Release Date: April 19th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Kangaroo, Firefly, Skunk), Sara Berner (Receptionist, Hen, Dancer), Cliff Nazarro (Al Jolson)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

A lot has changed within the Avery unit in the span of four years. Animators have been swapped between units, greatly dictating the look and feel of the resulting cartoons. Avery’s comedic sensibilities have shifted drastically—ditto for his artistic priorities and what he wanted out of a cartoon. Per Bob Clampett’s observations, the Avery unit as it stood in 1941 was considered the superstar unit with the studio’s top talent. Not that Avery wasn’t worth the same deduction in 1937, but the rapid expansion of his art direction, his comedy, ever finding and developing his artistic voice truly justified those claims as it stands today; “today” being 1941, in this case.

So, learning that this would be the first—and, lamentably, last—Porky cartoon he directed since those comparatively fledgling years, such a discovery is significant. All of the above changing so drastically in the past four years means that Avery’s approach to Porky will have changed drastically as well, which is a deduction that certainly holds some truth. Contrastly, this short certainly boasts some aspects that could be considered a “return to form” with the character as well. All shall be explored in due time.The final monochrome cartoon of Avery’s career is a formative one. Given the innocuousness of the title, one wouldn’t pin it as one of the most—if not the most—subversive cartoons churned out by the studio. That extends to where it stands as of April 1941 and the remaining filmography that follows.

As many of Avery’s cartoons seem to do, it inspired a number of take-offs, whether that’s two years after the fact with Famous Studios’ Cartoons Ain’t Human—also, coincidentally, the final black and white cartoon of the studio—or 53 with Stimpy’s Cartoon Show. Such again demonstrates not only the staggering timelessness of his shorts, but the excelling level of quality that allows them to be rendered timeless to begin with.

Porky’s Preview is a cartoon within a cartoon. Such marks the final time within the shorts that Porky is cast as a child—an important aspect to note when understanding the quality of his own cartoon (which is to say, not great.) That in itself is why the short—Tex Avery’s, not Porky’s—is so revered; the majority of it is stylized to be crude and juvenile, whether it be the animation itself (stick figures) or the proudly discordant musical accompaniment. Quite the feat to be proud of for Porky, and quite the challenge to have fun with for Avery’s animators and the musicians.

Ironically, the premise and novelty of the cartoon was so potent that the effects of Avery’s crew attempting to pull it back can be felt throughout the short. Not to a real detriment, of course, but the cartoon within a cartoon does start about two minutes of the way in—a third of the short’s runtime. Exposition is necessary, however, and it likewise presented Avery an opportunity to strike some gags unique to the context presented that he couldn’t once the pseudo-cartoon started. Likewise, it proves helpful in easing any potential monotony; the mini-cartoon was a risky gamble, and the attempts to keep it palatable and coherent to the audience are very much felt.

Most—if not all—of the gags in the cartoon’s first portion are related to admission in the theater. “Theater” being a term used incredibly generously; a barn with the proudly juvenile banner reading “PORKY’S PICTURE SHOW” almost draws comparisons to the Our Gang films through its makeshift, rural setting and the endearing hook of little kids (kid, singular, in this case) putting on a big show for a portion of the town.

Such a notion is partially furthered through the patrons strolling into the barn. Chickens, little kids in matching shorts, squirrels, the clientele is distinctly reminiscent of the kinds of background characters that were prominent in the cartoons of the ‘30s. Other characters (such as the receptionist, with all of her makeup) are approached with a comparatively modern sleekness and tightness to both variety and juxtaposition. These differences allow the “theater” to appear more busy and bustling through such variety in approach, but the overarching nostalgia and sense of a throwback still dictates the tone, if only in a broad sense.

The gags therein are about what you’d expect; for example, a mother hen asks for one adult ticket, and three children’s tickets to account for the eggs pressed securely against her rear. Sara Berner flexes her vocal versatility between the nasal, young drawl of the receptionist and the comparatively musty, haughty deliveries of the mother hen. Staging has the receptionist somewhat cut off at the time, the viewers only able to see about the bottom half of her face. That nevertheless doesn’t present a problem—the transaction of her giving the tickets is clear, as is the role she plays. Attention is more importantly shed onto the mother hen and her eggs. Moreover, the composition allows the receptionist to feel taller with how high up she is—such communicates a casual air of authority that tracks with her role of allowing the patrons in.

Meanwhile, the ticket taker serves to do his job. An elderly kangaroo, his design and animation is much more specific and meticulous than how he would have appeared in a ‘30s Avery short. His role as the ticket taker is nevertheless rooted in a philosophy of ‘30s cartoons and the playful juvenility therein—the gag of him storing the ticket stubs in his pouch is antiquated in a manner that is fond rather than archaic. (Eagle-eyed viewers will catch a Porky cameo in the background with a poster of his face on it entitled “Professor Porky”.)

Those thinking that these gags are domestic for Avery would be correct. He proves he has already thought ahead and banked on the audience to be lulled into polite passiveness—that allows for the punchline of the kangaroo casually dismembering a patron to be all the more shocking.

Nonchalance is king, and the mutual insouciance of both the arm ripper and arm rippee allows the gag to revel even further in its absurdity. Sound effects are quaint, animation and the weight of the arm being torn are quaint, reactions are quaint to indicate its business as usual. Avery counts on the audience to do a double take and laugh at how coolly such a violent act is treated—to watch the armless dog scream and panic in hysterics (or the kangaroo to scream and panic) would be too big of a production than what is intended in the tone. Too alarming, and potentially too uncomfortable through the sympathy it elicits with such panic-stricken reactions.

Instead, the Avery of 1941 was still a subscriber of keeping his cool. Playing things straight—or, in this case, drastically underplaying them—to embrace the guttural double-take felt by the audience that seems to elicit a more powerful feeling of surprise than if their notions were justified through hysterical reactions on-screen. The result is doubly effective with the bucolic domesticity of the prior scenes in mind.

A firefly theater usher falls into the sort of domesticity that offered such an effective juxtaposition to the prior gag. Still, like its companions, it proves to be harmless—the light moving as the bug shifts is weight proves to be accurate, and offers a visual flightiness that is well matched by Stalling’s tinkling orchestrations of “The Umbrella Man”.

A shift back to the receptionist indicates a change in tone; mainly from the manner in which her customers perform a wild take and flee off screen. It’s a maneuver that begs for elaboration, and elaboration occupies more time than animating a simple punchline (such as a firefly using its light as a flashlight). Amusingly, the wide-eyed take from the tall dog is particularly reminiscent of Avery’s drawing style. Tall, conjoined eyes, elongated muzzle, and generally elastic, limber body construction all feel like a product out of his MGM cartoons, where his artistic sense of style were more pungent.

Enter one skunk. The receptionist suddenly equipping herself with a gas mask speaks for itself—that in itself isn’t as amusing as the implication that she has it stowed away just for situations like these. It’s clearly not her first encounter with a skunk.

“Hey, how much t’ go in?” Bugs Bunny-esque voices have become routine in Avery’s cartoons. Here, the skunk bears the honor of touting the wiseacre, nasal strains for this particular cartoon.

“The chah-ge is five cents, ple-uh-se!” Excellent sound design by muffling the receptionist’s vocals.

What comes next is painfully obvious. So much so that it serves as the entire point—after the skunk laments on his mere “one scent”, he turns to the audience, tilts his head, and declares in a startlingly nonchalant, muted tone: “Get it?”

It’s the concession that the gag isn’t funny that makes it so funny. The shift in his voice register carries a lot of weight regarding the success of the execution; it’s stupid, it’s simple, and Avery was a master of stupidly simple. His aside almost serves as a companion piece to the kangaroo dismembering his customer—a commentary on how Avery recognizes the quaintness of the scenario and reassuring the viewer through winks and grins that this isn’t permanent. Subversions are on the horizon.

Following the skunk into the next scene indicates a permanence, a story point of sorts. He’s important enough to constitute numerous scenes, whereas all of the others have only had the benefit of one; perhaps this joke cracking skunk offers more than meets the eye.

“Lessee… 'dere oughta be some way a’ gettin’ in dis joint.”

A door clearly marked “EXIT” proves to be the solution to his problems. Though the screen dissolves to the interior of the barn, Avery communicates the sense that this won’t be the last time we see the skunk.

Porky, however, takes priority. The childish swagger as he marches on stage—even at a distance—is fantastic. Perhaps these observations are largely swayed through the triumphant orchestral fanfare heralding his arrival, but his walk as he sways to and fro drips with pompousness and conceit. Not out of ego, but out of sheer innocence. Obviously, putting on his own “picture show” is a very big deal to him. He has every right to be proud at seeing his vision through, even if his vision is much more quaint than he lets on. It is. After all, this is a random barn—not Madison Square Garden. The pride in Porky’s footsteps and mannerisms, however, would have you thinking otherwise.

Virgil Ross has the honor of introducing the “new” Porky under Avery’s vision. A casting choice that is earned and makes sense, considering Ross had likewise been animating Porky for Avery ever since the conception of his unit. It’s certainly fascinating to compare the difference four years makes: his ears are no longer folded at their tips, as was often a distinguisher between Avery’s pig and the other directors, his large pie eyes have been shed for a much smaller alternative who are spread further apart on his face, his proportions are less even and streamlined to look cuter through a more organic distribution of weight. In less expatiating terms, he’s adapted to the current style of the times without missing a beat.

“Eh-hiya, guh-ge-eh-gang! Ehh-nuh-nee-eh-now if you’ll all be eh-keh-ehhh-quiet, weh—heh, we-we-we'll start the show.” It should be noted, of course, that nobody is even talking to warrant such a disclaimer. To Porky, that’s completely irrelevant. He’s playing the role as the emcee, and in his mind, emcees tell people to settle down and be quiet, so to assert that he’s a proper emcee, he must do the same. There’s a very clear, endearingly juvenile string of logic that he follows.

Mel Blanc’s deliveries and Virgil Ross’ attentive character acting couldn’t be married more perfectly. Vocal direction for Blanc is, likewise, some of the most excellent, natural and charismatic for Porky to date—the awkward, semi-modest, almost-but-not-quite nervous chuckles, the pauses, the reserved intonation all read incredibly organically, yet not to the point of excessive subtlety.

Likewise, Ross is perfectly able to capture the childlike unprofessionalities that give Blanc’s deliveries legs. Eye contact is seldom maintained, and idle gestures such as modestly scuffing his feet or flicking something off of his knee both succinctly capture the restlessness that embraces every child and could possibly place a hinderance on their stage presence without their knowing or caring. Such gestures likewise indicate a sort of humility—it’s clear that he isn’t very used to speaking in front of crowds or being in the literal spotlight. He doesn’t seem nervous or terrified by any means; only unaccustomed.

His words, likewise, don’t carry the same humility as his gestures. Again, not out of conscious conceit—just that this is new to him and he deserves to take up his moment in the spotlight.

“I, uh, heh heh…” Again, the excellence of Blanc’s organicism in his deliveries—especially with the chuckles—cannot be understated. “I-I-I drew this cartoon all behh-buh-beh-ehh-by myself, heh…”

“But eh-shucks, it wasn’t hard ‘cause—heh—I’m an artist!” One can imagine that line got a lot of laughs out of the artists during studio screenings. If only it were that simple; Porky’s not so humble bragging is almost aspirational. We should all be so lucky to live a life as simple as his.

“I-I-I hope ya like it.” Not that Porky intended for his previous words to sound insincere, but this statement certainly does seem to be the one rooted in the most earnest.

As is the case with him walking off with polite applause, only to remember his manners and hawk an obligatory “Ehh-theh-thank you!” in return. It’s such a genuine beat of character acting that even afflicts his adult self; he repeats the same routine in You Ought to Be in Pictures out of the same innocence and goodness of his heart. Almost a compulsion, it’s a very telling gesture in that he feels the need to be so polite. As though he would be scolded by his mother (or, in this case, an audience member) for forgetting… even if the applause that filled the screen served as a reassurance in itself.

And, with the parting of some tattered curtains, squeaking and jolting in their separate ways, Avery is finally able to throw everything this short has led up to out the window. This is not a saccharine, cutesy pastoral jamboree that tickles the innards of audiences from sea to shining sea. It is a ripping satire of the medium of animation, which certainly includes Avery’s own work. The opening two minutes being as domestic and innocuous as they are prove to be fixtures in the parody’s success; it seems to come out of nowhere and bludgeon the audience over the head.

It is this moment when the projector winds up, images begin to flicker on screen, a discordant whine of a musical backing track pierces the ears of audiences both fictional and living that is my favorite part of the whole cartoon. Seeing Porky’s drawings slither onto the screen—first at enough of a distance for the viewer to sexing guess themselves and ask “No, that can’t be right… can it?”—is an unparalleled surprise through the crudeness in his draftsmanship and the positively contagious mischief seeping out of Avery’s directing that the cartoon doesn’t seem to live up to as it stretches on. Reasons as to why will be explored shortly.

For now, soaking in the hand drawn crudeness of Porky’s hard work and the triumphantly cacophonous arrangement of “The Merry-go-Round Broke Down” takes priority. The entirety of the cartoon as it stands is a meta commentary, but this introduction even moreso; the background arrangement being the song to grace every single Looney Tunes intro that brandishes Porky’s face indicates a playful self awareness from Porky rather than Tex Avery. While it’s not by any means meant to be the takeaway, it does implies that he’s wise to his own stardom and role as a cartoon character—he knows these cartoons begin with that music and his face. That in itself offers an entirely new layer of parody that enriches the end product of this cartoon and strengthens its case as to why it’s so strong.

Additional parentheses as Porky provides his own director’s commentary excel in their stupidity. “(Artist)” and especially “(Funny)” are completely arbitrary addendums, but addendums that are rooted in believability through Porky’s juvenility. It demonstrates his observation skills—he knows what’s funny! He knows he’s an artist!—and how he revels in the opportunity to show off what he’s learned. This too seems to imply that he’s spent plenty of time laboring over what’s funny and what isn’t; he’s seen enough cartoons—potentially directed by Avery himself, given that it’s an old pet gag of his—to know that arbitrarily elaborate fractions (like 6 7/8) is funny. He seeks to demonstrate the extent of his scholarship to the audience and hope that they, too, will be just as impressed as he is through his own awareness. It does certainly evoke strong feelings of endearment.

The title cards are the best aspect of his cartoon. Namely because they are the most rooted in authenticity and believability, whether through the crudeness of his penmanship or the amusing display of exuberant, innocent conceit mentioned above. The viewer can easily picture Porky leaning over a table, scrawling out little self portraits and chuckling to himself about what a great artist he is. Namely because most—if not all—of the audience has been in his position at some point in their lives.

However, and rather ironically, the “funny pictures” themselves prove to be a vice for the cartoon. It should be reaffirmed that the following criticisms are mainly a product of obsessive nitpicking—this is a fantastic cartoon and one that is very important through its lack of humility and obliteration of metaphysical boundaries. It is a wonderful representation of what makes Tex Avery Tex Avery, and it is by all accounts competently directed, drawn, and scored.

Yet, the cartoon is almost too competent; the drawings on screen are stick figures, remaining true to Porky’s artistic vision, but they are animated with aspects of the 12 Principles that no 7 year old would be able to master. Compared to the title cards and backgrounds (which, should be noted, a caricature of Henry Binder stands as the enigmatic “you” introducing the Circus Parade segment), the drawings are polished, clean, and competent. They are animated in perspective, motions ease in and out, proportions and details are consistent with one another, and read exactly as they are: a bunch of trained, seasoned professionals trying to unlearn years of experience to mimic a child’s art style. Such is a mission that seems to be much easier said than done.Perhaps some of it is rooted in necessity. This was an absolutely groundbreaking cartoon for its time, and still elicits the same surprise and laughter 82 years later. Thus, Avery had to be careful in ensuring he didn’t completely lose his audience and go in over his head. Perhaps the viewers would have been confused or dissatisfied if the drawings on screen were true, genuine scribbles that moved and behaved as poorly as they looked. Perhaps distributors would refuse to show it for the same lack of understanding. Perhaps it would read as boring and repetitive if chained to such incomprehensibility. Strictly pertaining to the physics of the motion, this “cleaner” alternative certainly is more interesting visually, though the sleekness of the designs remains somewhat off-putting.

Carl Stalling and Milt Franklyn’s music falls into the same category. They do a great job as is; it is incredibly difficult to play badly and still sound somewhat coherent or appealing to the ears of the audience. Yet, discordant and childish as the music may sound, it is still orchestral and still beyond feasibility regarding Porky’s talents. Harmonies—broken as they may be—are still layered on one another, there still proves to be a variety in instruments, there still proves to be a lingering hint of perfection that Stalling and Franklyn are unwilling or unable to part with, just as the animators are with their drawings.

There is a certain suspension of disbelief required in viewing the bulk of this cartoon for the reasons above. In any case, the positives vastly outweigh the negatives, and the decisions made regarding this sheen of cleanliness—even if we don’t exactly know the case as to what these decisions truly are or why—are understandable.

Nevertheless, one of the successes of this short is again through Avery poking fun at himself. A handful of Porky’s sequences showcase gags that even by 1941 were considered old hat—however, many of them are gags that have been found (and often would continue to be found) in Avery’s cartoons. For example, an incongruously diminutive elephant amidst a string of its larger cohorts; it’s a gag that dates back to even the earliest Warner shorts and beyond, which is why it is included—Porky finds these surface level gags funny and novel, when more seasoned professionals would regard them as trite or hacky instead.

An employee of the department of sanitation following the parade after a beat indicates Porky is even fond of bathroom humor; it does, of course, bear mentioning that he would make a similar wisecrack regarding a somewhat synonymous situation at the end of Drip-Along Daffy. Old habits die hard.

Henry Binder’s likeness continues to pepper the screen as the next “funny picture” ensues. One has to wonder what his reactions were upon seeing the cartoon for the first time—this certainly wouldn’t be the first nor last cartoon to caricature him, as he proved to be one of the most frequent cameo-holders in the shorts, but the “intimacy” inherent to this particular scenario certainly does make it more interesting.

A train conductor plowing along in his wonky, simple train is more successful in achieving the crudeness this short begs to channel—it remains elaborate beyond solid belief, but the design of the train with its misshapen wheels and rectangles, the swirls representing the smoke, and the whistle emanating “TOOT”s that zip along the screen in conjunction with “California, Here I Come” prove to be comparatively easier to digest. The “TOOTS” in particular are a great inclusion not only because they are representative of a 2D drawing, onomatopoeic words hanging in the air, but because trains—of course—do not go “toot”.

This too spawns another polite self-riff on a tried and true gag—a vehicle, animal or person rolling over hill and dale remaining the same height the entire time, with only a pair of legs or wheels or whatever else extending to meet the dips below. Here, the backgrounds prove to be the main attraction, approached with a meticulous authenticity that spans from how the trees and houses are drawn to the crude ways in which the pencil moves.

Cartoons Ain’t Human, it’s worth mentioning, would borrow condensed inspiration from this same gag in a short that already owes its entire existence to this cartoon.

Also worth mentioning is yet another Henry Binder sighting within the background’s void. The strongest part of the sequence stems from the background coming to a complete end—while the details may stop, the train continues to cycle over invisible hills. A giant “END” sign amusingly supports the argument that Porky merely got tired of drawing out an entire background pan layout and decided to cut some corners. No doubt, the layout men and background artists of these shorts wished that they, too, could enlist in the convenience of an “END” sign.

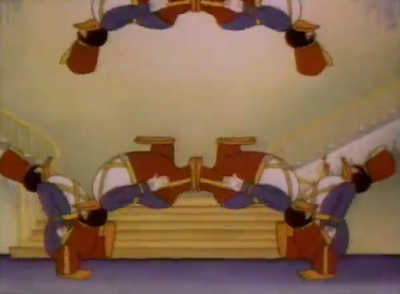

Delegating a sequence to soldiers marching in perspective elicits similar critiques regarding the “professionally” (if one could call it that) of the animation being too asynchronous with Porky’s skill level, but remains much more entertaining than distracting. Stalling’s kazoo cover of “Frat” proves infectious in its joy, as the viewer can easily imagine the orchestra trying and failing not to laugh during rehearsals. It permeates such a simple yet resounding feeling of utter joy, which is true of the whole cartoon. That in itself is much more important than scrutinizing Porky’s superhuman understanding of animation physics at age 7.

Beyond a quick highlight demonstrating a tall soldier repeatedly kicking a smaller soldier in the keister, this segment likewise offers a commentary on some gags found in Avery’s older cartoons. Soldiers traipsing vertically along the screen proves to be a direct takeaway from The Penguin Parade in 1938. A relatively recent effort, all things considered; this certainly offers interesting insight as to what Avery regarded as tired or uninspired or played out.

One of the most interesting takeaways again lies in the music; a human voice can be heard humming “bum-bum-bum bum bum,” in tandem to the music, piquing curiosity as to whose voice it could be. Such a small, insignificant detail that embraces the kitschy, handmade appeal of the cartoon within a cartoon.

Elsewhere, a horse race offers an avenue for a joke that the Warner guys held onto for years. Animation of the horses and jockeys is again too sophisticated for Porky’s standards, the variation in timing and spacing of the drawings as the horses launch at differing speeds being too complex; all of that is nevertheless visual fluff to accompany the brewing punchline:

Bing Crosby’s horse coming in last. A continuation at Crosby-themed jabs that has been studio tradition since 1936 (1932, if one were to count Crosby, Columbo and Vallee) that resulted in two failed lawsuits from Crosby himself.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment