Release Date: March 8th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Joe Glow)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

The first of a handful of black and white cartoons directed by Chuck Jones, these would be some of the only non-Technicolor shorts of his entire career. Likewise, this very short would—with the exception of some Private SNAFU shorts—would be the only B&W Jones cartoon not to feature Porky in some way. Certainly much novelty to be had in such a fleeting snapshot.

Comparatively cheaper as the black and white shorts may be, Jones’ production values certainly didn’t take a beating. If anything, the shift in color (or lack thereof) presented new artistic ambitions to work around—how to make values pop, how to ensure actions and backgrounds are clear, where to place the emphasis on lighting.

In a way, Joe Glow, the Firefly is essentially about lighting, being a firefly and all. We follow the antics of the eponymous lightning bug, who explores the tent and even body of a sleeping man.

But first, a note; as hinted in the last review of The Cat’s Tale, this short touts a rather unique opening music cue. Whereas Tale’s variation in the ending cue was subtle, this arrangement is much more noticeably bombastic. Key changes, instruments trilling, elaborate layers—it’s most comparable to “The Merry Go Round Broke Down” as performed by a marching band. This explosion of stylization is unique to only the opening—the ending accompaniment to Porky’s “that’s all, folks!” remains the same.

Why the change? That remains relatively unknown. The next Looney Tune short, Porky’s Bear Facts, does herald new opening music that would be used all the way through 1945–perhaps the experimentation in this short and the succeeding entry indicate a restlessness and desire to change the arrangement. Or, perhaps more accurately: they just felt like it.

With that, we delve directly into our cartoon. The establishing shot is pretty indicative of the antics that follow: mellow, picturesque, and—to account for the flute glissando accompanying the firefly looping around in the air—playful. Depicting the firefly as a glowing speck is a nice shorthand rooted in realism; the softness of the light cements as such, more believable of the real life counterpart than what a mere opaque spot of paint would allow.

Its movements are very nicely timed and spaced. Such weightlessness as the firefly loops, circles and sways through the air and into the tent ironically is rooted in weight—where best to place the easing in and out of the action. Very rhythmic and flighty.

Through the firefly’s intrusion into the tent, the viewer gets their first glimpse of the human: his construction is incredibly solid and well sculpted, which proves to be rather handy given his purpose as an interactive backdrop. To have a firefly land, explore, climb, slip, and trek on a human whose design and features are mushy and unanchored would make for a rather tedious viewing experience. Thankfully, Jones’ art direction has evolved past such concerns, and he’s able to execute his mission well.

Elevation of said art direction is present even in a close-up of the firefly marching through the man’s hair. Already, textures of the hair and textures of his skin are exceedingly visible—quite the feat to pull off, especially in such limited lighting.

Jones fakes out the audience at the last second with the source of the firefly’s light. Whereas most cartoons caricature the light as, say, a lightbulb attached to the body of the firefly, Jones’ adaptation doesn’t have a light on his body at all. Instead, a lantern is revealed to be the light source; the firefly thusly looks indistinguishable from every other cartoon ant of fly. It’s certainly a unique spin, and one that seems to humanize the bug more than anything. Why does he have this lantern? Where did he get it?

The same could be asked of his hat. Such an accessory hints at a backstory of sorts—the viewer is left wondering what his occupation is, how he got it, etcetera, etcetera. Curiosity is piqued. Thus, engagement with the short is thereby strengthened. It’s obvious the firefly has some sort of mission—it’s our duty as the audience to stick around and see what that mission is.

An up shot of the firefly looking over the man’s face seeks to establish a warped sense of scale; it isn’t the firefly who is small, but the man who is big. Perspective is secure, strengthening the illusion; the background consisting primarily of an empty color card almost seems to exaggerate the depth further. It’s as though the human is the only thing the firefly has in this void, and even that is slim with the risk of slipping.

And, of course, that is exactly what happens. This in itself offers some great opportunities to asset the interactivity of the environments—an important task, given the immobility of the man.

Indeed, objects such as his nose and curves of his cheeks provide the illusion of dimension and depth as the firefly’s cel dips in and out of the curves. It establishes perspective, which establishes permanence. The man isn’t just a backdrop—to the firefly, he’s also a liability.

Much of the short’s premise seems to lend itself to similar themes established in Sniffles Takes a Trip. While both feature the main characters staring into the eyes of the very mammal their standing on, thereby spurring a startled take, that isn’t the main similarity—rather, the themes of exploration and warping perspective to evoke sympathy for the pint-sized protagonist. Trip did a great job of establishing this, doing its best to make both Sniffles feel small and the environments tall, but the short wasn’t exclusively dedicated to that theme. This one is. With that experience of the former under his belt, Jones could then freely manipulate said premise and learn how to make it stronger and more interactive, rather than focusing on how to implement it at all.

So, while it would be easier for the firefly to scramble off screen and default to a new location, a more immersive alternative is heralded by the insect hiding behind the man’s nose. Background paintings are saved that way, the shots feel more coherent with such a pause, and having the firefly hide and poke his head out from behind the nose again cements the permanence and interactiveness that the man poses.

Perspective does momentarily falter in its solidity through a close-up of the firefly sitting on the man’s cheek; that can be partially owed to the “background” being a flat cel drawing. The opaque paint indicates that this cheek and mouth are going to move, which provides to be exactly the case. Regardless, a dissonance intercepts the firefly and man in their conflicting perspectives. Either the man’s face should be drawn at a more diagonal up angle to support the bug’s feet dangling over his cheeks, or the firefly should be depicted at a top-down view to match the layout of the man’s face.

Said “smile gag” stretches on more than is warranted, but proves to be an effective change in tone. As the man’s face twitches, constricts and moves to shake the firefly off, the music grows hurried to match the crescendo in action as the bug is forcibly tossed about. A subconscious reflex in a human proves to be tumultuous for such a little bug; all a part of Jones’ intent to humanize the little guy and make him seem more sympathetic. It’s a deceptively hard world out there for fireflies.

Similar visual philosophies apply to the bug now getting tossed around from the man’s snoring. Here, the gag doesn’t work as convincingly as it could because the information is primarily conveyed through sound effects and the animation of the firefly. That in itself is fine, but this scene could have benefitted from some animation on the man’s face to cement the push and pull of the inhales and exhales. Instead, it comes off as visually awkward and misguided, lacking a strong sense of cohesiveness or intent.

Nevertheless, the firefly pursues other endeavors as he’s thrown onto the man’s belly. One particular highlight is his venture beneath the man’s hand; albeit somewhat dim, light is noticeably cast between each separation of the finger as he treks along. While the depiction of the light could stand to be a bit less transparent, the black and white color scheme of the cartoon is certainly handy. Differences between black and white values are much more noticeable than what color would have potentially allowed—through such a limited palette, light is the primary focus over mixing and complimenting color.

More adventuring prompts one of the most inspired visuals of the film: the firefly hikes up the man’s watch strap like a ladder, and grows surprised to find himself standing on top of the ticking glass. Thus, an immersive, striking under shot of the watch ensues. Here, the audience looks up at the firefly through the glass, second hand cohesively marking the divide, rather than the alternative—structure and perspective of the environments are given a priority over character. While the audience isn’t seeing the watch through the bug’s eyes, the firefly’s sense of wonderment is stronger through such unconventional staging and amounts to the same effect. We don’t need to see everything strictly from his point of view to get the same inquisitiveness and awe.

Instead, character beats are given their own unique highlight through much more static staging. Static staging that places emphasis on character rather than environment. In this case, a dubious, cross eyed shrug that manages to communicate so much through so little; this little fella has no concern for such elaborate human trivialities.

Mr. Glow soon finds himself on a fingernail. To indicate a difference in texture between skin and nail, opaque lines of white are applied to the nail in order to give it a glossy, slippery sheen. Thus, the firefly struggling to maintain his balance on the slippery nail is justified visually. It’s a bit of a stretch, given that regular, unmanicured nails aren’t that glossy, but is nevertheless a clever utilization of the material. Stalling’s flighty musical accompaniment matches the action nicely.

There arrives a somewhat belabored and arbitrary bit of the firefly getting caught on the nail; his feet are lodged under the ridge, hooking him as he attempts to fly off. Here, the bit seeks to capitalize on some more character beats for the firefly rather than establish the obstacle posed by the nail; a beat as the firefly awkwardly disentangles himself, bashfully aware of his audience, is pure Chuck Jones indulgence. A lack of a mouth on the bug certainly doesn’t impede the clarity of his emotions.

A flashlight captures his attention next. Character is again a priority with this particular tangent—not regarding the firefly, but the man. Landing on the flashlight’s button predictably turns it on, which rouses the human. Lighting effects are particularly nice on his skin, with shadows dotting various creases and folds that seem meticulous to have indicated. Likewise, the contemptuous, drowsy squint on his face feels remarkably human and natural for all of its caricature; it captures the sensation of being blinded by light well.

But, like everything else in the cartoon, it’s but a mere footnote in the firefly’s exploration. As soon as the firefly takes off, the light is extinguished. So is the man’s consciousness. A shooting error somewhat blocks the impact of his going back to sleep, as a frame of his eyes still halfway open accidentally pops into view as the last held frame; the visual is somewhat disconcerting, but the intent remains clear.

Having exhausted all avenues of exploring the man’s body without growing more tedious, Chuck Jones and writer Rich Hogan fill the next two minutes with gags relating to food… such as the firefly marching directly onto some saltine crackers.

Labeling of the “CRACKERS” box in the background proves to be a clever backdrop; the crunching sound, the salt, and indented, puffy texture provide sufficient context, but that extra nudge adds a safety net of clarity that doesn’t feel too imposing or obvious of a clue.

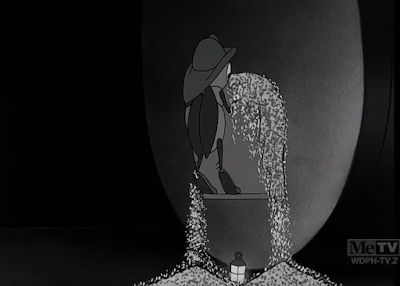

Implication of the crackers allows Jones’ animators to flex their effects animation skills, which are certainly tested. One step on a weak spot has the firefly accidentally sinking into the depths of the cracker, which prompts a trail of crumbs. Said trail grows in size as the firefly takes off in a frightened hurry—all of the meticulously inked specks that fly onto the screen seems like a major headache to keep track of from all departments: animating, inking, camera shooting. The effect looks great on screen, as there is minimal flashing . All pieces seem to fly where they should.

Effects animation isn’t limited to just meticulously inked specks. Seeking refuge in a block of swiss cheese encourages beams of light to pool from each hole, stemming from the bug’s lantern. Moving perspective of the light elevates the visual to another level—it would be too easy to just have the lights remain in the same, static position. Here, all of the beams move in varying perspective, shooting out of the holes at different times. This, in conjunction with the rolling camera pan, makes for a very rich outcome that scratches the itch for novelty but remains comparatively sophisticated.

Investigating a canister of salt ushers in the flashing issues that the cracked trail managed to avoid; thankfully, it’s only on the close-up of the firefly poking his head out of the mound. It gets a pass, as the pile of salt on his head is continuously draining (not to mention the burden of multiple paint hues conflicting at once), but does seem to be handled somewhat looser than the cracker scene.

Granted, that’s all an incredibly tiny nitpick. The visual effect of the salt pouring is stunning and convincing—even down to the weight of the metal lid sliding open. Airbrush is lightly applied to indicate waves of dust cascading after the initial burst subsides, demonstrating the lengths Jones and his animators would go to pursue the most minute of details. One hopes the inkers who had to color this sequence were compensated nicely (unlikely as that may be.)

It is somewhat telling that an exploration of a pepper shaker doesn’t receive the same treatment. Nor does it need to—the novelty of the grains was established fully with the previous anecdote. To reprise the same bit with pepper would cause the pace to drag, the novelty to be lost, and multiple cases of carpel tunnel across departments.

Instead, much of the information is communicated off-screen; firefly crawls into pepper shaker, camera follows the presumed movements of the firefly, a sneeze can be heard winding up within the confines of the aluminum shaker, which is soon explained through the explosion of the cap rocketing at the camera in perspective. All staged and thought out very clearly.

Likewise, the location of the firefly is only revealed after a series of shots to maintain any suspense possible. He resides in the tin cap currently catapulting into a bottle of ketchup, which is nearly sent toppling over the edge of the table. Cutting from a plethora of dry brush trails on the cap to none at all does spark a minor jump between shots, slightly hampering consistency, but the flow of ideas is nevertheless clear. Timing of the cap landing on the table is, likewise, very well executed and smooth, construction and perspective maintaining solidity as it continually flips over itself.

Little time can be spared ogling at the physics of the cap. Rather, Jones and company have more elaborate details to pursue—that manifests in a ball of twine that is soon converted into a lasso. Depicting the twine in opaque cel paint (as opposed to a painted close-up) gives the ball a sharper, more concrete texture—the wiry thinness of the string is much more tangible than the innate softness of a painting.

Yet, most importantly, it’s functional; the transition to the ball turning into a whirlwind of thread as both ketchup and firefly are sent toppling over the edge of the table is much more smooth than any jump between paintings.

Thankfully, a kitchen knife conveniently wedged into the table offers support for both the bottle and its pursuer. Narrowly avoiding disaster, the firefly uses the knife as a “base” for the string, tying a knot to keep the bottle suspended. Of course, it makes no logical sense for the knife to be wedged into the table like that (unless the camper in question happened to have some aggressive tendencies with his handling of kitchen utensils.) However, it reads clearly and serves the purpose of the action. That’s all that can be asked.

A staggering overhead shot of the bottle dangling established just how narrow the brush with destruction was. In spite of the scale being warped throughout the cartoon, the string does come off as somewhat too big—it certainly reads as a bulky rope instead. Regardless, the rope approach reads more clearly to the eye, and is more feasible in justifying how the bottle remains suspended. Having the layout look over and down rather than just straight on down encourages the dizzying disorientation so desired; outside of the minor size inconsistency with the string, it’s a gorgeously rendered painting that capitalizes on so many of the themes in this short: small and large.

That proves to be enough excitement for one evening—after retrieving his lantern from the depths of the pepper top, Joe Glow heads along on his merry way. Finality in the story takes precedence over any last minute visual grandiosity. Had this been earlier on in the film, the pepper shaker top very likely would have been used as an avenue to filter the beams of light cast from the lantern. No such event happens, indicating a sort of closure that is hinted through the nonchalance of the firefly’s movements and the plucky, resolved music score.

However, there is one last bit of unfinished business. We end our cartoon on a book-end, reusing the same layouts of both the tent’s interior and exterior. As the firefly approaches the man, his features are more defined than what the opening parallel heralded. We’ve spent the past six minutes getting acquainted with our protagonist—he doesn’t need to hide under the anonymity of a glowing speck any longer.

That in itself is coyly teased through the ear shattering “GOOD NIGHT!” yelled by the firefly into the man’s ear. With six minutes under our belt, the formalities of pantomime no longer apply—we’ve now been acquainted enough to access the privilege of the firefly’s voice. A gift to us all.

Admittedly, Joe Glow, the Firefly is one of Jones’ emptier efforts. That in itself isn’t synonymous with a lack of quality; quite the opposite. Rather, it’s a fancifully decorated presentation of nothing.

Thankfully, such a deduction is easier to make when the short isn’t exactly trying to be much of anything. Jones and Hogan approach these gags exactly as they are: vignettes, rather than concrete story points. The purpose of this short is not to thrill the audience with complex character dynamics of a heart pounding story. Rather, it seeks to immerse and explore. Ambience is at the forefront. Placing the audience in the shoes of the firefly and being mystified by the warped sense of scale and perspective. Being able to see the novelty of the mundane through someone—or something—else’s eyes.

It would be dishonest to say this is an immensely interesting cartoon, but it’s clearly one that is approached with lots of meticulousness and care in the art direction. Inking and tracking all of the little cracker and salt particles alone is enough to justify this, but the background paintings, the lighting, and layouts are likewise indicative of such. While it doesn’t present much, what is presented is done so tightly. It’s difficult to imagine this cartoon having the same effect if it were released in 1939–that applies to both Art Loomer’s muddy backgrounds and the growing experience of the animators. Growing experience of Jones’ directing as well.

This short is best viewed as an indulgence. Indulgence in art direction, in pantomime acting, in ambience, in minor character beats. It is unmistakably a cartoon directed by Chuck Jones. While it may have a tendency to be plodding at times, there’s nobody else who could have pulled it off as well as he did with the same intent. It’s a very beautiful and very earnest way to spend six and a half minutes.

No comments:

Post a Comment