Release Date: March 29th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Manny Perez

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Bear, Dog, Mouse, Cow), Georgia Stark (Whistling)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

As hinted through the past few reviews, the opening title cue accompanying Porky’s Bear Facts is more significant than most. Particularly because it ushers in a new arrangement that would remain through Behind the Meatball—a short released in April 1945. To have the same title cue for a stretch of over four years has been unheard of, at least for Warners; slight modifications to the orchestrations would be made in conjunction with a new title card at the start of a new cartoon season. That line has somewhat been blurred within the past few months of Warner cartoons. The tides are changing.

Nonetheless, there are more pressings “firsts” to welcome over a shift in musical arrangements. “Firsts” such as the first animation credit of Manuel “Manny” Perez.

Many of these introductions for a new animator have felt temporary in the past few years. These shorts and these artists were still young, and “stability” wasn’t necessarily a common word at this point in time. Artists move, whether that be from unit to unit or studio to studio. Artists get demoted, artists get fired. I myself only just found out that Dave Hoffman didn’t “vanish off the face of the earth” like I had previously assumed, considering his credits dried in the cartoons completely—studio newsletters confirm he was still within the studio as of both 1947 and 1955, implying he got demoted to anonymity as an assistant animator.

Manny Perez is a refreshing exception to this recent pattern. Having worked at Warner’s since 1934, he would become a fixture of Freleng’s unit, staying with him all the way until the 1953 studio shutdown. Likewise, he would momentarily work under Bob McKimson’s direction after Art Davis’ demotion from director landed him back into Freleng’s unit—thus, the unit had exceeded its capacity, and Manny was the temporary sacrifice until Gerry Chiniquy’s departure granted him entry back into the Freleng’s unit.He being the chosen one to leave Freleng’s unit was not by coincidence. Unfortunately, Manny and Freleng did not have the most amicable of relations; even their coworkers, such as Virgil Ross, took notice, with Ross pinning Manny as Freleng’s “whipping boy”.

Ironically, Manny would continue to work for Freleng at Depatie-Freleng Enterprises through a good chunk of the ‘60s and early ‘70s. That experience, coupled with over a decade spent in Freleng’s unit, justified this comment he shared with Greg Duffell: “You know, I worked so long for him. ... well ... I got to hate that little guy…”

Thankfully, Manny’s career is not defined solely by his contention with Freleng. Following his departure from Warners, he did some commercial work at Ray Patin’s studio before shifting over to Hanna-Barbera, where he contributed to The Huckleberry Hound Show and Quick Draw McGraw. Likewise, he had the honor of working on a few of Bill Melendez’s Peanuts specials, including A Charlie Brown Christmas. He would spend his later years collaborating with the likes of Ralph Bakshi, Filmation, Sanrio Productions, and Ruby-Spears. Quite a prolific career.

We therefore dive swiftly into Porky’s Bear Facts—the first Porky short released in over two months, which was unheard of at the time. Moreover, it’s the first Freleng directed Porky short in around four months. Ditto for being Mike Maltese’s introduction to the pig.

If anything, this is really only a Porky cartoon in name; the real stars of the short are his indolent neighbors. A spin on the time honored fable of The Grasshopper and the Ant, Freleng and Maltese present two parallels: Porky, the dutiful ant who reaps what he harvests sows, and a bear and dog, the grasshoppers who take pride in their sloth—until it nearly kills them.

The introduction of the cartoon served as a reminder of changing tides. Not because it is particularly groundbreaking—rather, it’s almost a regression. When was the last time that the opening two minutes of a Warner cartoon was completely dominated by song?

This is, by absolutely no means, a complaint. In fact, the songs are instrumental in establishing a very foundational theme of the short: parallels. In this case, we are introduced to Porky first, who appropriates the lyrics of “The Girl with Pigtails in Her Hair” to fit the contextual demands of the short. Plowing along with his trusty steed (who marched along at a commendable pace of musical synchronization), Porky echoes his maxim to the world: you re-re-reap what you sow.

Herman Cohen appears to be the chosen animator for this establishing scene. Given the volume of his work in You Ought to be in Pictures and Porky’s Baseball Broadcast especially, where he was the sole animator of the character in the latter cartoon, it doesn’t seem to be much of a stretch to speculate that Freleng cast him as the “default” for Porky. That is, assign him scenes that are more straightforward and could stand to have some added charm or general liveliness. Cohen’s work at this period is understated, but in all positive aspects of the word—it’s competent, it’s constructed, it moves and behaves believable with an organic charm. He maintains a fine sense of control in his draftsmanship that certainly isn’t taken for granted.

While he certainly needs no introduction nor elaborate justification, Stalling’s arrangement of the song is bright, alert, and chipper. Whether it’s accompanying the visual of hens laying eggs through the tactility of a xylophone, or something more subtle—such as the flute glissando upon Porky’s lyric of “watch them grow”, representative of a crop sprouting out of the ground—the song feels motivated and comfortable in its usage. It’s not to say that the thought wasn’t on his mind, but the song number doesn’t feel like Freleng’s solution to padding out time in the short. It offers a versatile and cheery way to introduce the theme of the short and warm up the viewers with some additional laughs.

Case in point: a small hen whose egg laying is much more akin to a meticulous balancing act than a routine bodily function. It isn’t so much the plethora of eggs coming from such a tiny body that’s amusing—even at this point, it was old hat—but the visual of the eggs arranged in such an unnatural, physics-defying placement. Stalling’s xylophone accompaniment gives a permanence to the action, allowing it to live in the cartoon, whereas the rule of threes with the other two hens preceding the third normally introduces a rhythm the audience can digest and interpret. Likewise, the barn door framing the little hen so that it occupies the negative space and is given a highlight is a very conscientious, well thought out detail to induce clarity and balance.

Sharp ears will notice that the song switches keys about a third of the way in—after Porky’s initial chorus, the tune rises a half step from a somewhat uncertain A natural to B flat. It is incredibly subtle and not something regular listeners would likely identify, and is by no means a detractor of what is on-screen. Rather, it merely serves as yet another an interesting little footnote to chew on.

Following a pattern of Porky > gag > Porky > gag, his section of the song comes to an end through the highlight of his dog burying a bone. A bone in a jar, of course. Itself, the visual is amusing through its humanity and sentience; dogs do not have the capacity to retrieve a jar, open it, store a bone in it, close it, and bury it, etc., etc. Yet, even if it admittedly isn’t riotously hilarious, it flows well with the previous idea established of Porky storing jars in his basement. There’s a continuity to it, a justification—not just random for the sake of randomness.

A camera pan across the other side of the road is just as thoughtful, if not more. Background art is provided by Bob Holdeman, an ex-Disney artist who had already left Warner’s by the time this short was released; the pan serves as a gorgeous representative of the parallels mentioned in the introduction.

Abundance versus disarray. Porky’s farm is idyllic and cozy, with lush trees, plowed fields, and a barn tucked away in the background to indicate his property is well maintained and lived in. An apple tree in the foreground catches the audience’s eye first. Indeed, his apple harvest is bountiful. So much so that there are a number of apples lying on the ground, indicating he has a slight surplus; the product of his hare work.

Thus, it only makes sense that the neighbors across the lane are the complete opposite. Shorthand for their own apple tree is highly amusing—instead of depicting any apples on the tree as shriveled or moldy (or absent all together), they’re instead painted to be full apples that have been eaten down to their core. It doesn’t make much logical sense—unless one were to speculate that they had their own apple harvest, and couldn’t even be bothered to pick them off the trees so they just ate them from the branch—but immediately registers in the viewer’s mind as an opposite. That’s the main priority of such a first impression—establish the antithesis.

Given the decrepit appearance of their shacks, with dead trees, broken fences, discarded trash, and imposing, empty hills accounting for their “landscaping”, the juxtaposition registers incredibly well. No words need to be spoken to establish that Porky’s neighbors do not subscribe to his maxim. Instead, the painting speaks entirely for itself, and clearly at that. The symmetrical, parallel staging of both properties allows the audience to catalogue the aforementioned discrepancies with more clarity and ease.

Enter the nameless bear and his dog companion (whose appearance isn’t entirely dissimilar from Tex Avery’s first design of Willoughby in Of Fox and Hounds); if the tattered clothes, slack jawed expression and complete disregard for the audience from the bear and dog respectfully don’t convey their ineptitude, the bear’s song of “Working Can Wait” certainly makes up the difference. Lyrics spun from “Heaven Can Wait,” Blanc’s vocal performance and Maltese’s lyrics make for an end result that is just as memorable as it is funny.

It helps that the bear’s voice isn’t a part of Blanc’s stock armory of voices. Hoarse, haggard, his performance in this cartoon is one of his most effective to date—that may not apply to this particular moment, but even the novelty of hearing a voice that he hardly uses is enough. You will always know when you are hearing a character voiced by Mel Blanc. This is one of the rare exceptions that, save for certain instances, it isn’t exceedingly clear upon the first impression.

A nice detail about the bear’s chorus is the guitar in his lap—he bothers only to strum it occasionally, as though even that requires too exhaustive of an effort. Meanwhile, the dog demonstrates his own sloth by bothering only to slap a fly out of the air with his ears. No swatting, not even a display of any sort of annoyance. It’s right to sleep immediately after.

Moving forward, it makes sense that all of the other denizens of the property—a mouse lounging in a hammock, a decrepit cat, hens playing board games instead of laying eggs, cows fawning over Ferdinand the Bull—are just as complicit in the laziness as their owners. It isn’t so much a showcase of gags as it is an opportunity to establish the atmosphere, one where lethargy and laxity is prideful and aspirational. It should be noted that the dog barely having the energy to bark at the dog is directly reused from Tex Avery’s A Feud There Was from 1938.

In all, it’s a great song number that clearly establishes the premise of the film without feeling belabored or arbitrary. Motivations (or lack thereof) of the characters are made clear, as are their environments and way of life. That extends to Porky’s side as well. Subtle details enrich the performances and themes maintained (such as having the bear barely bother to strum his guitar), personality is established, and it’s a great demonstration of Blanc’s vocal versatility.

Given how oversaturated these cartoons were with their song numbers for so many years, it makes sense that the directors would want to cut back on them wherever possible. Yet, the opening two minutes of this cartoon serve as a fine return to form thanks to an equal sense of purpose and humor.

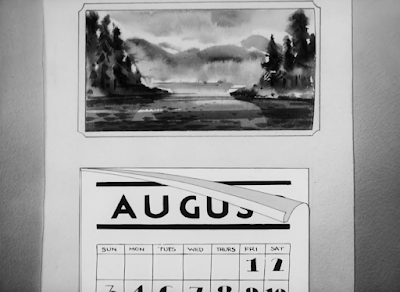

Enter a timelapse to further ease the viewer into the cartoon. Here, the traditional convention of a calendar shedding its pages is garnished with additional overlays of falling leaves and blankets of snow; it instills a permanence to the shift, indicating that the real world is impacted by these flying months and the timelapse is not just in vain.

Yet, most importantly, it plunges the viewer into the main crux of the cartoon: winter is not exceedingly kind to its slothful soldiers.

Now, we receive a parallel to a parallel—the same establishing pan of the neighboring houses is outfitted with a thick covering of snow. Going so far as to demonstrate that Porky has shoveled his lane is a great, astute detail that indicates how attentive Freleng’s direction is. No blizzard can stop Porky from his hard work.

His neighbors, of course, boast a poignant lack of that same effort.

Given all of the context and establishment leading to this point, finding the bear and his pet companion pacing around in the frigid cold comes as no surprise. Their pacing and fruitless attempts to keep warm are accompanied by a score of “Then Came the Rain”—symbolic both metaphorically of the dark times ahead and literally, given the precipitation that has exacerbated their current condition.

Dialogue is somewhat repetitive, but with a purpose. Already, Mike Maltese seems to have been settling into his rhythm as a hands on writer, as this short is nowhere near as chatty nor pedantic as the dialogue in The Cat’s Tale. There are plenty opportunities for character beats, close-up shots, visual gags, and other ambient pauses to speak for themselves. If anything, his mildly circuitous comments of “Boy, is it freezin’ in here! This is the coldest I have ever been! …Gee, is it cold!” follow the Tex Avery principle of unmistakable exposition with a comedic flair. Given his repetition, we know the cold is going to be a problem. Likewise, said repetition reads as a sort of revelation, as though he genuinely can’t believe it—that’s what happens when you spend over a minute singing about how productivity is a complete waste.

A close-up of the dog mirroring the same side slapping as a fruitless means to warm up indicates his thoughts on the matter as well.

“There must be sum’n to eat around here!” The tattered curtain rod and cobwebs within the confines of the pantry are a nice touch. Holdeman’s backgrounds almost seem antiquated—this isn’t a knock on his paintings at all, but more a commentary on how the asymmetrical, blocky wooden furniture that once served as the backdrop for nearly every cartoon has now been sanded and polished with the changing tides. These notions of regression are helpful in conveying the stubbornness and immobility of the bear and the dog, as well as merely enhancing the dilapidation of their living situation.

Peering into the cupboard yields a snarky comeback from one Mother Hubbard. Literary references—even something as simple as a nursery rhyme—are a common fixture of Maltese’s writing, and would particularly blossom at his peak.

Thus yields the greatest overreaction that could possibly stem in that moment—an overreaction that is so amusing because it’s such a painfully simple statement delivered with such honesty and pain.

Pathetic, sallow blinks from the bear serve as a launch pad for his deafening, echoing siren song of “BOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOY!!!!!!! AM I HUNGRY!”

So, the bear’s repetitive dialogue established earlier is not for naught; not just for exposition, not just for the sake of talking. This proves to be an extension of it, that same voicing of a simple desire (“Boy, is it freezing!” “Gee, is it cold!” and now “Boy, am I hungry!”). It’s as though this is the only way he knows how to talk and voice how he’s feeling—controlling the ferocity and volume of his delivery is, likewise, the only way he can stress his point. A completely barren cupboard in the dead of a blizzard warrants a much stronger reaction of “Am I hungry!”—so, instead of searching for a more succinct way to voice his concerns (even if it’s just a mere “Uh oh,”), he chooses to emphasize what he already knows.

In simpler terms: it’s funny. It’s animated funny. It’s voiced funny. It’s delivered funny. It’s funny. That same, pathetic stare as the camera fades to black is the icing on the cake—a deceptively innocent, almost sympathetic topper that feels alien against such a violent outburst. That, too, is funny.

A fade-in to the bear and his dog at a kitchen table indicates that the bear’s vocabulary is a bit more vast than the previous scene let on. Especially given that he fantasizes about indulging in a demitasse (a small cup of espresso)—very much a Maltese-ian inclusion through its sophisticated implications and sound.

Gil Turner is the chosen animator to depict their “conversation”, which is namely a one-sided monologue courtesy of the bear fantasizing about all of the meals he could go for. Any input from the dog is relegated purely to enthusiastic nods of the head, with the mention of spinach being the lone exception. One is almost surprised that the bear didn’t substitute spinach for the mention of onions instead, given the history of “hold the onions” gags in Freleng’s cartoons. In any case, his fantasies of home cooked meals (steak, potatoes, corn on the cob, strawberry shortcake…) makes the topper of the demitasse at the end all the more amusing through its incongruity.

With food on the mind, the dog suddenly gets a right notion to tear through a mountainous pile of empty tin cans. His perking up and sudden sniffing (synchronized satisfyingly through Stalling’s musical accompaniment) give the indication that there may be some extra food lying around after all; perhaps beneath that scrap pile lies the elusive demitasse.

Motivated by the idea, the bear joins in, displaying the most amount of effort exerted in this cartoon yet as he digs through the cans. He shakes one can, which proves to be empty—it’s a nice little buffer that keeps the actions and story believable. For the first can he picks up to be the one with food in it would be too perfect, too manufactured, and too favorable. After all, Porky’s song taught us that we have to earn our keep, and that evidently extends to scrounging for scraps.

Indications of food are conveyed purely through auditory cues as the bear shakes yet another can. This fabled second can has a benefit the first can did not; Treg Brown’s mischievous sound effects that are both playfully exaggerated and intrinsically tied to the action.

Sound effects mean food of some kind, and food means salvation, which is certainly the prevailing notion as the bear and his dog rush to the table. “We’re saved!” seems like a lofty proclamation over one tin can, but beggars certainly can’t be choosers.

That it takes repeated shaking of the can for anything to come out doesn’t prove to be a promising sign of sustenance. Brown’s empty, jangling sound effects really add a lot to the gravity (or lack thereof). It maintains a lightness, a playfulness that prevents the story from getting too dark or mournful. Comedy is the priority, and it can sometimes be all too easy to accidentally delve into an atmosphere that is uncomfortable. This was made at the tail end of the Depression, after all; the audience doesn’t want to be reminded of the hardships they faced. Thus, maintaining a prevailing tone of mischief is vital.

Finally, with some added shaking and finagling, the meal of reckoning spills out onto a single plate: a bean.

Speaking from a technical angle, the close-up shot of the bean that follows is not necessary. Even in the wide shot, the audience can clearly see the lone bean on the plate—it’s not as though there’s a fanciful feast obscuring the view elsewhere. Likewise, the bean itself is relatively big, again aiding with visual clarity.

However, this close-up shot is absolutely not arbitrary. It’s armed with a very noble purpose: comedy. That tight close-up shot, putting the lone bean in focus, no commentary from the characters, muted music sting as the only background noise, all of that is to make a point. It exists purely as a commentary. A commentary from Freleng, a commentary from Maltese. It’s a punchline in itself, seeking to rub the unsubstantial meal into both the viewer’s face to solidify that the bear and his dog are, in fact, not saved. It’s a very effective comedic sting.

Maltese’s brilliance as a writer manifests through the reactions of the characters. The natural impulse in this situation is to immediately go for disappointment of the characters. Perhaps even anger. Sallow, confused glances, a bloated beat as the emotional gravity settles. Tension is another possibility, with the potential to pin both characters against each other regarding who gets first dibs on the bean.

Not that those avenues aren’t amusing, but the avenue that Maltese chooses is much more intriguing, devoted, and, of course, funny. It takes more thinking and inventing to have both characters react not only favorably to their non-meal, but rapturously. Likewise, having that joy and rapture feel genuine and motivated (no matter how much of an overreaction it may be) is a whole different challenge in itself.

Nevertheless, both Maltese and Freleng rise to the challenge well. When the dog’s eagerness gets to the best of him, immediately lunging for the bean, the bear puts on a pious air that seems amusingly discordant with his character.

“Here! Where’s your manners? We should be t’ankful for all ‘dis!” The dog’s disgruntled shakes of his paw after getting slapped with the knife is a great piece of acting and a nice detail from the animator. From the elongated mouth shapes, it seems to be the work of Cal Dalton.

“Now, don’t you t’ink we should say grace?” Disingenuous conceit positively drips from the bear’s acting, serving as a great juxtaposition to the sincerity of Stalling’s chorale in the background. His relief at finding food is certainly genuine, and gratitude as well—however, the audience gets the idea that he’s never led a meal with a grace in his life. There’s a production value to it all.

A production value that both are willing to engage in, despite their starvation. Again, kudos to Maltese for going this length just for a bean. The absurdity is never once lost on the audience, as it’s the primary point of the sequence—still, it is directed to feel sincere and motivated. There isn’t a comical backing track in the background mocking the characters, no glances towards the audience from the dog or other synonymous displays of uncertainty. Freleng and Maltese trust the situation is funny and asinine in itself to be independent.

Thus, with heads bowed, hands clasped, eyes closed, their thoughtful silence offers the perfect opportunity for a mouse—the avid reader of Of Mice and Men seen earlier—to come in and steal the goods for himself. Freleng, Maltese, and Tedd Pierce would take this same gag to much greater lengths in Along Came Daffy under nearly identical circumstances; there, the mouse dribbles its prized pea like a basketball, actively weaving in and out of the threat posed by Yosemite Sam and his brother as they attempt to corner him. Of course, the mouse in that cartoon appears in basketball garb at the ready—it’s a very amusing and incredibly well timed extension with snappy timing, funny visuals, amusing intentions and solid execution.

Of course, that isn’t to say that the simplicity of this scene is bad or leaves more to be desired. Quite the opposite—the brevity in which the mouse appears and disappears is bold and surprising, and elicits a laugh with how perfect the setup is. Both the characters on screen and the audience are caught by surprise at the same time (there are no indications of the mouse eavesdropping or lurking around to telegraph the gag), making for a strong impact and justifying the bewildered reactions from the victims of the bean snatching.

Even if said reactions quickly delve into overreaction. An overreaction that manifests in defeated sobs…

…which rises in a crescendo to manic laughter…

…and careens back into desperate sobs.

No amount of description in text—whether 3 pages worth of 3 sentences, as above—will be able to succinctly capture the magic of Blanc’s performance. It’s not something you have to hear for yourself, nor see, as it’s much more than that. It’s something you must experience for yourself.

What is Mel Blanc’s best performance? Asking that question is somewhat fruitless, as there’s no way to categorize it. Pure subjectivity—how would that be qualified? What defines best? Is best important? Surely this one-off bear character isn’t important. Regardless, musings aside, it isn’t much of a stretch to say that this is certainly, as of March 29th, 1941, one of Mel Blanc’s most visceral performances to date. It’s exaggerated, it’s loud, it’s funny, but it also feels so painstakingly sincere and genuine in both the manic laughter and strangled sobbing that it evokes a real sense of concern from the audience. It’s haunting and hilarious in all of the best ways possible. If someone had never heard of Mel Blanc before and needed to understand what was so great about him, this would certainly be a snapshot to show them.

Gil Turner’s animation is considerably softer and mushier than the structure of the prior scene. Here, he animated the dog, who has his own commentary: “Say, the guy’s out of his head!”

Heavily ironic, considering that the audience feels as though they are out of their heads hearing the dog speak for the first time. He does so with staggering casualty, no introductions required—the domesticity of his voice supports such a rigid, forced sense of normalcy that is inherently funny. The implication that the dog could talk this whole time, what with his growls and noises and other acts of domesticity, is, again, very funny and understated.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if he tried to eat me!”

Neither would the audience, given that such a declaration provides the perfect opportunity for his comments to manifest. Like the suddenness of the dog’s gift of speech, the reveal of the bear with his knife and fork in hand succeeds through its diligence. No sounds of him rooting through any drawers off screen, no indication he’s searching for a weapon through a revealing close-up or even a shadow on the wall. Again, the audience is just as surprised as the dog as they experience the reveal in real time. Of course, the dog’s line tempts fate enough for the audience to expect a reveal of some kind, somewhat putting them ahead of the curb. Regardless, it elicits the intended jolt of surprise and amusement through such streamlined directing.

“No… no, don’t!” Gentility in the dog’s voice rises to a panicked climax as he grows more desperate, matching the laden footsteps of the bear as he approaches him. “It’s me! I’m your dog—“ The high pitched barks are much more akin to a man’s impersonation of a dog over the dog barking itself (which we know he is capable of when he “barks” at the cat), which is why his compulsion to prove himself is so funny—“remember!?”

Steadfast silence and a lack of discernible motion from the bear proves genuine in its unnerve. Given that his only action is to continue cornering the dog with laden, slow footsteps, bargaining doesn’t seem to be an objective in his mind. Commentary from the dog as he pleads—both to the audience and the bear—keeps the tone somewhat lighthearted, playful, but there is also a very real sense of gravity that gives an authenticity and intrigue to the conflict. It really does seem as though the dog’s days are numbered.

Their entirely one-sided “altercation” is taken outside, both to indicate the insistence of the bear and the desperation of the dog trying to make a mistake. It’s also a convenient launchpad for Freleng and Maltese to get Porky back into the picture, as it is his house that they pass amidst the dog’s begging, pleading, and threats (“I'm warning ya... you'll hang! They'll getcha for it!”).

Rather than having the characters march all the way across both properties, past the country lane, over hill and dale, a mere cross dissolve from the bear’s shack to Porky’s house communicates the same thing. Both houses are positioned identically, allowing for the dissolve to read seamlessly as the dilapidated shack seems to melt into a cozy farmhouse. It’s concise, it’s quick, it’s a way to indicate the passage of time that doesn’t seem laborious or contrived. By now, the audience understands that the bear isn’t about to let up on his almost-but-not-quite-cannibalism.

Goings on inside of Porky’s house is drastically different than those that are occurring outside. Ever the living Norman Rockwell painting, he’s just begun to carve a turkey that’s nearly as big as him. Likewise, instead of trying to eat his dog, he goes the extra step and gives him his very own spot at the table—plate, glass and all! A much more inviting, pleasurable atmosphere. (As a technical aside, Brown uses the sound of someone rubbing their hands together to accompany Porky carving into the turkey—an incredibly creative decision that works much better than it really should.)

Bear and dog take note. Very well executed with a great frankness in the timing; it speaks to Freleng’s ability to get a laugh from even the most simple of actions.

Knocks on Porky’s front door just seconds later immediately indicate their intentions—as if them rocketing off-screen and out from the frame of the window wasn’t enough of an indication.

Dick Bickenbach has the honor of animating the first true interactions between our metaphorical grasshoppers and ant. Identifiable right away through the eye blink lines he gives the characters, his acting isn’t particularly fancy—namely because it doesn’t need to be. Instead, it’s charismatic, solid, constructed, a charming visual aid to the bear’s introduction.

“Oho, pardon us!” From his demure syntax to the polite gesture of taking off his tattered hat, the audience immediately understands that his polite manners are nothing but a performance. The discrepancy between his murderous tendencies to his gentlemanly tranquility is startling and hilarious, as though a switch has been turned. Nobody would have any idea that he was planning to murder and devour his canine companion in cold blood not even fifteen seconds prior. “We’re you havin’ dinner?”

The aside of “…smells good,” that follows immediately after is delivered with perfection. Understated, subtle, it’s the only part of his spiel that is said in complete earnest. His dog mirroring the same sniffing motions is a nice touch; it makes him seem more loyal to his owner, in that he’s mimicking his actions, but more importantly distinguishes that he too is ready to get in on the action by any means necessary.

“Heh, now don’t-don’t let us bodder ya! Eh, y’see, wuh-we we’re just passin’ by an’…”

Mike Maltese’s contributions to Porky as a character are interesting. It was a character he’d get to know quite well, of course, between writing for Freleng and Chuck Jones especially. The vision of the director obviously contributes a great deal as to how the characters conduct themselves, but writers—especially ones as talented as Maltese—have the opportunity to glue everything together and see that vision through.

While it’s not as though Porky hasn’t expressed any other emotion aside from good hearted innocence or blissful oblivion, the abrasiveness of him slamming the door in the faces of his neighbor is a pretty substantial development. He’s been stubborn, he’s displayed annoyance, he’s beaten his coworkers to a pulp as a means of revenge (where that instance was likewise under the direction of Freleng), but it’s been very rare for him to display this sort of outward aggression without any sort of crescendo beforehand.

Quoting the advice of Jiminy Cricket verbatim (albeit impeded with a stutter) doesn’t do much to make his argument that much clearer, but it is an incredibly amusing character beat.

“You eh-buh-be-eh-buttered your bread, nuh-ne-nuh-ne-now sleep in it!” implies he’s wise to the sloth of his neighbors and is able to see through their act. Freleng and Maltese take sympathy towards his point of view, but, in that moment, he is specifically made to look like an ass. The bear can still be heard talking through the other end of the door; Porky’s interruption seems more rude in the process, but it also allows the audience to laugh at the steadfast determination of the bear to get a meal.

Porky catching wind of the “LOVE THY NEIGHBOR” maxim posted on the wall is one of my favorite character beats for him, as is the entirety of this scene. It is incredibly well directed and supported through the wryness in Freleng’s directorial tone: similar to the camera cutting to a close-up shot of the singular bean on the plate, the camera makes a somewhat shaky truck-in to the sign on the wall. It too is easily readable from the wide shot and doesn’t require that added close-up for clarity, but clarity is not its main intent—that camera move seeks to chide Porky on his militance, to wag a finger in his face.

It succeeds. Porky can be stubborn and convicted, a trait that would really reach its zenith throughout the ‘40s as other assets of his personality were explored, but he still has a good heart. So much so that his need to do good prevails, even if begrudgingly so. It’s a very charming little aside that’s as humorous as it is telling. Odd as it may seem to say, given that the cartoon is so inventively directed and raucous in other areas, this is one of my favorite parts of the cartoon.

Particularly through Porky’s “correction” of his previous behavior; he doesn’t apologize, but merely opens the door in restrained, somewhat contemptuous silence. Thus enables the bear to recite his spiel from the very beginning, word for word (sans the “smells good” aside). It’s as though he’s completely oblivious to have been interrupted, and what that implies. Yet, it seems more accurate to surmise that he simply doesn’t care. Whichever is the case, the decision to repeat the entire introduction from the top as though nothing happened is hilarious and executed brilliantly. Freleng’s wry commentary and knack for playing things straight is especially poignant in this moment.

Likewise, Porky’s “invitation” is just as amusing through how positively disingenuous it sounds. Again, Blanc is perfectly directed in his vocals—his tone is low, restrained, steely, as though it’s taking every fiber of Porky’s being to not lose it in that moment.

“Well, uh… wih-wee-won’t you fellas come in an’ have… dinner with us…”

Freleng’s behavioral and comedic timing is in top form as the fellas in question disappear off screen in a flash. They’re in the door the absolute millisecond they’ve been given permission.

So much so that Porky continues preaching to an empty porch (“…Eh-weh-we-we have plenty to.. go around…”) and has to manually register that his guests have disappeared.

That’s because they’ve already sat themselves down at the table and have begun stuffing their faces. We only see the bear gorging himself, but the implication is that the dog is doing the same on the other end of the screen. In typical Freleng fashion, the bear’s chomps and slurps are timed to the music—a syncopated rhythm of “Heaven Can Wait” that indicates a sort of abrasiveness through its lack of convention.

Another cross dissolve seeks to wrap up the point that the bear’s a glutton, as well as indicate the passage of time; we don’t need to bear witness to a 5 minute clip of the bear stuffing his face. Empty plates, skinned corn cobs and barren turkey bones, a swollen stomach and the inherent haughtiness of him picking his teeth all speak for themselves. Eye blink lines again distinguish as Bickenbach’s hand.

“Yessir, Porky. I certainly learned my lesson.” The audience wonders how Porky feels about all of this—standing off screen with the same contemptuous glower and hands on his hips, no doubt. “You won’t catch me cold an’ hungry next winter. No sir!”

Thus, the powers at be attempt to put him to the test; chirps of a bird off-screen and the ever telltale music cue of “Spring Song” indicate that the woes of the weather have come to an end. Ditto with a pan of the camera illustrating that same point. Suddenness of the new season is absolutely brilliant; the calendar read January earlier in the cartoon, and all of the events that unfold thereafter are implied to be self contained within that same day. So, to have some of the snow melt, the trees to bud, and the birds to sing within the span it takes for the bear to finish his meal is not only asinine, but the point of the gag. It’s not supposed to make any sense at all. It’s convenience for the sake of convenience. Contrivance for the sake of contrivance. Freleng embraces it with pride.

Snow does still litter the ground as the bear rushes back home to keep the premise somewhat down to earth—absurdly convenient as the shift between seasons is meant to be, to have every single trace of snow gone would be a bit much. Likewise, such is intended to enunciate the bear’s eagerness towards the very first sign of spring, even if said sign unfolds while snow is still on the ground.

Rejuvenated, inspired, humbled, and blessed by his near death experience, the bear and his faithful companion (who rushed to his side after a slight delay) prepare for a new year of change and bounty the best way they know how:

Resuming their chorus about how working is for chumps. Working means nothing if you can take advantage of your neighbors and assert yourselves as happy leeches. It should be noticed that the chorus this time around is three times as fast, and the bear is playing his guitar properly—in the moment, he has enough energy to put it towards those things. See, he is a new man! He isn’t a complete cretin! He’s able to play the guitar, whereas earlier he could barely strum it!

Thus, the iris closes as the dog now contributes to the chorus over the traitorous mouse from before: working can wait.

Porky’s Bear Facts, for all its humor, is a cartoon with a very cynical message and boasts politics that I myself am not particularly aligned with. In spite of that, it is a cartoon that I love very shamelessly and take legitimate offense that it isn’t more talked about. The term “masterpiece” has connotations of notoriety, importance, recognition—this short is not one that is particularly well-known, being that it’s relatively self contained, but I very much would put it as one of Freleng’s strongest cartoons at this point in his career.

When thinking of this cartoon, the first thing that comes to my mind (outside of the brilliance of Blanc’s deliveries as the bear sobs and laughs hysterically, or Porky’s endearing decision to quote Pinnochio of all things for his argument) are the parallels. Parallels between Porky’s tidy farmhouse and the bear’s ramshackle abode. Parallels with how the camera dissolves from the bear’s house to Porky’s as the bear is pursuing the dog. Parallels between the bear’s hungry, contended expression and the dog’s fear versus their enticement as they catch wind of Porky’s sumptuous meal. It is a cartoon of contrasts—the discrepancies are exceedingly clear, coherent, allowing the audience to follow the story and motives of the characters clearly. Yet, such clear indication of these antitheses don’t feel belittling or insulting through their clarity. Freleng manages to turn this sort of symmetry into a rhythm, a natural rhythm that keeps the cartoon flowing and the audience engaged.

Moreover, his ability to let things lie as they are is incredibly appreciated. He doesn’t need to imply a long winded explanation as to why the viewer should laugh at something. He allows shots—the close-up of the bean, the truck-in of the “love thy neighbor” sign—to speak for themselves. There is a slight commentary behind them in the decision to give that spotlight—a prevailing sense of dry irony—but it never feels forced not explicit. The audience is trusted to get the joke. It should be mentioned that the jokes actually being helpful speaks a great deal to his success.

It feels asynchronous to label a cartoon with such a cynical message (if people haven’t earned their keep, then they’re not worth helping at all seeing as they’ll only take advantage of your hospitality and will be complicit in any potential sloth that arises thereafter, running the risk of repeating the entire ordeal all over again, so why bother?) as a “comfort cartoon”, but this is indeed a short that always puts a smile on my face. Mel Blanc really earns his role as a vocal superstar with his versatility and ferocity. Maltese’s writing is very funny, whether it be something like the bear repeating entire conversations over again or the mere inclusion of a funny sounding word like “demitasse”. Porky’s begrudging nature is novel and amusing, if not somewhat endearing. Freleng’s directing is extremely present and motivated. Brown’s sound effects are playful, inventive and fitting, and Stalling’s music score is a joy to listen to, whether as a backing track of a main song number.

Outside of the general message, it’s a cartoon that I myself cannot find any major qualms with and, again, am slighted that it isn’t discussed more. Hopefully, by reading this review and inspiring readers to snoop out the short for themselves, that will change.

I wonderful post on an often-ignored cartoon short. I'm glad to have found your blog, cuz this is excellent content. I know we are a long way off from the 1960s, but I really do wonder what sort of commentary you will have for the DePatie-Freleng/Format Films Era or the Seven Arts Era.

ReplyDelete