Release Date: March 1st, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Herman Cohen

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Mouse, Cat)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Adjusting into his newfound role as a writer, Mike Maltese’s credit takes up two of the past three cartoons in the release order. While release order often differed from the production order, the fact that he’s so quick to return at all--rather than nurse a hefty gap--seems to hint towards his proficiency as a writer. That is, his hand and his mind was wanted.

Indeed, he’s already been between units; The Cat’s Tale marks the first of many collaborations between himself and Friz Freleng. Both would collaborate frequently throughout the ‘40s (often with Tedd Pierce’s input as well), and it was with Maltese that Freleng concocted one of his most iconic characters: Yosemite Sam.

Of course, this technically isn’t the first time they’ve worked together. One would be remiss to neglect mentioning Maltese’s memorable role as the security guard in You Ought to Be in Pictures. While Freleng wasn’t necessarily as perfect as a match for Maltese as Chuck Jones was (who is?), they wrote plenty of funny cartoons with a plethora of wit, and this one is no exception.

Rather than serving as another chase cartoon, The Cat’s Tale offers a more philosophical look at what exactly makes a chase cartoon. That is, who decides the hierarchy and why? Why do cats chase mice? Why do dogs chase cats? Why does this have to be the natural order? Those are the exact questions a plucky little mouse asks himself as he attempts to get the cat to disrupt the chase chain from the top down. Even if the cat is willing, the dog who he must reason with proves to be a different case.

Seeing as the cartoon’s intent is to partially question and subvert chase dynamics rather than entertain them, it makes sense that the cartoon immediately opens on the action. No exposition of any kind, no indication as to what set the cat off and made him pursue the mouse. In a way, the cold open reinforces the driving story point: there doesn’t need to be an explanation. Cats chase mice. Even by 1941, the cat and mouse cartoon was old news. The audience doesn’t need to be coddled nor spoon-fed the action.

And action, there is. Animation of the two running around is initially crude; a take from the mouse as he hides on the chair appears particularly belabored and glacial, and the movement doesn’t seem to possess any sort of tangible weight to it. Just aimless, drone-like pursuit that, again, arguably supports the intent of the film. That the drawings themselves are so small and shot at a distance doesn’t help with the clarity of the clean up work.

Regardless, the pacing does pick up as drawings are soon shot on ones rather than twos. Holding it on twos seems to freeze the action—it’s not exactly clear why the change occurs, whether it was the intent of the animator or an issue with shooting the footage, but tactility and purpose behind the movements become more clear after the switch to ones.

All of that nitpicking quickly becomes futile as the chase is lead through the house. Ever economical, Freleng obscures much of the action behind various walls and pieces of furniture, informing action through the direction of the camera and the sound of glass shattering instead. Such a maneuver not only saves a quick buck or two, but also encourages depth and dimension within the environments of the house.

Sure enough, the two foes traveling under, over and around the furniture instills solidity. Walls, beds, cabinets and chairs aren’t there to occupy space and give the illusion of a home; they are the home. Having the animals physically interact with the environments on screen cements a certain gravity and realism—the house isn’t just a backdrop for their antics. If anything, it proves an obstacle.

As all cat and mouse chases seem to do, the cat finds himself forcibly shut out from a mouse hole as his dinner seeks cover. A loud, echoing crash as he folds into the wall is the most notable auditory takeaway; yet, Freleng, ever conspicuous about his musical timing, indicates an additional tap of the cymbal right as the cat flops onto the floor. The cymbal is relatively quiet—a hiss rather than an echoing reverberation of brass—which makes its viewer registration seem subliminal. Yet, such subtlety nevertheless furthers a certain weight to the fall, giving an extra gut punch that allows the animation to read more clearly and perhaps even more sympathetic. Antagonistic as the cat may be, it doesn’t look like a pleasant spill for anyone.

Dick Bickenbach proves to be the short’s exposition superstar, if there is such a thing—the following two minutes and fourteen seconds are all his handiwork. Roughly a third of the cartoon, and a third of the cartoon that is gorgeously animated.

Freleng’s casting of Bickenbach for such a lengthy section is wise. Ever versatile, as these reviews have expressed, he could cover a wide range of emotions, contexts and needs—wild takes, frenzied animation, or subtle, personalized acting and character beats. Much of the second is called upon for this segment, but there are little flourishes of head shakes, surprised takes, and other spirited pieces of acting that juxtapose nicely against the more down to earth conversation.

That is something this short has no shortage of: conversation. After all, one of Maltese’s greatest strengths was his dialogue. It doesn’t seem outrageous to call this short one of the most dialogue heavy on record—at least for Warner’s. All of Bickenbach’s two and a quarter minutes are completely dominated through dialogue; dialogue of the mouse haughtily monologuing to himself, and dialogue of his confrontation with the cat. Thanks to Bickenbach’s energetic animation, Maltese’s witty premise, and, of course, Blanc’s motivated deliveries, this concentration of chattiness feels earned and intentional rather than bloated or aimless.

“There he goes again! The same old thing!“ Belabored breaths pepper the nasal monologue of the mouse as he rants and raves, gesturing and waving his arms. The gulp that separates his delivery of “Every time I put my foot out of the hole… he chases me,” is particularly impressive in how natural of an impulse it feels and sounds. His winded state is sincere, the chase taking a genuine toll on him; he does sound like someone struggling to outrun the limitations of their speech in the moment rather than an actor directed to take a quick pause. Such a pause indicates vulnerability, which thereby induces sympathy.

His monologuing amounts to a solution: in his words, a showdown—a phrase that sounds much more bombastic in his mind than “confrontation.”

“What am I? A man or a mouse?”

The quick pause as he has to mull it over is well timed. His steely, determined demeanor falters for just a moment, the wide eyed and perked ears appearing decidedly mouse-like. It’s as though he has to carefully parse out his words. He is a man, right? Make sure to say the right “m” word.

“Why’m a man!” is the correct response. Again, nice acting with the puffed out chest and slamming of the fist against it—his idea of what it means to be masculine.

Stalling’s equally triumphant music score is a nice conviction to the material. In spite of all of the mouse’s monologuing and bragging, the audience isn’t entirely convinced of his status as a bonafide man. Rather than discredit what little reputability he has, Stalling’s music cues offer to entertain his fantasy and illustrate what the audience imagines he hears. Brass, staccato music stings that crescendo with each burst, a laden drum cushioning each blow. Such gives it that “call to arms” feel so represented in the mouse’s acting.

Both cat and mouse seem to be astonished at the confrontation. Upon seeing the mouse march out of his hole, the cat seems visibly confused—his expression is much more domestic through its vacancy than the snarling grimaces he bore moments ago. Likewise, upon making eye contact with the cat, the mouse buckles beneath a brief startled take. Pompous as he may be, he’s still out of his comfort zone and taking a rather considerable risk.

“Now take it easy,” he orders upon seeing the cat bristle and bare his fangs. Obviously, the cat was not expecting such contrarianism, and his obedience to such orders proves to be mildly amusing. Any other cat would have taken such condescension and conceit as both a threat and annoyance, using that as a springboard to justify the mouse being their next meal. That this cat takes the time to listen—much less feel actively threatened—indicates that he himself may not be as imposing as he lets on. “I wanna talk to you.”

The following “I SAID SIT DOWN!” is 100% an intimidation tactic as the mouse rides the waves of his ego trip; a pause has barely any room to ruminate between the two commands. As a consequence, the cat makes a production out of thrusting his butt onto the ground; an audible “THUD!” conveys forceful obedience.

Mouse explains that he’s tired of the “chasing business”, and how it’s been taking a mental toll on him.

“Look! I-I’m just a bundle a’ nerves!” He makes as much of a production out of his shaking hand as he does his embrace of masculinity or berating of the cat. Viewers in the audience get the sense that his shakiness is manufactured, controlled; the chasing has obviously taken enough of a toll to lead him to such a point of egotism, but the production values within all seem to be a part of his plan. For more authentic shakes and nerves, one might look to the bewildered, startled head shakes on the cat as his brain struggles to process the pompousness forcibly thrown on his plate.

Maltese’s hand is exceedingly present as the mouse interprets the feud as a social commentary—turning it into a racism metaphor of sorts is that kind of elevation and “sophistication” he so brought to the table.

“That’s the trouble with this country.” As the mouse marches into his mouse hole, his voice is suddenly shrouded in an aluminum din. Such effectively communicates further depth in the surroundings, giving the house dimension and a real sense of immersion. His pacing is a natural acting decision, restlessness strongly conveyed; and, again, the benefit of not having to animate the entire spiel was likely appreciated. “It’s overrun with cats!”

Now, the mouse sticks his head out of the hole to cement his next point. “I’ve got just as much right here as you have!"

Back into his hole as he gives a concession—it’s as though his “I dunno. Maybe I’m wrong,” is too embarrassing of an omission for him to admit to the cat’s face. “Maybe I’m just old fashioned.”

Maintaining the organicism of his acting (and to differentiate beyond aimless pacing), there comes an incredibly well animated and motivated bit of the mouse picking up a speck of something on the ground, examining it, and dismissively throwing it away. That speck had been there for the past 20 seconds or so, but is obviously nothing the audience was paying attention to. Such a maneuver from the mouse coyly calls attention to it, but, most importantly, renders him keenly aware of his surroundings and the most minute details that even the audience doesn’t notice. It’s a powerfully inventive and novel piece of character acting that gives the mouse a genuine depth and dimension to his character.

Given the threat he poses to the mouse (and the fervor of his aggression witnessed a minute before), the audience wouldn’t expect the cat’s voice to sound as amusingly domestic as it does. Indeed, his Jimmy Stewart adjacent vocals are congenial, awkward, and illustrate him to be a bite of a rube. Such is asserted through his vacant explanation of “Why… why, cats have always chased mice!”

Predictably, the mouse does not take kindly to this answer. His response is much more acerbic, directly mocking his words; Mel Blanc flexes his vocal talents particularly well between both characters, as they sound completely independent of each other. Thus, he’s able to tap into a different range of emotions for both—pushy, aggrieved conceit from the mouse and bumbling obedience from the cat.

“Well… uh... dogs have always chased cats,” is a particularly well acted line. A very human flimsiness in the delivery, as though the cat understands his argument is nonexistent but truly does not know anything else. Dogs chase cats. Cats chase mice. It’s all he knows and lives for.

Of course, the mice handles this new development even more poorly than the first answer. So much so that he brings the audience into it; the “How d’ya like that?” is very well regarded through Bickenbach’s animation. To match his vocal and emotional acidity, the mouse’s movements are snappy, quick, broad. Meanwhile, the cat barely regards the audience—he sees them, but doesn’t sees to understand that they’re witnessing his public humiliation. It’s a much more effective gesture than if he hadn’t glanced to them at all. Very well timed, very well acted.

Having reached his breaking point, the mouse threatens him with strangled words. The “…fool,” that follows his plethora of climaxing “you… you… you…!”s is very obviously a placeholder for a much more incriminating insult, but that very well may have been a coincidence. Looking closely, the mouse’s jaw moves twice, but only the single syllabic word of “…fool” comes out, whose pause seems a hair longer than necessary. There’s a possibility that his insult was more incriminating—even if it was something simple like “damn fool.” Nevertheless, the hesitation still works with the intended comedic effect.

After more back and forth, the mouse demands the cat stick up for himself and tackle the source of the hierarchy: go up to the dog and demand he stop chasing him. The cat agrees—not because it’s an issue he’s passionate about, but because the mouse keeps insulting his pride and insinuating he’s “yellow”. Lengthy as the back and forth is, it’s very well acted from both parties and Bickenbach’s animation continues to support it well. Staging is relatively routine, the occasional wide shot peppered between close-ups of both characters, but it allows for the eventual transition that follows to seem like a much greater breath of fresh air.

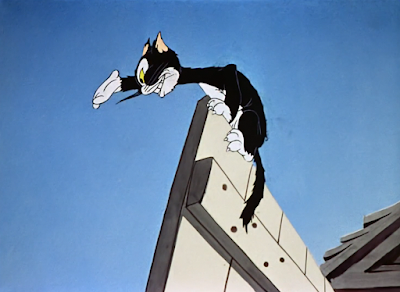

Indeed, the cat goes out to prove himself, indicated through his laden, aggressive march through the yard. Amusingly, the length of his footsteps—for all their aggression—are incredibly short, his strides nonexistent. It’s almost as though he’s stalling for time; one doesn’t get the idea that he was that convinced by the mouse’s spiel.

Indeed, he was not. In a matter of moments, his stomping turns into a stumble, which bridges the gap between a halting pace. That little hop between stomp and stop adds a substantial piece of organicism to his acting—it conveys a loss of control of his movements, which indicates vulnerability. Even against a mouse with an ego problem, he’s the submissive one. What does that make him against a vicious dog?

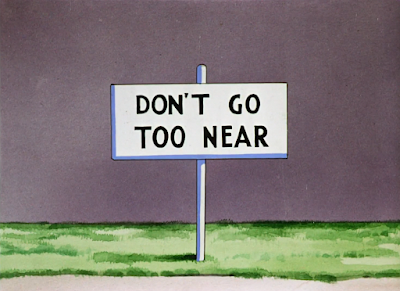

His faltering movements aren’t necessarily out of a weakening constitution. Instead, they serve as a response to the coming barrage of signs—something Mike Maltese would become well acquainted with in his time with Chuck Jones. It could even be argued that this gag here is tangentially related to some of the most memorable sign gags in the Looney Tunes repertoire; the rhyming scheme of the carefully arranged signs, one after the other, introduced in increments and each syllable of the words matched in Stalling’s arrangement foreshadow memorable instances such as the elaborate opening to Jones’ Rabbit Seasoning.

Burma-Shave shaving cream is to thank. Spanning from the ‘20s through the ‘60s, the company memorably dotted the roadsides of nearly every state with their rhyming barrage of signs and slogans. Typically, there would be a total of 6 horizontal signs all arranged in a line: 5 of them would make up a rhyme, and the last one would serve as a marker of Burma-Shave’s presence through name. You can read more in-depth about their history here.

Thus, we get our first glimpse of the dog—er, dog house. Naming the dog “Spike” is, of course, one of the biggest cartoon cliché in the book (but seems unfair to call it one when the novelty was much fresher in 1941 than it is 82 years later.) It also happens to be a cliché for a reason: it instantly cements an image of the dog in the mind of the audience, if the signs weren’t enough of an indication. Only showing his dog house rather than Spike himself is its own brand of intimidation—we know he’s nearby, but have no idea what he looks or acts like. The suspense is pivotal to justify the cat’s trepidation.

Tugging on the chains that lead into the doghouse milks that apprehension just a bit further. They don’t budge or easily come apart, indicating that there is a force dwelling within the dog house that maintains such a physical and metaphorical tension.

Courtesy of a few genial knocks, the audience gets their first glimpse of Spike. He looks exactly as his name would suggest—probed collar, giant jowls, menacing underbite, and a prominent too heavy stance that is immediately poked fun at through his awkward, bow legged entrance. Menacing as he is established to be, his curt, absurd movements as he marches forth seeks to dispel the heaviness of the atmosphere and introduce a comedic element to the dynamic that still maintains the conflict. That is, he is genuinely scary, justifying the cat’s apprehension, but almost absurdly so. He’s a caricature of himself. He proudly adopts the stereotypes that the cat and mouse are seeking to disestablish.

Ever cleverly, Freleng utilizes the close registry of the camera as a springboard for more personality and humor regarding the cat. The camera trucks out to reveal an empty yard and a befuddled Spike; the nervous chuckles that soon follow are communicated from off-screen. Sharing our disorientation, Spike sheds a few clueless head shakes as he struggles to discern the location of his visitor slash victim.

Said head shakes are awkwardly stylized through some unnecessary drybrushing—the dry brush in itself is fine, as the movements are quick and abrasive enough to warrant it, but the brush strokes are animated to fly into the air as though they are physical objects. Thus, the intent of the decorative flourishes is lost and adds visual noise to the screen rather than serving the action. A small critique, but intriguing nonetheless.

Even the camera doesn’t seem to know where to locate the cat. There’s a slight pause as it pans forward to reveal only nothingness—scooching towards an open barn door doesn’t help much either. The maneuver follows the same philosophies mentioned in the review of The Crackpot Quail, where the camera itself plays a bit role, thereby rendering the cartoon more immersive and giving it a stronger voice.

An answer lies not horizontally, but upwards. Courtesy of some warped perspective, the camera travels up to reveal the cat perched on the very top of the door. By warping the painting itself—having the door follow a curved perspective that varies from the initial flat staging—the height difference seems much more extreme. Much more extreme comparatively than if the camera had merely slid upwards with the same static perspective, keeping the cat eye level. Height takes the priority.

Blanc continues to make his vocal mileage count with the natural, warm, awkward charm of the cat. Anxious chuckles instill a constant vibrato in the cat’s voice, which greatly support his default milquetoast tone.

In spite of how unconvincing his voice sounds regarding his confidence, the cat finds enough security to finally jump onto the ground. Gil Turner’s handiwork dominates the next minute and a half of dialogue (yes, more monologues!); his draftsmanship isn’t nearly as tight as Bickenbach’s, and has a tendency to always have his characters idly moving on screen. It can become a bit of a distraction, but he is good at depicting a sense of flow and motion. Timing on the dog as he rapidly chews on his bone in drone-like vacancy is mechanical in all positive connotations of the word, and juxtaposes nicely against the cat’s idle swaying, shuffling, and gesticulating.

If the mouse’s spiel went in one ear and out the other with the cat, then the cat’s spiel doesn’t even fall on the dog’s ears at all. One gets the sense that his ignorance isn’t out of a purposeful stubbornness. Rather, he seems too stupid to comprehend it. The only thing that matters to him is his bone. He is the ultimate servant to his instincts. While the cat is somewhat cognizant enough to learn to defy his own instincts, uncomfortable as he may be doing so, the dog doesn’t seem like he has the capacity to entertain the idea. Indeed, the hierarchy is enforced from most to least rebellious—mouse challenging social norms the most, and the dog the least.

More reused animation of the cat hopping down from the door follows after he is inadvertently sent back up. “Inadvertently”, because it’s entirely instinctual; as soon as the dog moves his paw, the cat takes off like a rocket and returns to his safe haven. So much for looking firm in his argument.

Adding insult to injury, the move of the dog’s paw serves merely to scratch his head. He seems mildly confused, indicating that there is some awareness of the cat… but the pleasures of his slobbery bone prove to be more enticing.

Amidst further rambling, the cat slips the line of “You’re a smart man!” into the mix. Very subtle, Maltese-ian humor that is amusing through its implications; we don’t know much about this dog, but we do know that he is definitively not a smart man.

It takes the cat putting his foot down (as broadcasted by him personally) to actually nab the dog’s attention, and even then, that’s only because of a fatal mistake: the cat accidentally sends the dog’s water bowl toppling onto his head. Sharp eyes will notice that the bowl is cheated closer to the dog house than in previous shots—such makes it easier for staging and clarity, and ensures that the cat’s gesture is purely accidental. Having him scoot the bowl over would be too contrived and purposeful of an action. Instead, Freleng counts on the viewers to be too distracted by the cat in the prior shots to pay much attention to a seemingly innocuous background detail.

Rather than having the dog rip the cat to shreds right then and there, Freleng and Maltese opt to milk the tension some more. A slow burning awareness from the dog has been established and continues to broil as the cat awkwardly attempts to dry him off; it seems that his attempt to make do—dabbing the dog off with a towel, flipping his ear back to its original position—put him even more on the chopping block than if he had just made a break for it.

Similar notes of the mouse inspecting the speck apply to the cat flipping the dog’s ear over. Coloring errors on the ear unfortunately encourage the action to get lost—the outer and inner ear colors switch and flicker, as though the inker was confused about what position the ear was truly in—but including such a detail successfully exacerbates the cat’s sucking up. Likewise, it’s a very human detail and keen observation of how dogs move (or, more accurately, how their ears are moved.) Its arbitrariness makes the cat seem even more pushy in his niceties; just drying the dog off is more than enough. Instead, he’s committed to establish his loyalty.

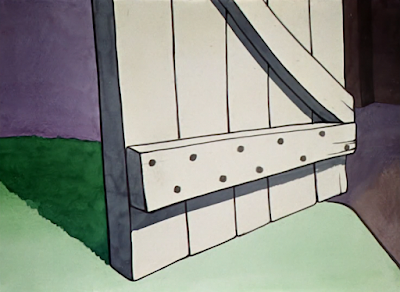

Amidst further ranting and raving, Freleng cuts to a close-up shot of the shed door closing. It seems like a wholly innocuous detail, something to divert the audience’s attention away from the talkiness and repetition of shots… but proves to be a somewhat important caveat: if the cat gets scared, he can’t run to his perch for safety. He’s in the thick of it now. Leaves are animated as a brief overlay to visually communicate a breeze, thereby justifying the door’s closure.

That comes into play soon after; as the cat mocks the dog for being chained up, he quickly discovers that the opposite is true. Before, he had only been tugging on a small portion of the chain and not the whole thing. The reveal is solid, with the end of the chain keeping it down having been cheated out of the frame until the very last second to maintain the surprise. Its sudden appearance to justify the cat’s reaction is smoothly incorporated into the animation.

“He ain’t chained… he ain’t chained!”

Mel Blanc gives us several variations of the same line. About five and a half minutes into the cartoon, the novelty of the extended dialogue has run its course—with so little having happened, the audience hungers for action. Thankfully, we are closer to that goal by the second, but the talkativeness prevails. Regardless, Blanc does a fine job making the dialogue nice to listen to. There lies plenty of character within those nervous chuckles.

A full on perspective shot of the dog approaching the camera serves primarily to introduce further empathy with the cat. By putting the audience in the cat’s eye level, they are directly thrust into his shoes, and feel as though they are the target of those bared fangs and bristling hairs. The desire to flee feels much more understanding. There’s always the benefit of the perspective encouraging dynamic staging and variation in shot flow as well; always a bonus.

There’s a clever fake-out of the shed door (or lack thereof) through recycled ideas; as he did before, the cat engages in the same spastic whirlwind before launching into the air and on his perch. Said perch is, of course, non existent, as he soon realizes for himself when succumbing to the laws of gravity. It’s a little gesture—one that pads more time rather than actively contribute to the drama—but makes the cat seem more vulnerable now that his safety hatch has been taken away from him.

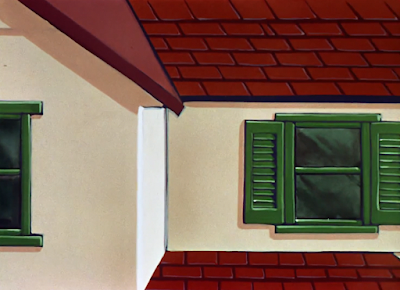

Paul Julian’s induction in the Freleng unit within the next year would be greatly appreciated, as this shot of the cat and dog running into the house establishes. In more direct terms: the background is ugly. A periwinkle outline dominates the house, shed, and some decorative trash cans—it looks better with the light cream colors of the stairs and rails, but less so with the red of the shed or window shutters. Likewise, the paint strokes themselves feel thick, unregulated, directionless. Backgrounds all through the short have a tendency to be varying degrees of muddiness, but it’s certainly at its most pungent here.

Thankfully, things start to solidify comparatively as the camera pans to reveal the remaining façade of the house. Considering the house’s exterior is the only thing the audience sees for the next 25 seconds, that proves to be a benefit. Indeed, all of the chase between cat and mouse unfolds completely off-screen—only the pan of the camera, the sound of the chain dragging and an occasional meow or two hints at any action.

It’s an economical approach for sure, and does deserve to be noted given that this short in itself seems to be very aware of its economy through reused animation, long stretches of dialogue, and using background elements to hide behind. So, it very well could be interpreted as one giant cheat, and to argue otherwise would definitely be somewhat disingenuous.

Yet, at the same time, it is a very clever approximation of a chase. There’s no background accompaniment of any kind: just the din of the dog’s chain dragging up the stairs and the plastic thundering of footsteps. Thus, the viewer’s attention is solely attracted to the action, which is made both amusing and imposing through the sound effects. The camera moving from one end of the house to the other, diagonally and horizontally, is another sharp way to paint a phantom picture in the audience’s mind.

Not a single bark is emitted throughout the entire chase. Nor a growl, nor a snarl. It proves to be somewhat disconcerting, but also, in an odd way, furthers the dog’s “invincibility”; he doesn’t feel the need to threaten verbally, and doesn’t feel threatened enough by the cat to bark, either. Regardless, bark or no bark, the audience can summarize that the cat isn’t going to come out of the situation on top.

A fade in does not return back to a decrepit cat, but his mouse companion instead. He lounges in the cat’s bed, filing his invisible nails; the lazy accompaniment of “Trade Winds” paints his new pleasures as a getaway, a paradise of privilege. Him camping in the cat’s bed is a ballsy move in itself—to do dismissively file his nails like that indicates further conceit through such leisure. Here he is lounging and enjoying himself, while his plan nearly got the cat killed.

Indeed, the camera makes a jump cut to reveal the cat in his decrepit condition: bandages, sling, and a facial expression that drips with contempt. Sudden as the cut may be, it is successful in conveying confrontation and intensity.

Cal Dalton animates the remainder of the confrontation between cat and mouse. His style is immediately recognizable through the way in which he draws mouths—wide, angular, often with accompanying wrinkles. Emphasis in acting primarily rests in the movement of the head. Likewise, he’s been known to draw characters with a little more paunch; indeed, both the cat and mouse seem a bit more full than in other shots. His drawings of the cat especially are very charming.

Blanc does a fine job sustaining the cat’s genial vocals, even/especially to contain his thinly disguised anger. He communicates with the mouse in passive aggressive answers: “No, he just couldn’t see it your way,” is his disdainful explanation of the aforementioned conflict.

It’s only then that the mouse shows some genuine awareness for the cat. Aloofness is soon abandoned for anxiety as he realizes that the cat is going to continue chasing him—that is justified by the cat himself through a slow, condescending “Mmmmm-hmmmm!”

Aggrieved by his injuries as he may be, the excess bandaging still doesn’t get in the way of the cat’s desire for revenge. Said bandages are thereby shed as the cat launches out of them and the chase resumes.

Thus, the cartoon ends exactly as it started: a frenzied cat and mouse chase over and under the furniture. Again, reusing the same animation proves to be a cheat, but does admittedly aid in strengthening the solidity of the bookend.

It moreover justifies the mouse’s gripes of “The same thing again!”, again animated by Dick Bickenbach. We see a reprisal of his spiel with the same chest puffing, fist balling aggression. Same mission to talk some sense into the cat, same query of the age old question: man or mouse?

“…”

Before segueing into the conclusion, the ending of the cartoon deserves to be noted. Not the iris out—what comes after. Interestingly, this short touts a unique arrangement of “Merrily We Roll Along” that’s independent of this cartoon alone. Chords seem to be more layered and rich, notes briefly adopt a staccato swing (which a woodblock is heard accenting), and the arrangement as a whole sounds more lush and triumphant. You can hear it for yourself below:

It’s not unusual for some of these cartoons to flaunt one-time spins on arrangement. The next short, Joe Glow the Firefly, perhaps boasts the most memorable twist on “The Merry Go Round Broke Down”; cartoons such as Puss ‘n Booty and Acrobatty Bunny have their own subtle changes as well. Reasoning for these changes is relatively unclear—it very well could just be Carl Stalling and Milt Franklyn having some fun and itching for variation. Intentions aside, it makes for a rather amusing scavenger hunt.

Back to the cartoon at hand; The Cat’s Tale is a very economical cartoon, in both a positive and negative sense of the word. Its cons are admittedly more visible: it’s extremely reliant on dialogue to a bit of a fault, which leads to static staging choices. Lots of cuts between characters talking or elongated shots of them both in the same plane. Animation is recycled wherever possible, and opportunities to withhold animation as a whole are certainly taken advantage of. These shortcuts do come to be rather noticeable—especially as they seem to keep piling on.

Yet, there’s a certain admiration inherent to such measures as well. Economical as it may be, Freleng does what he can to make it count. With most instances, there lies a justification for their cheats: the beginning reused at the end allows for a stronger book-end and strengthens the irony of the mouse’s spiel. Depicting a chase entirely off-screen and with minimal sound effects proves to be rather memorable through its stylization. Blanc does what he can to make the incessant dialogue count, and animators such as Dick Bickenbach do what they can to accompany it accordingly in their drawings. There seems to be a larger sense of purpose with these cheats and reuse than, say, Bob Clampett’s definition of a cheat. At the very least, Freleng makes a stronger effort to disguise or justify these decisions.

As a result, this short isn’t intensely interesting; there is a lot of standing around and doing nothing but talking. A lot of character can be found in said talking—there are amusing motivations and lines—but it never seems to end, and that becomes a bit taxing.

It is nevertheless an amusing premise and a smart one at that; Maltese’s hand in the writing is exceedingly noticeable. However, both Freleng and Maltese especially would create stronger, more subversive cartoons to much greater effect, chase or not. After all, Mike Maltese has a hand in creating one of the greatest parodies of chase cartoons of all: the Road Runner series.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment