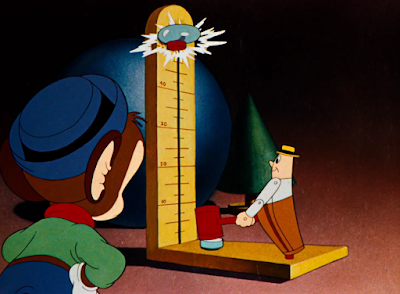

In this case, Sniffles studies a strength tester toy: a tin man with a mallet hits the button, prompting the slider to ring the bell, fall back down, rinse and repeat. It exists mainly as an opportunity to usher in a gag with Sniffles’ eyes tracking the movements of the arrow, his pupils substituting as the slider and cavorting within his eyes. Some of the movement at the beginning of the scene is aimless, his eyes moving in an arch that isn’t indicative of any of the action on-screen, but the actual mimicry of the strength testing action is quaint and politely amusing. Stalling’s ability to instill a circuitous rhythm into the action proves to be the most impressive takeaway.

Sniffles too is given the hook just as the Bookworm was, another fade to black indicating the sequence’s role as a tangential vignette and nothing more.

Fading back to him encountering a stuffed cat proves to be more substantial in its purpose. Already, the audience is able to piece together where this is going to go. The design of the cat is synonymous to the one seen in Sniffles Bells the Cat; a very faint dark stripe on the top of its head serves as the only signifier that it’s a different entity.

“Gosh! For a minute, I thought it was a real cat!” Sniffles’ dialogue is a little obtuse, probably able to favor from a more subtle means of identifying the feline. Still, his aside is directed plainly to the audience, both from the direct eye contact (which is handled very nicely—the drawings of him looking right at the camera are full of appeal and charm, his big pupils radiating a certain warmth that isn’t always present with the occasional uncanniness of characters staring right at the camera) and the exactness of his dialogue. It’s very much a statement rather than a natural piece of dialogue elicited from a reaction.

“Golly, they sure do make ‘em… lifelike, don’t they?” is a more organic line that could have substituted the first statement just fine. As he talks, there’s a brief pause and stutter in his vocals—such taps into the previous praises of Talbot’s deliveries and Jones’ vocal direction in Bells the Cat, where these sort of naturalistic pauses and hitches were commonplace. It instills a natural charm and earnest, making Sniffles seem more soft-spoken and endearing through such organic speech patterns. Those little quirks aren’t nearly as concentrated here as they were in Bells, but any inclusion at all indicates a purpose in Jones’ vocal direction. An intended decision rather than a flub that they decided to go with.

Predictably, the cat’s eyes open once Sniffles has exited the screen. Comments about the cat’s “lifelike”-ness” are justified through the construction and solidity of the animation. While the cat doesn’t move much on screen, its tightness and structure is still exceedingly visible—the effect wouldn’t have been the same if a less competent animator were cast with the challenge. (Part of the cat’s haunches erroneously inked white for a few frames are unrelated to comments about animation quality, but still prove intriguing to identify.)

Rather than stretching out the time between Sniffles walks past the car and when he notices it through the remainder of the short, Jones cuts right to the chase. It still takes a little bit for the dime to drop (in typical Sniffles fashion, who isn’t a character who operates at a particularly fast pace), but more time is spent fleeing and hiding from the cat than second guessing if he’s actually real or where he could be.

“It sure is… marvelous what they can do with machines these days,” says Sniffles after a liberal amount of similar statements. Momentum drags a bit, sure, but Jones seems more preoccupied with milking the charm and availability of Talbot’s vocals. All the pauses, all the gulps, all the flimsy reassurances.

Execution of the cat attacking spawns a somewhat incoherent slew of shots. Perhaps “incohesive” is the better suited word, as it isn’t difficult to discern what’s happening: the cat lunges after Sniffles, who runs away. We get a glimpse of the worm chasing/“fleeing” the same toy train in the process. Still, the flow of shots feels sudden in a manner that suggests disorganization rather than a purposeful embrace of a climax or adrenaline fueled chase. Focus seems somewhat skewed; the cat feels as though it is pursuing Sniffles out of sheer obligation rather than natural impulse. Everything just seems to unfold in a somewhat cold, dutiful, quick manner that leaves the viewer blind sighted. There was more conviction behind the toy duck chasing both Sniffles and the Bookworm than there is following the cat.

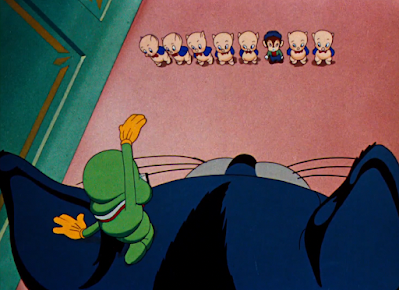

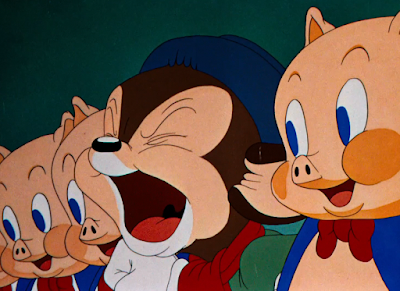

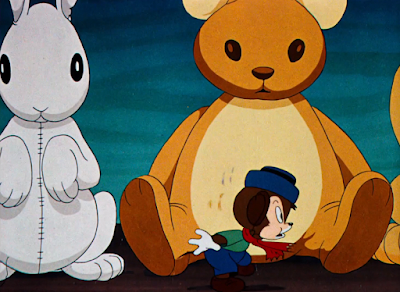

Still, uneven as the directing may be, it does result in one of the most notable takeaways of the cartoon (and one of my personal favorite scenes.) Porky Pig appears only for the second time in a Chuck Jones cartoon—third, if one were to count his face on a line of books in Sniffles and the Bookworm—as a line of toys, flanking Sniffles’ sides as a means of disguise. Even through such a menial cameo, it’s fascinating to track the design evolution of Jones’ pig. He retains the pronounced rosy cheeks from Old Glory, but boasts much more organic shapes and proportions, particularly in the head—less bulbous and geometric than in 1939. A pronounced collar on his jacket is, likewise, a nice touch, as is the blue eyes harmonizing with the color of his coat. Everything about the drawings of these dolls is infinitely more appealing than how he looked in his previous outing with Jones (though not to discredit the hypnotizing animation of Bob McKimson in that cartoon.)

A guttural porcine bias very well may influence this deduction from yours truly, but the segment involving the dolls is one of the strongest in the cartoon. Novelty of the Porky cameo is certainly a bonus and partially influential in such a ruling, but it likewise features a little bit of everything that makes Jones’ directing so likable: great music from Stalling (a saccharine string orchestration of “In an Old Dutch Garden”), incredibly sculpted and tactile animation, character beats where emotions permeate the screen and elicit amused empathy from the audience, and very naturalistic voice direction to generate further warmth and charisma.

Animation of the cat poking the dolls is well executed; the paw is chiseled, constructed, dimensional, whereas the dolls possess an antithetical squishiness in comparison to cement the very real sense of weight being applied with each poke. With each squeak, the faces on the dolls slightly contort to appear surprised; such gives the actions of the cat more gravity than what would be present if the mouths remained in a smile.

Sniffles, however, does retain his smile—ironic that the dolls arguably show more “emotion” than the actual living, breathing mouse. He’s the third victim of the cat’s poking, following the rule of threes for a satisfying punchline rooted in rhythm.

“Mama!”

As soon as the words leave his lips, he recognizes his mistake. Porky dolls squeak. They do not say “mama”. Thus cues an incredibly human piece of acting as Sniffles grapples with his folly; the tense stare down at his feet, the clearing of the throat, the cautious, aware blinks as he dares to cast a glance towards the cat, the subdued “…uh…” following his revised proclamation of “Squeak!” It looks, moves, and sounds believable, it’s filled with charm, and—most importantly—it’s a genuinely funny beat. Awkwardness permeates the screen in a manner that is endearing rather than excruciating. Such is a very delicate balance to achieve.

Dismissal outweighs the pointed suspicion of the cat as he leaves his prey be. Animation of him turning around in the frame is rather sophisticated and full, again remarkable in its construction; turning towards the camera rather than away from it places the dimensionality of the motion in the forefront.

Similar comments apply to Sniffles making his own cautious escape, veering towards the foreground in a way that suggests depth within the composition. Motion of his tiptoeing is balanced, tactile, sincere in its cautious and restrained application of weight.

Both the audience and Sniffles should have known that the cat leaving then and there was too easy of an escape route. It is. Such a gesture furthers the sentience of the cat, in that he’s even wise enough to know when and how to fake-out his prey—it likewise cements that Sniffles’ disguise is as flimsy as he initially thought.

The solution? Transform into a toy soldier. Kudos to the animator, who contrasts the organicism of Sniffles’ movements with a newfound rigidity in a matter of seconds. Watching him immediately perk into position establishes a means of comparison—we know what he looks like when he’s in a normal stance, and we know what he looks like when he’s ridiculously on guard. Demonstrating such a juxtaposition in real time renders the punchline of his rigidity more amusing and effective by being able to see what he looked like before.

One aspect of his faux-soldier stance isn’t more effective than the rest. The thousand yard stare, the tidy silhouette with the puffed out chest, and the actual movement as he teeters back into his place, supported by the playful mechanicality of the music chorus courtesy of Carl Stalling support Jones’ vision in equal tandem.

An additional “squeak!” for good measure rouses a laugh from the intended dissonance. Sniffles is entangled in a toy-themed identity crisis, channeling an amalgamated approximation of toys rather than sticking to one or the other. Mechanical tin soldier toys do not squeak. In the midst of a life or death situation, that isn’t important.

His disguise—a term used very liberally—ends up digging his grave; rooted into his position, a target of the cat’s unmoving stare, he doesn’t have the freedom to warn his Bookworm friend about the cat. Something that proves to be rather pivotal when the Bookworm finally escapes his autopilot train fleeing and mistakenly climbs on the cat to rest.

Evidenced through cartoons such as Sniffles Takes a Trip and Joe Glow, the Firefly, Chuck Jones enjoyed having small characters climb on big things. It grants an opportunity to experiment with perspective, hone in on extraneous details that a regular, run-of-the-mill layout wouldn’t have the luxury of indulging in, and it evoked a shared sense of sympathy and wonderment through being able to look through the eyes of the character on screen.

That same self indulgence is present here too. Jones makes an attempt to split the perspective evenly—the dramatic angle of the worm peering over the cat’s head down to Sniffles and the dolls below, as well as an up-angle of Sniffles only seeing the menacing expression on the cat below the worm. That way, the audience is able to assess the situation “fairly” and gather both perspectives—accentuate the height and danger of the worm, and put an emphasis on Sniffles’ urgency to get him down.

Sniffles ends up vocalizing his warning of “THE CAT!!!!” through complete accident. The first two times, he mouths it, much to the oblivion of the worm. Even the audience is able to see that Sniffles’ lips—made the focus through an intimate layout that angles the camera right towards his mouth—mouth out “the cat”. Thus, his outburst is surprising not because it’s a new piece of dialogue, but shocking at the aspect of Sniffles letting his guard down and what that means for him.

Awkward, shameful finger plucks from the Bookworm are orchestrated to an equally plucky sting of “You’re a Horses Ass”; his feelings on the matter are clear.

More early Jones trademarks manifest in his encounter with the cat. As mentioned in the analysis of Joe Glow, there seemed to be a fixation from Jones with characters staring and interacting with the enlarged eyes of other persons. Rather than leaning or pulling up on an eyelid, as Jones’ prior examples of this phenomenon entail, the worm cuts straight to the chase by tugging on the skin around his eyes entirely—a much more direct confrontation. A slow, slithering grin sheepishly making its way onto the worm’s face is likewise rife with Jones’ behavioral sensibilities of the time.

Handling of the cat casually plucking the nuisance off of his eyes is solid; the audience can feel the tugging effect once the worm is finally free, making the worm seem like even more of a nuisance and potential piece of dead meat for aggravating the cat.

Discarding the worm into a nearby chemistry set indicates that the cat isn’t interested. Instead of being hurt physically, the worm must nurse a wound that targets his pride instead as he’s shoved into the test tube. Then again, given the worm’s demure demeanor, wounded pride doesn’t seem like an issue he has to confront too often. Previous shots depict the chemistry set in the background so as not to disarm the viewer completely with this new development.

Worms aren’t a substantial source of protein. Mice, on the other hand, are; a conniving grin on the cat’s face as he saunters towards his prey indicates that Sniffles isn’t going to receive such a dismissive treatment. Disentangling from his fleet of pigs, he does his best to make an exit that is productive but unassuming. Anxious glances behind his shoulder as he continues to tiptoe backwards are a very human, organic touch that give added believability and heed to his actions.

It helps that a familiar clanging, clacking and quacking sound offers something to look at to begin with. Indeed, Jones gets all the mileage he can out of the reused shot of the toy duck hurtling towards the camera—it has been rocketing around the interior of the toy store this whole time. By this time, Sniffles become intimate enough with the adversarial toy to know how to dodge it.

His other adversary, however, hasn’t. Thus, the main climax doesn’t occur between Sniffles and the cat, but the car and the duck. Or, more accurately, the cat attempting to escape from the duck.Thus presents an opportunity to wrap every idea established by the cartoon (plus some additions, such as the cat sliding on a xylophone); the jazz band, the tower of blocks, the train, and the strength testing toy all serve as either an obstacle or a bystander. Revisiting ideas established earlier, even the most tangential of vignettes, strengthens the overall cohesiveness of the cartoon.

Granted, the clarity of these tangents differ. Blocks spelling the words “ZOOM!” as the cat rushes past is a synthetic, controlled act that is amusing through its perfection. As much of a stretch as it may be for the blocks to align so perfectly, it isn’t completely impossible.

Conversely, stuffed animals magically forming hands and gesturing like hitchhikers in the wake of the cat’s speed, a commentary on how fast he’s rushing by (as though the wind behind him caused their limbs to sway in a manner that suggested hitchhiking) requires a strong suspension of belief. The action feels too purposeful, too guided—there are too many actions for it to communicate and read, and those actions all seem very purposeful. The contorting of the hands, the bend of the fingers, the support in the arm waving back and forth.

The strength tester going bonkers in the cat’s wake falls into the same territory. It’s a cheat and an approximation first and foremost—these are commentaries on the chase more than meticulous demonstrations of toy physics. Still, it takes a bit more convincing than a gust of air to prompt the toy to hit the bell with such freneticism.

Crashing into a pile of blocks (after receiving an involuntary ride on the train) promote another amusing gag in the vein of “ZOOM!”, with the toys spelling “HELP” instead. “OUCH” probably would have been suited for the context, as “HELP” evokes stronger feelings of sympathy and pity. Not that the cat isn’t deserving of it, but he is established as the short’s antagonist, after all. Having the duck chase him away is seen as an act of liberation, a relief that he will soon be out of Sniffles’ hair. The feebleness innate to such a cry for help makes the audience feel bad for him, which negates the impact of his departure. In other words, it communicates as uncomfortable more than funny. Sharp eyes will catch that the cat’s eyes are erroneously inked white instead of yellow for a few frames.

Resolution of the climax is another bookend in itself, but one that is admittedly sudden and a bit empty. The last known whereabouts of the cat are depicted through the façade of the elevator that opened the cartoon to begin with—lights flashing towards the bottom floor indicate the duck has chased the cat into the elevator and sent it plummeting to the ground level, thusly out of sight. No shots of the cat nor toy entering the elevator and how it was shuttled down as quickly as it was. Granted, all of the necessary information is communicated right through the shot of the lights—very economic and clever, but to leave off from that and suddenly dissolve to Sniffles evokes a feeling of dissatisfaction and mild confusion. An anticlimax of sorts. Even just Sniffles making amends with the toy duck for scaring off his prey would have helped to bridge the gap, if only slightly.

Instead, focus is affectionately shafted to the Bookworm. Our final glimpse of the little fella in animated form is not particularly favorable to him, but amusing and endearing for the audience—that includes Sniffles. Slowly he inches along, the iris enveloping him to put an end to his shame as he edges forth, still stuck in the toy test tube. A symbol of his discarding.

Admittedly, Toy Trouble isn’t one of Chuck Jones’ most structurally sound efforts. Many of the shots feel tangential in a way that is sort of loose, aimless, even in spite of the climax’s best efforts to wrap everything together. It’s a showcase more than a coherent story, and any conflict that occurs feels obligatory rather than truly earned. A cat chasing a mouse is the least of the cartoon’s surprises, but having a random cat just happening to lurk in the toy store seems like a pretty big plot contrivance. Convenience is more transparent than what could be helpful.

With that said, I still like it. You have to have a pretty black heart to froth at the mouth over a cartoon about toys. Strengths of the short are particularly resounding, whereas it’s weaknesses are likewise just as crystallized. The opening and the coinciding earnest is incredibly strong and effective in charming the viewer; likewise, everything about the sequence involving the Porky dolls is perfect. All throughout the cartoon, there’s a reigning whimsy that is sincere and inquisitive. Drawings are solid, tight, appealing, motion is believable and rhythmic, weighted. Layouts evoke the emotions necessary to best support the tone, whether that’s awe, anxiety, or mischief. Talbot’s vocals never once lose their charm. The same applies to Stalling’s orchestrations.It’s a short that has its flaws. Just like any short. It has its ups and downs, pros and cons. There are other Sniffles cartoons that are more effective in their respective departments—if one were looking for atmosphere and ambience, they could turn to Sniffles Takes a Trip, whereas personal characterization and charm regarding Sniffles as a character is more palpable in efforts like Bedtime for Sniffles and Sniffles Bells the Cat. Little Brother Rat still remains one of the best in terms of a prioritization in story. This short isn’t exactly a standout for those reasons, but remains too innocent, too charming and too attractive to dismiss. Again: a cartoon about toys proves difficult to find a genuine problem with.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)