Release Date: March 15th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Fred Uh-ver-y

Story: Dave Muh-nah-han

Animation: Charles Mac-Kimson

Musical Direction: Cahl Dubya Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Cecil, Chester, Turtles)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

If Elmer’s Pet Rabbit serves as a hint to Bugs’ permanence as a character through being the first successor to A Wild Hare, then Tortoise Beats Hare drives the nail in the coffin. To have a follow-up by another director is one thing—for the “founding father” to direct a successor is another.

And yet, in spite of Hare’s massive popularity, this follow-up almost didn’t come to be.

My good friend Devon Baxter recently posted an incredibly thorough analysis on this very cartoon. If you have even a fraction of an interest in animation history (which, given that you are reading this right now, I hope is the case), then do yourself a favor and spend the next ten minutes glossing over all of the information he’s carefully curated. In addition to uncovering an animator’s draft, he also provides a wealth of knowledge surrounding this cartoon’s production and audience reception. I will be relying on both of these aspects throughout my own dissection of the cartoon, so I implore you to go straight to the source and get all of the facts for yourself.

Thanks to Devon’s research, we know that—according to Bob McKimson—Avery wasn’t keen on the idea of doing another Bugs cartoon. It took the persuasion of production manager Ray Katz and McKimson’s own fondness for the character to win him over. Says McKimson in his own words, “He knew that I liked to animate on Bugs and liked to work with him, and so that was how come he made even the second one.”

Evidently, the bartering process between Katz and Avery wasn’t a long one. Animator Rev Chaney’s work ledger reveals that the cartoon was already in production as early as August 20th—not even a full month after the July 27th release of Hare. Likewise, under the preliminary title of Tortoise + Hare, the cartoon was officially inserted into Avery’s production schedule as of September 22nd—just a few days after Bob McKimson drew up some model sheets of Bugs that differed than Bob Givens’ model seen in Hare.

It was a successful gamble from Avery. While Tortoise may not have received the same Academy Award nomination bestowed to A Wild Hare, it did receive a comic book adaptation, a conjoining record and storybook adaptation, a brief spinoff series in the Dell comics with one of the turtles in this short, and its own trilogy of shorts: Bob Clampett’s Tortoise Wins by a Hare (which, in endearing Clampett fashion, reuses footage from this cartoon) in 1943 and Friz Freleng’s 1947 follow-up, Rabbit Transit. Each installment in this series is better than the last: Wins by a Hare happens to be my own all-time favorite Bugs cartoon.

Already, Avery was making refinements to the personality he had established in Hare. Bugs maintains his nonchalant carrot chewing and his thick, Brooklyn accent, and his looks are relatively the same—some scenes seem to have used McKimson’s model as a reference over Givens’ and vice versa, but the difference mainly applies to the distribution of proportions.

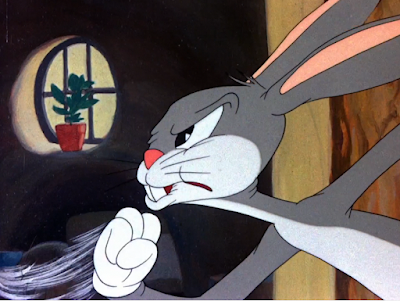

There does stem one major difference, however: Bugs’ skin is revealed to be quite thin.

Indeed, he serves as the inverse to his unflappably cool demeanor in Hare. Upon learning about the cartoon’s title, he grows irate and tears into a frenzy, searching for this elusive turtle who’s positioned to beat him. Beat him at what, he doesn’t know. Nor does he care. He just knows he has to settle this once and for all and asserting that all of hare-dom will come out on top—that, of course, is settled through a race.

Comments about McKimson’s fondness for Bugs manifest as early in the cartoon’s opening. It is he who animates one of the most powerful fourth-wall breaks touted by these shorts thus far—Bugs strolling along and reading the opening titles.

“Reading” is a term used very liberally. He mispronounces every single name presented in front of him, save for Carl Stalling’s; compensation is delivered through a stutter on “Musical direction”. It’s a fantastic bit that is wholly carried through the nonchalance and organicism of Blanc’s vocals, which is given an appropriate vessel through McKimson’s equally natural animation. Stalling’s perky accompaniment of “Mutiny in the Nursery” not only proves helpful in hunting at the fairytale thesis of the cartoon, but likewise maintains its own independence that doesn’t call too much attention to Bugs’ recital of the credits. It’s just something that happens, a little glimpse into Bugs’ life. Not a meticulously planned spectacle.

Learning that Avery reused this gag later on in his career doesn’t come as too much of a surprise; the best of his gags or situations at Warners were often polished and refined to further excellence over at MGM. In this case, The Screwy Truant and Swing Shift Cinderella borrow the format with two characters instead of one. Yet, the influence of this opening was more far-reaching; Famous Studios was the first to adopt it with their 1943 cartoon, The Hungry Goat. That the first imitator of this gag wasn’t even Avery himself speaks to its effectiveness in making an impact on the audience.

Even with that in mind, no amount of homages or reprisals of the gag could ever beat the sheer excellence that is presented here. Primarily because it is perfectly tailored to Bugs’ character and role in the story; even as early on as here, Bugs has more dimension in his personality than Screwy Squirrel. His reaction towards the title stems from sincerity, whereas Screwy is solely there to entertain.

“Tortoise…. Beats… Hare.” The audience almost feels as though they’re sharing the carrot with him, his deliveries are so thick and chunky. Perfect in conveying his indifference.

So, the violent spitting of his carrot chunks that follows moments later serves as a visual accompaniment to his immediate dismantling of said indifference. Blanc perfectly captures the crescendo of realization as Bugs repeats the title a few times in a dumbfounded stupor.

“Tortoise…” McKimson, ever maintaining a keen eye for detail, depicts the pause through a brief swallow. “Tortoise Beats Hare?”

With the remnants of carrots now free of his mouth, Bugs is able to recite the title at the top of his lungs as freely as he wishes. We therefore are able to witness the thin-skinned irritation hinted at in the introduction—he rants, he raves, he yells, his gestures are accusatory and proud. It’s almost as though the audience is getting a glimpse of what the true Bugs looks like “after hours”; he can play it cool in front of a gun, but when caught off guard for a scenario he hasn’t rehearsed, he’s commanding and impulsive, braggadocious. A very stark contrast to his smug sense of calm so prevalent through A Wild Hare.

Still, this is the same rabbit. That’s justified through a much more cool-headed and controlled aside to the audience curtailing his raving. His Groucho Marx-isms take the reigns, if only for a split second.

“Why, ‘dese screwy guys don’t know what ‘dey’re talkin’ about! Why, da big buncha joiks!”

“…An’ I oughta know. I woik for ‘em.” McKimson perfectly handles the comparative elegance of his false modesty, which is accented through Stalling’s demure flute sting.

All of the opening presented thus far is great. Again, its greatest strength that its imitations lack—even those by Avery—is that it is personally tailored to Bugs’ needs and personality. It feels remarkably natural, doesn’t seem as though the pace of the cartoon has come to a crashing halt to entertain this bout of meta humor. It’s just a day in the life for Bugs. Avery’s direction is great. McKimson’s animation is great. Blanc’s deliveries are great. Stalling’s music is great. It’s all great. Each part of the whole support each other and collaborate to make a very cohesive product.

Yet, the best part stems from Bugs tearing away the title card himself and marching directly into the cartoon. Animation of the card actually being torn to shreds is very convincing—there are no telltale errors of cels clipping over each other unnecessarily or any egregious blank spots. Both the background element of the title and the cels of the paper—not to mention Bugs himself on another layer—have to work in strict conjunction for this to pay off. The bottom of the screen shouldn’t be blank if Bugs is still tearing off a shred from the top. No, it’s a very well coordinated effort that is able to solidify and be cemented through the aid of Treg Brown’s tearing sound effects and Blanc’s circuitous raving overtop.

.gif)

He thusly resorts to home invasion as soon as the last shred of title card is thrown out of view. To have him immediately rush to the object of his wounded pride’s home would be too perfect, too calculated. Instead, darting into two other homes before stumbling upon the conveniently labeled “CECIL TURTLE” mailbox instills a reckless vulnerability that highlights his impulsive rage.

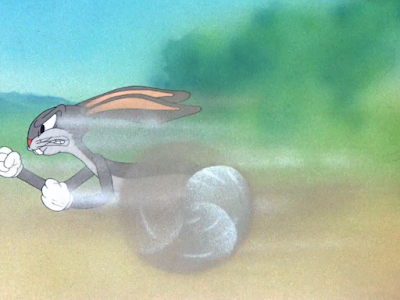

More remnants of his self in Hare briefly manifest through a dry brush whirlwind as he stood at the door; it’s exceedingly reminiscent of his similarly whirling exit out of his rabbit hole in the former cartoon. While that was a segue into leisurely, collected heckling, the whirl a symbol of his playfulness, it serves as a representation for how wound up he is here. Caught in a tailspin of pride.

Virgil Ross steps in to animate Bugs pounding at the door. His Bugs in this particular section is depicted rather abrasively, with a scrunched nose and visible, gnarly teeth aiding in his malice. Gestures are broad, loose, and elastic, periodically supported by a coating of dryer brush to give an added manic flair. Animation of Bugs’ arm swinging into the foreground is particularly nice through its perspective. His work may not be as controlled as McKimson’s (who’s was?), but control is not what Avery is looking for in this moment.

“C’m’outta dere! Or I’ll huff… an’ I’ll puff… an’ I’ll bloooow your house in!”

Somehow, Blanc manages to lower the register of his voice seamlessly in real time. He dips out of Bugs’ nasal register and into a deeper, guttural boom without a hiccup or a crack whatsoever. His versatility is nothing new, being The Man of 1,000 Voices, but to hear that transformation unfold note by note, pitch by pitch, register by register truly puts his vocal prowess into perspective.

He demonstrates the same amount of ease by slipping into Bugs’ familiar nasal strains for his next line: “Oh, uh… sah-ree, pahdon me. Wrong story.” Given Avery’s growing accumulation of fairytale burlesques, the line is made even more amusing.

Compared to McKimson’s introduction, Ross’ animation is loose and mean. If that’s the case, then the following cut to Rod Scribner is even more loose and even more mean—just the way he liked it. Wrinkles, gums, and teeth tender Bugs particularly nasty, perfectly complimenting his rage. Both Scribner and Bugs’ emotions seem to boil on the screen.

There does stem an awkward camera move for the sake of a staging gag. After cutting to Scribner’s animation, the camera makes a hasty, shaky trek towards the upper left part of the screen. Such is to hide the fact that Bugs’ turtle adversary, this ever elusively named Cecil, is a complete pipsqueak; he’s not the tall tortoise Bugs (and possibly the audience) made him out to be.

Thus, his reveal as the camera trucks out gets a much bigger laugh than if Cecil opening the door and standing in the doorway had been depicted on-screen. It’s a necessary move, but one that feels somewhat unsteady through the path the camera takes in achieving this.

Scribner does a fine job maintaining his “ugliness” to Bugs. Cecil doesn’t share the same bared teeth or excessive wrinkles—nor should he, given that’s not in his current motivation. He looks much more cute and polite in comparison, which is furthered through his demure, neighborly “Uhh… hello!” Bugs, with all of his bared teeth, wrinkles, shaking fists and threats is made to be quite the horse’s ass in comparison.

Of course, Bugs’ pause is only temporary. Avery dips his toes into an almost uncomfortable level of abrasiveness as Bugs physically picks up Cecil to jostle him, continuing to threaten him (and the empty turtle shell in his hands as Cecil slips through.) Some of that discomfort stems much more from a modern perspective—we’re so used to seeing Bugs remain high and mighty and unflappable in even the gravest situations, that to see him get so violent over a complete non-threat at all is disarming.

Still, this doesn’t come as a complaint—especially since Avery had no idea what his character would evolve into. Instead, it presents a fascinating novelty, and a glimpse into a time of flexibility where Bugs could get away with acting like this. One wonders how soon this behavior would have been flagged if the cartoon were made 10, perhaps even 5 years later. His development was so rapid and so right—all of the pieces falling into place where they needed to—that this behavior is a sort of sacred gem in itself. Even in Tortoise Wins by a Hare, where Bugs’ manic behavior garners similar discussion, he was never this vitriolic to Cecil’s face.

The whole point of this sequence is to indicate of much of a sorehead Bugs is being. If his aggressive actions weren’t indicative enough, Cecil’s patience, politeness, and coy demeanor (such as the cutesy manner in which he hides his undergarments) provide a juxtaposition of “purity” that makes Bugs look even worse. Likewise, it should be noted that for all of his motor-mouthing, speechlessness settles in each time Cecil opens his mouth.

Cecil’s stature offers ample room for visual gags, primarily with his shell. Thus, Bugs’ threats are made more amusing through the cushion of amusing visuals; it proves difficult to be wholly unnerved when he’s stuffing his head into Cecil’s shell. Blanc’s vocals are distorted through a tinny, echoing sheen to bestow a coinciding permanence with the gag. It cements that Bugs is indeed violating every inch of personal space that Cecil once had.

“You know darn well dat I kin beat’cha any day a’ da week!” There comes a pause, as though Bugs himself isn’t entirely sure of his words. Added reaffirmation is pushed through an additional “Ya know dat, don’t’cha?”

The response of “Uh… no,” could not be more perfectly timed nor delivered. It’s rooted in honesty, it inflates Bugs’ status as a jerk, and it has just enough of an exasperated edge on behalf of Avery’s directorial commentary to get a laugh.

Chuck McKimson receives the metaphorical baton after Scribner to animate one of the most pivotal story points: both agreeing on a race. Some of McKimson’s trademarks visible under the direction of his brother can be seen here—particularly the manner in which Bugs lunges his body forward and backwards. Movements are weighted and full of intensity, which are softened by the follow-through on his ears. A very visually rich outcome that often wasn’t the case for his animation in Bob’s cartoons, though much of that is owed to the scenes Bob would assign him and the growing limitations of his art direction over Chuck’s incompetence. This very scene was not animated by someone who is incompetent.

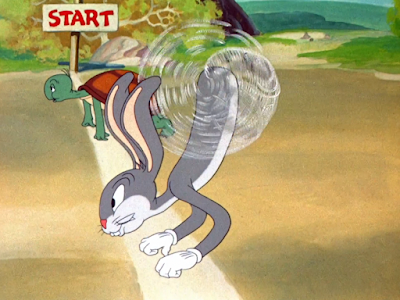

Thus, riding on a $10 wager ($214.89 today, to justify the loftiness of the stakes), animation switches back to Virgil Ross as we dissolve to our heroes at the starting line. Even before he’s begun, Bugs is a sore not-yet-loser, jeering at his opponent and calling him names. He is again constructed to look like a jerk, particularly through Cecil’s mindless honesty and peaceful obliviousness. While Bugs spends his time laughing at him, Cecil does what he can to warm up. Nicknaming him “Seabiscuit” and asking if he’s all set rouses the truthful, borderline jejune reply of “Yeah, I guess so.”

Animator Rev Chaney is the all important indicator of the race’s start. All three tortoise vs. hare cartoons have Bugs attempting to get a head start in some way, and it’s thanks to this cartoon that such a pattern is established. While he doesn’t physically cross the starting line, he kicks up his legs and takes off in a whirlwind of speed. He doesn’t even have the courtesy to signal “GO!”, screwing Cecil out of a fair race. Then again, none of Bugs’ behaviors in this cartoon exude any sort of “fairness”.

Cecil mimics the same whirlwind, sound effects manifesting through juvenile squeaks over Bugs’ intense airplane engine sounds. Regardless, the audience is almost led to believe that Cecil may receive an appropriate running start after all.

Wrong.

However, he isn’t completely dissolved of any allegations of duplicitous behavior. After a handful of lugubrious gallops (expertly timed to give him a molasses weightlessness to caricature his lack of speed), a grin beams onto his face. It is soon revealed that the stray path indicated in Johnny Johnsen’s background has a purpose, as Cecil takes a detour. To Johnsen’s credit, the path is clear enough for the audience to go “Oh, of course,” but manages to blend into its surroundings with enough innocuousness to not give away too much information. Shrubbery and rocks frame the path to both guide attention to it when necessary and allow it to blend in.

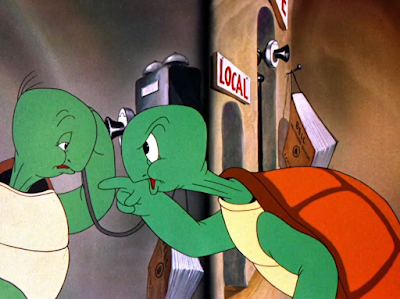

More tricks reside up Cecil’s sleeve than initially thought: said path leads him to a turtle branded phone booth, indicating that he’s gotten plenty of use out of it before. This reveal is pure Avery, and feels like something right out of his MGM cartoons—the cartoon Screwy Squirrel also features a phone both proudly residing in the middle of a meadow. Here, Avery attempts to make the booth live within its environments, building it into a tree so that it doesn’t seem too much of an incongruity. By the time of Screwy Squirrel, that wasn’t a concern.

Sid Sutherland depicts Cecil’s arrival and entry into the phone booth, which heralds one of Avery’s favorite pet gags: a long distance phone that is indicated through its long neck. That the indent in the tree is carved to be as long as the phone itself proves to be a nice topper.

Clever as he may be, Cecil is still—of course—a turtle. It takes him a moment or two to mull over which phone he wants to use; Sutherland’s animation makes it look as though he’s really laboring over the decision. He still takes everything slow, as he is bound to his role as the tortoise in the fable, burlesque or not.

We switch to more animation from Chuck McKimson as Cecil asks for a “Chester Turtle”. So, with such similar names, it makes sense that Chet not only looks exactly like Cecil, but sounds exactly like him too.

“Chet, y’know that slicker rabbit I made the $10 bet with?”

Chester’s obedient answer of “Yeah?” is a gag in itself—there is absolutely no way he could have known about any sort of bet if he wasn’t there. His nonchalant answer and how the two continue on the conversation like normal is all a part of Avery’s credo. Characters can be as aware or as unaware of the cartoon as they wish, even if they weren’t there to witness said events. It’s a very subtle but amusing acknowledgement of Avery’s continued embrace of metaphysical humor.

Which, of course, is hinted at through the manner in which Cecil leans over the screen divide to give his instructions. This, of course, isn’t the first time Avery has used such a device—

Thugs with Dirty Mugs and

The Bear’s Tale come to mind. Still, it exists to embrace Avery’s love of defying cartoon convention and for the sake of instilling an amusing visual.

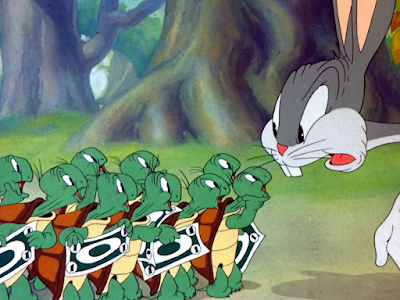

Through the phone call, Cecil lays out his plan: call up “the boys” for them to be ready whenever Bugs passes them in the race. That way, Bugs will always believe that Cecil is ahead of him no matter what. It’s a clever solution to the “tortoise versus hare” equation—the turtle doesn’t win because he has better morals than his opponent and just sticks to his own pace. He wins through a duplicity that is more subtle than Bugs’ own, yet more successful. Bugs may be able to beat one Cecil—ten Cecils is a different fable.

Thus, we are soon reminded of Avery’s eye for cinematography through means of a montage. As mentioned in previous reviews, Avery’s eye for directorial splendor doesn’t get as much buzz as his knack for gags or speed, but he certainly knew how to elevate a scene’s visuals or emotions when necessary. Various dissolves between diagonal angles, close-ups, synchronized actions and so on instill a certain bombastic effect that feels like a genuine call to arms.

An urgency that isn’t all that urgent—maybe not to us humans, but certifiably for tortoises. The obedience in which they answer and abandon their everyday activities (which both humanize and distinguish them apart from everyone else, asserting just how widespread the calls are reaching… including a spacious lake for added playfulness) makes it seem as though they’ve been waiting a long time for this moment. Or, perhaps it’s routine at this point—who’s to say there haven’t been other rabbits with an ego problem who have initiated this same setup time and time before?

Nevertheless, this short only focuses on one rabbit with an ego problem. A cut back to one of the Not Cecils waiting behind a tree is a bit sudden and out of left field, as the difference in tone is a bit strong; a cross dissolve would have been more efficient in softening the blow and easing the shift in ideas.

It nevertheless doesn’t impede the clarity of what’s on screen. “Cecil” runs ahead as Bugs creeps closer into view, hopping along like a rabbit. Said hopping (in conjunction with the flighty musical accompaniment) demonstrates a drastic shift in tone and character compared to what Bugs was exuding in the beginning—there’s an innate playfulness that juxtaposes against the earlier intensity. He has the time and leisure to be playful since he’s so confident in his abilities.

All of the above are justified through a close-up shot of Bugs’ various hopping methods. Soon enough, he’s skating on the dirt, kicking off with his feet and leaving a steady trail of dust behind him. The action is nicely weighted, with the kicks having a genuine kinetic shove to them. Smoothness of his gliding creates an appealing visual balance against it.

Bugs’ delayed take—beautifully animated by Virgil Ross—is a thing of beauty through how simple it is. It’s just a held frame from the skating cycle; no additional antics or any follow-through that would soften or hint at his surprise. It’s incredibly sudden, which captures his jolt of realization much more believably than a wild series of head shakes. Likewise, it doesn’t happen immediately. A few more rotations of his skating cycle add a hearty cushion between his passing the turtle and the eventual realization to create a believable delayed reaction. It furthermore allows the audience to be forcibly shaken out of the visual routine when the take does come.

A wide eyed stare at the camera allows Avery and Ross to inject some more motion in the character—still petrified, but the slight raise of his leg gives him life and some differentiating visuals.

“Differentiating visuals” in the sense that he does another completely static take once he zips back to the turtle. To have all three takes be the same would lose their impact comparatively; instead, his reactions carry a very methodical rhythm.

His final surprised take as he jumps into the air follows the same philosophy of the second one, in that there is enough idle movement to be juxtaposed against the static reaction before it. Very controlled planning that results in a very seamless visual product. His frozen reactions are more visceral and emotional at its core than what a distorted wild take with more visual grandeur would allow. Boldness in simplicity.

Stalling’s musical accompaniment for Bugs’ “interrogation” (a series of strangled questions that quickly fade into nothingness) successfully captures the aforementioned sense of strangulation. It isn’t so much a musical score as it is a series of harsh music stings—quick, short, alarmed, representative of Bugs’ own abbreviated statements. It’s a score that’s wholly indicative of emotion, representing his fragmented thinking rather than serving to please the audience’s ears through a memorable tune.

Of course, the beauty of his interrogation is that it’s completely meaningless. As we just saw, he passed his current opponent—he’s losing valuable running time by stopping to gawk and froth over the turtle’s presence. Another commentary on his ego and how his pride, at least in this cartoon, can lead to destructive tendencies or outcomes. It doesn’t matter that he passed the turtle, or even that he’s really there—what does matter is that it implies he was ahead of him and not behind, and that makes Bugs look like a loser (if only for a short while), and he might as well be dead for it.

Aforementioned spinning head takes do eventually manifest on the rabbit after “Cecil” gives his alibi: “Oh, uh… jus’… runnin’!” is his secret to getting ahead. Such a simple non-answer is too infuriating for Bugs to process.

A great piece of foreshadowing/justification to Cecil’s plan are the boxers on the turtle as he slips out of his shell. Sharp eyes—or, at least, eyes that aren’t Bugs’—will note that the pattern on the boxers are red pinstripes. Cecil’s own undergarments had red dots on them. It’s a very subtle change that doesn’t seek to call attention to itself, but is noticeable enough for the audience to know that this is a different turtle. Bugs, of course, is too blinded by prideful rage to ever notice.

Realizing he’s losing valuable time, Bugs takes off like a rocket; the whistling sound effects, the steady stream of dry brushing, and general speed as a whole indicate a familiar ferocity and dedication to racing that wasn’t present in his leisurely hops or glides.

But, of course, that’s only temporary. Bugs’ attention span proves to be fragmented as his conceit continues to nag at him—he stops now to have a brief moment of confidentiality with the audience, wondering how the turtle could have been “back ‘dere.”

Bob McKimson’s character animation of Bugs is gorgeous. His draftsmanship is one thing—solid construction and perspective, general appeal in the character—but his acting and how it fits Bugs’ personality, needs, and supports what he’s saying is another. With his points, head tilts, snaps, sweeps, and other gestures, the result on screen feels much more akin to a carefully staged performance rather than him ranting about the turtle’s sudden appearance. Stalling’s musical accompaniment is attuned perfectly to the vocal cadence in Blanc’s deliveries, which, in turn, is matched through McKimson’s careful animation. It’s a stunning piece of character animation that seems to flourish in all the right places.

Ditto for the sudden appearance of “Cecil”. Nonchalant yet quick, choreographed to justify Bugs’ ranting. Likewise, Bugs’ subconscious pointing and acknowledgement of the turtle’s presence (without actually realizing it’s him) gives the turtle’s introduction a further springboard for clarity and snappiness.

Same with his “Hullo,” between Bugs’ sentences. Every little detail and decision feels meticulously planned, but not in a way that is mechanical or stilted. Rather, it’s incredibly humorous through such utter convenience. It’s as though the two characters rehearsed this as a sort of vaudeville act, obsessing over the timing of the deliveries and entrances for the strongest comedic impact. Instead, this is all meant to occur “naturally”—no rehearsal, no collaboration between the two, no nothing.

“I tell ya, it just

don’t make sense!”

It is here where the cartoon delves into a quasi-chase cartoon. The idea of a little, seemingly omnipresent pest popping up at will and tormenting its opponent would result in some of Tex Avery’s most notable cartoons, and has been a setup he’s established years earlier.

The Blow Out, released in early 1936, was his first attempt at this formula, with Porky as the omnipresent pest. His motives were more earnest and juvenile, of course—wanting to return a time bomb (unbeknownst to him) to its owner so that he could get paid for his good deed and buy himself an ice cream soda.

Tortoise Beats Hare is most comparable to 1946’s

Northwest Hounded Police, which is possibly Tex’s most successful spin on the formula with Droopy and the convict wolf he’s pursuing.

Hounded’s ending in particular borrows the ending reveal of this cartoon, which shall be explored soon—both shorts revel in the absurdity and difficulty of the pest’s omnipresence, demonstrating the ridiculous lengths the “victim” (Bugs and the wolf, in this case) go to get him off their trail.

Dumb-Hounded, the first Droopy cartoon, likewise obeys by the same setup, but is somewhat less manic in execution than

Hounded.

“Cecil”, additionally, displays a broader range of emotions than Droopy. For example, a smooch on Bugs’ face is his way of a middle finger, a gesture that seeks purely to humiliate. It is doubly so when remembering that disarming enemies through affection is one of Bugs’ trademarks. Echoing the kiss through the graphic of a big, red heart is a great way to instill permanence of the gesture, as well as render it more playful.

More hopping-then-stopping ensues—Bugs’ ego proves to be much more of an obstacle than any amount of tortoises could be. He halts once more to bid so long to “Shorty”…

Though barely a speck of paint on screen, the audience is immediately able to register “Cecil” as the culprit. Inclusion of the bridge not only varies the flow of shots and prevents monotony through the same staging, but also seeks to rub salt into Bugs’ wounds. If the turtle were standing a few inches in front of him, that would be one thing—that he’s so far ahead in the distance is another. It justifies Bugs’ bewilderment and outrage, as there is a considerable amount of distance between the two that absolutely would be confounding if the audience wasn’t privy to Cecil’s clan of doppelgängers.

With the pattern of Bugs dashing ahead, getting his ego checked, and using his broiling rage to propel himself further and land in the same scenario having been firmly established, “Cecil” is the focus of the next scene. That is, the camera is positioned to his height. We are at his eye level, which indicates he’s the main priority. Bugs is just a flash of legs on a screen. Instead, the objective of this scene is to be humored by the turtle’s aside of “We do this kind of stuff to him all through the picture.” Ironically, Bugs himself would repeat that same line in

Wabbit Twouble, which Avery had started.

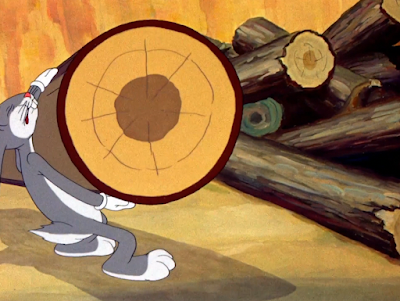

Now, Avery pads some time through and establishing pan gorgeously rendered by Johnsen. We’ve had our share of character beats for the past few minutes—not that they ever get exhausting, but switching to a new point of focus (such as establishing a new environment) is key in ensuring the audience remains engaged. Bugs’ determination to stop Cecil rather than keep trucking forward is at its zenith here: a trench, sealed off with barbed wire, precedes a makeshift barricade of boulders and logs that we find Bugs tending to. Extravagance of his obstacle is one thing, but the implication that Bugs spent the time gathering materials—the barbed wire, the shovel, the rocks, an axe to possibly cut down the trees—takes it to a whole new level. It was that absurdity executed with such an unquestioning nonchalance that Avery excelled at so well in this period.

Sid Sutherland’s animation of Bugs laying the final log is a wonderful demonstration of weight in animation. It seems to be a genuine burden, a sincere struggle and test of his strength (and determination) to even be holding it in his arms. The log itself is handled with careful solidity that contributes to both its weight and its perspective. It looks, moves, and behaves much differently than Bugs, but both remain united enough to give the impression that Bugs is affecting the log and the log is affecting Bugs. A strong sense of visual harmony that is difficult to pull off.

By now, the audience has come to expect any surprise appearances of the turtle. That isn’t a bad thing—that sort of predictability means that Avery’s setup is clear. Rather than chasing the novelty of “Cecil” appearing in front of Bugs, priorities now shift to how Bugs reacts to such a change. How his obstacles grow more and more absurd, how is pride is wounded further and further.

In this case, another kiss on the nose from Cecil prompts Bugs to deface public property by cutting the ropes to a wooden bridge. Convenient for his means to stop his opponent, but an accidental obstacle for everybody else on the planet who relied on that bridge to get to their various destinations.

Animation of the bridge gliding to the edge of the cliff is excellently rendered by Chuck McKimson. It garners similar praises with Sutherland’s handling of the log—the weight (or lack thereof) as it glides through the air is believable; airy, but motivated. An arc guides the movement so that it remains seamless, directed, not jerking around in any one particular direction, and the inkers lining 4/5 of the bridge’s planks all the way through deserve accolades of their own. It’s a maneuver that has plenty of potential to go wrong—jittering, stiffness—but is handled with just the right care.

Ironically, the simple act of Bugs scaling a tree proves to be more problematic. This too is just a minor nitpick that doesn’t impede the clarity of the story nor gag in any way; however, there is a noticeable loss in volume of the birch tree between shots. Its trunk is about twice as wide in the establishing shot than in the close-up, which makes for a brief jump in flow.

Such remains a moot point when the tree serves only as another vehicle to torture Bugs. The turtle’s “Lovely view, isn’t it?” from off screen is particularly reminiscent of both Droopy’s omnipresence and stolidity in his own cartoons—both the vocal direction of “Cecil”’s delivery and the simplicity in which he’s revealed to be hiding above Bugs.

Yet another kiss on the nose, however, is a bit too indicative of emotion for Droopy. Not for the turtle.

Thus, Bugs’ sprinting (which does initially feel more like fleeing than other circumstances) reaches its climax. The dynamic of a million Cecil’s blockading the rabbit has been well established. Avery loved to test the audience’s patience, but usually knew when to stop if necessary. Thus, Bugs refuses to get distracted—both for his sake and for the sake of the viewer. It’s nothing but full sprinting (or hopping, galloping, soaring, what have you) from here on out.

To indicate this, a cross dissolve occurs as most this “montage”. One pose dissolves to the next, Stalling’s musical accompaniment shifting upwards a key to create a climax—these indicate the passage of time, which again supports Bugs’ dedication to running and running only. Another cut occurs to indicate the same idea, though doesn’t have the benefit of a cross dissolve. Thus, it creates a minor jolt, but is excusable and somewhat hidden through the general feelings of adrenaline. Sharp cuts like that indicate suddenness, energy, boldness, which are certainly some of the attitudes adopted by this highlight.

Then comes the moment of reckoning: Bugs’ final stretch across the finish line is portrayed through Rev Chaney in the montage, and hooked up to the following scene by Bob McKimson. Chuckles as he recognizes his victory sound totally genuine—well worn, exhausted, with a desperate twinge of mania on top. McKimson’s animation captures such a crescendo of emotion and relief very well. He even goes so far as to depict where the laughs are coming from; for the most part, his chest is the one heaving, but there are times where it slips down into his diaphragm. An immaculate attention to detail.

“Uh...

heyyy, uh, Speedy!”

Both the audience and Bugs alike should have know by now. It would be all too easy to hand him the victory. Too forgiving of his ego.

There comes a minor air of irony to the appearance of the turtle—at this point, the audience has no idea if this is the real Cecil or not. Could he have been fast enough to cut in front all of those obstacles to personally deliver Bugs’ shame? Is he trusting enough of his cronies to do the favor for him? That sort of dubiousness, no matter how slight, justifies Bugs’ bewilderment and slipping temperament. The lines of reality have been blurred all through the picture, but even the audience is starting to feel those effects, too.

Rod Scribner is the one who has the dignity of animating Bugs’ loss of the same thing. Rather than forking over a single $10 bill, he parses the amount owed in individual dollar bills. Not only is it more practical, seeing as a single $10 bill was a lofty amount of cash to carry back then, it also stings Bugs’ pride further by depicting the amount individually. Ten $1 bills feels like more than one $10 bill. Given Bugs’ behavior throughout the short, it’s surprising that he makes do on his promise—the viewer almost expects him to pull a last minute excuse as to why he “forgot” or doesn’t actually have the amount he owes.

He opts to flaunt his role as a sore loser through the arguably more juvenile route of threats (“An’ I hope ya

choke!”) and mocking gestures.

Scribner maintains his animation as he then depicts more ranting from Bugs—between the gestures, the ferocity in the vocals, and the context leading up to such venting, the performance feels like an accurate precursor to Bugs’ freak-out at the opening of

Tortoise Wins by a Hare. That, too, often regarded as one of the strongest visual performances in a Bugs cartoon, has the courtesy of Scribner’s animation as well.

“

Heyyy… I wonder if I been tricked!”

Revealing a horde of identical turtles would later evolve into the ending to

Northwest Hounded Police, where a synonymous fleet of Droopys taunt the wolf by just existing at all. The execution is just fine here—the audience is obviously privy to Cecil’s schemes, so the reveal isn’t as disarming to the viewer as it is to Bugs. Regardless, withholding the group shot until the last possible moment allows for a greater sense of surprise. It’s not as though there was a shot of the turtles secretly congregating while Bugs’ back was turned. Instead, his feelings of exasperation and bewilderment are again solidified as the audience experiences that same jolt of surprise that he feels.

Here, said turtles proudly hold onto their shares as they mock Bugs through the aid of radio catchphrases. In this case,

Artie Auerbach’s character of Mr. Kitzel, who is the proud source of one of the most frequent radio catchphrases in these shorts:

“Mmmmm…. it’s a possibility!”

For Bugs’ trouble, he receives a 10 Lip Salute as his final act of humiliation. Not even the courtesy of an iris out—just a fade to black for him to stew in. Bugs Bunny, for the first and one of the only times, has lost.

This is a sentiment that has been said before, and will continue to be echoed in many more reviews: it is truly bewildering just how quickly the directors and animators got Bugs’ personality down so quickly.

Of course, this short is astronomically different than the trajectory that Bugs would find himself on as the ‘40s weaned into the ‘50s—these vulnerable asides to the audience, his open threats of violence, his name calling out of aggression rather than good humor, and generally impulsive, emotional demeanor would not become defining traits of his character.

Still, this short is only the third “official” Bugs cartoon made, and it boasts plenty of recognizable aspects of his character. If this short was showed to someone on the street, they would be able to recognize this as Bugs Bunny. He has the voice, the looks, the carrot chomping, the nonchalance when those moments of nonchalance occurred. Certain pieces of character acting seen here—gestures, expressions, movements—would pop up time and time again in many a Bugs cartoon. Particularly those gestures and sensibilities found in Bob McKimson’s scenes.

This may not be the Bugs that is fully embraced by the public, but it is staggering to think of how much has been established in such a short amount of time. Bugs’ vulnerability and thin skin is not a weakness of this cartoon. In fact, it’s a novelty—a great novelty that attracts the viewer. We all know Bugs as the unflappable “What’s up, doc”-ing rabbit; now, see him as you’ve never seen him before—as a raving, conceited loser.

Of course, this short isn’t good just because it’s novel. It is a genuinely solid effort from Avery’s crew, especially at this particular point in time. Animation is solid all the way through, Blanc’s deliveries are in top form, the story is an amusing subversion of the popular fable and the ways in which those subversions are established are even more so. Stalling’s music ranges from comfortably melodic to startlingly human, complimenting actions as menial as the cadence of Blanc’s voice. Avery’s direction is inspired, motivated, solid, indicative of the trajectory he’s headed towards with his later MGM cartoons.

Again, there is a reason why this cartoon spawned a trilogy, a comic adaptation, and a storybook adaptation—and it wasn’t just because it was novel to see Bugs angry. It’s a foundational piece of filmmaking from Avery and imperative in the journey of fleshing out, who, what, when, where, and why is Bugs Bunny.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment