For the second time, Clampett is able to indulge in the freedom of color cartoons. This occasion would mark the last time such is the case with his regular animators—after this, he’d switch back to doing black and white shorts. Any color opportunities that arrived after were with a new unit of animators, finishing up the work left behind by Tex Avery as he made his leave. This would eventually become Clampett’s permanent unit of animators, with his old unit helmed by Clampett unit animator Norm McCabe.

When regarding these cartoons, it’s all too easy to feel that everything about them has been discovered and scrutinized. Some of that is true to an extent; these shorts are 60, 70, 80, 90 years old, which offers a generous amount of time to historians to make further discoveries, deductions, and place the puzzle pieces together. So, when a new major discovery is unearthed, it certainly isn’t taken for granted.

Farm Frolics, in all of its perceived innocuousness, is one of many shorts who once touted an enigmatic air of mystery. Not only was a cut gag from the cartoon found and restored, but the original titles and opening sequence once excised by the Blue Ribbon reissue titles as well. A big thanks to David Gerstein for discovering the print at the Library of Congress—it should be noted that he was also responsible for finding the once-cut ending to Hare-um Scare-um as well. If we’re lucky, more of these lost titles (and occasionally lost endings) will surface in the coming years. Hopefully in time for this blog to document them.

Thus, we are left to luxuriate in these newly unearthed titles. Granted, the copies circulating around beforehand did have the opening chorus of beneath the Blue Ribbon title, which is an exception more than a rule. Main differences preside in seeing the credits and a hand wiping them away on a drawing board, as well as the chorus playing to its full extent. Previous copies had Robert C. Bruce’s narration cutting in on top of the chorus, encouraging a slight dissonance that doesn’t reek of revisionism more than an odd directorial decision.

Nostalgia seems to be the reigning tone of the opening; “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm” was a song that was considered old hat even in 1941, adapted from the 1903 children’s novel (and more memorably adapted on film in 1938 with one Shirley Temple); that, in conjunction with the throwback of a hand sketching a cartoon to life both collaborate in dictating a tone of fond remembrance and quaintness.

Establishing such regression is not necessarily to encourage it; rather, it begs to be shattered. Lure the audience in with warm idyll, only to warp them into screwball gags and proudly uphold the Looney Tunes name.

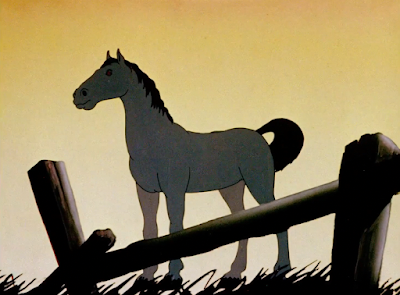

To Clampett’s credit, he maintains his sense of restraint for about a minute into the cartoon. Bruce gently guides the audience into the cartoon, leading them to examine a show horse and its various tricks. The horse is approached with necessary stolidity, reading as a regular, domesticated horse first and foremost over a semi anthropomorphic hybrid. Its hind legs are inked a slightly lighter shade of gray with a yellow tint to simulate a depth of focus; eagle-eyed viewers will note that said legs are on a separate cel layer than the rest of its body. A commendable attention to detail that likely would have been overlooked if the short were in black and white—they do it because they can.

“First, let’s see you do a trot.”

Horse obeys. Mechanics of the horse’s run cycle are impressive, as there is a physical shift in motion and weight during the segue from a trot to a gallop. Compare this horse to the one in Slap Happy Pappy—while still solid, the horse here is much more literal and realistic in its adaptation. Such allows any potential comedic antitheses to thrive and read stronger.

With each run the horse performs—a trot, a gallop, a canter—Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment adopts a different song that perfectly matches the cadence of the horse’s run. “The Old Gray Mare” has a slight swing at the end, but remains steady and leisurely. “Light Cavalry Overture” is a bit more imposing and brazen, indicative of the rise in intensity but still pleasant overall.

And, lastly, “I’m Happy About the Whole Thing” is full of pep and energy—such is necessary to match the Eddie Cantor caricature that morphs on-screen in accordance with Bruce’s directions for a canter. Thus, the pandora’s box of screwball hijinks is thereby initiated, confirming any suspicions as to how stolid this cartoon will be. The answer, of course, is not very.

While the absurdity of the gag is enough independence in itself, offering an avenue to shift focus right there, Clampett remains dedicated to the gag. Instead of asking how that’s possible or what on earth is going on, Bruce merely growls “That’s enough of that,” his tone surprisingly restrained given the circumstances. The viewer doesn’t get the indication that this is the horse’s first instance of such a performance.

Likewise, it doesn’t seem to be his first scolding, as he obeys with a sheepish grin. Added humility makes the gag funnier, as though he knows it’s not something he should do, but just can’t help himself. An unbridled merriment that is shared with the audience. His stature is considerably less formal and rigid, more in tune to the typical malleable construction of animated horses to be more indicative of his expressions and emotions. The seal of stolidity has been broken and refuses to be corked; even if the horse isn’t able to dance and sing, upholding a comparatively looser, cuter, more mischievous design still remains a contrarian piece of activism on his part.

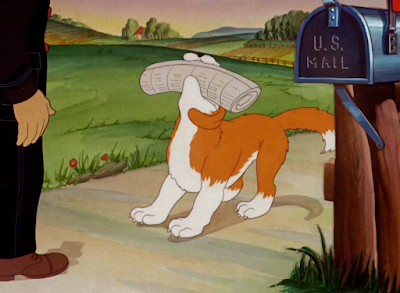

“Here, we find the farmer’s faithful old watchdog.”

Dick Thomas supplies his handiwork for the short’s background scenery. A few scenes are particularly reminiscent of his work in the 1944 Frank Tashlin cartoon, The Stupid Cupid, whether it be through color choices of the sky or patterns in his brushwork. A mainstay of the Clampett unit, a novelty persists in seeing the ways in which he chooses to indulge in color. Atmosphere is not lost within the shift from black and white to Technicolor, as he is still able to keep his values bold and contrasting, still able to construct a cozy atmosphere, still able to inject dynamism into his work. Here, having the tree frame and arc around the dog is a particularly attentive touch—beneficial in both establishing a warm atmosphere and guiding the audience’s eye to the dog. Much like his work in the monochrome cartoons, the tree retains bold, dark values in the foreground to pop against the neutral softness of the background.

In other words: it looks good.

“Though he is no longer very active…” Bruce’s narration is momentarily disturbed by a yawn, supporting the dog’s growing age and inactivity—“… he still does a few little odd jobs around the house.”

One of those being to grab the newspaper; with the whistle of the mail truck off-screen, the dog sheds his own stolid exterior in the same manner of the horse as he perks up. His head is more circular, his eyes wider and caricatured. Addition of his eyelids, no matter how slight, still gives him a somewhat worn appearance to stay loyal to Bruce’s narration. Regardless, the shift in demeanor remains effective and pungent, as he’s still got enough spryness in him to eagerly pursue his chores.

Notes of youthfulness are further conveyed in his departure for the truck—barks are abound, the rug on the porch upturned to indicate his zeal. It’s a physical indicator of his excitement, a creative way to demonstrate his newfound energy in ways other than barking and running. An upturned rug indicates that “order” has been disturbed; said order is not a priority when under the intoxicating arrival of the mailman. Stalling adopted a peppy, high pitched flute motif of “Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone” does wonders in cementing the sudden shift to his fervor.

Having the disembodied mailman playfully toss the newspaper into the dog’s mouth cements further notes of nostalgic idyll. So many dogs in cartoons are pinned as the vengeful rival against a hapless mailman desperately trying to make the rounds. Not this one, though. That’s a vision that directly contradicts the pastoral setup and all of the elements therein. Such exposition is certainly headed to a punchline, but the mailman seems to only be a bridge rather than a target in orchestrating any gags.

Focus belongs solely to the dog, whose mechanical rotations as he skids to a stop again elicit a laugh through such exaggeration. The motion itself is rigid and stiff—a good thing, as the movement is meant to seem uncanny and almost robotic. It’s another manifestation of his eagerness to indulge in the pleasures of farm life. He’s so excited over retrieving the paper that he can’t even skid to a complete stop, much less put a stop to his aimless, robotic rotations.

.gif)

Laying the paper onto the ground and flipping dutifully on top of it heralds the most amount of anthropomorphism and caricature maintained by the dog yet. Like the horse, his transformation to sentience is now complete. Bright eyed, ears perked, legs in the air, the dog is a certified denizen of a Bob Clampett cartoon, exuding plenty of zeal that is proudly incongruous to the exposition established moments prior. His excitement isn’t out of a desire to please his master—it stems from the pleasure of indulging himself in the newspaper. More specifically, the Sunday funnies.

Fans of Clampett’s cartoons will immediately recognized that the dog’s dopey declaration of “I can hardly wait ta see what happened ta Dick Tracy!” would be reused verbatim in his magnum opus, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery a mere five years later. Outside of Clampett’s directorial involvement, that can also be attributed to Warren Foster, who bears a writer’s credit on both. Indeed, Daffy’s own pose as he hovers over his beloved comic book is synonymous to the dog’s here. The main difference resides in the years of experience that followed between the gap of these two cartoons, allowing Clampett to embrace and inflate the joyfulness and sheer mania of the situation.

A return is made to a more temperate scene as the audience views some “cute little piggies playing in the mud.” Or, at least, such is intended—there appears to be a slight splice that momentarily cuts off the end of Bruce’s narration. The intent remains clear nevertheless.

That isn’t as disruptive as the purposeful betrayal to Bruce’s words: said cute little piggies are instead gathered feverishly around an alarm clock hanging by a string. As a testament to their fixation, they even bump some of their litter mates out of the way from seeing the clock—just as one would do when struggling to find room during feeding.

“Oh well,” remarks a befuddled but dismissive narrator. Thus, the frequent point of return throughout the cartoon is established. This won’t be the last time these enigmatic pigs are visited.

John Carey handles the following scene of a mother hen doting over her eggs, which are soon subject to danger thanks to a conniving weasel. While the scene could feasibly save some time by cutting directly to the weasel peering through the window, the addition of the mother hen is helpful in injecting pathos. Crimes of weaselry are inflated to seem more despicable when knowing that a mother’s love lies behind (and on top of) those eggs. Ditto for Bruce’s comments on the happy family.

Clampett does a great job of building suspense; Carey’s menacing animation, Stalling’s grumbling music score, and Bruce’s anxious play-by-play all meld together to transform the weasel into a threat and the eggs a target. Rapid camera movements are particularly successful in their creativity, zipping around with a brevity that is reminiscent of eyes darting around in trepidation. It gives the scene more movement and dimension, as well as even further pathos. The audience shares the point of view of the camera. They are intended to be the ones looking around helplessly as a potential tragedy unfolds.

Both Clampett and Carey take things slow to milk the drama. Whereas a real weasel may just tear into the eggs then and there, unbothered by the hay “blanket” covering, our fictional weasel takes the time to peel away the only layer of protection the eggs have. Movements are slow and gradual to embrace as much suspense as possible. The outcome is successful—especially given the appeal and solidity of Carey’s drawings.

Such laborious setup is vital in establishing the surprise aspect of the eggs hatching, thereby scaring the weasel out of his wits. Just as the weasel did, the audience becomes intoxicated by the crawling suspense. Such a low, rumbling music score, the furtive lugubriousness of the weasel’s movements, and Bruce’s hushed observations amalgamate to form a quietude that is violently thrust out of the scene through the mere synchronized pop of some chicks. Glowing line effects detail the overshoot of the eggs hatching, a graphic, traditional touch that pronounces the impact perfectly. Such an additional pop justifies the startled reactions of the weasel.

Killed by cuteness, the weasel struggles to regain his wits. His shuddery “Don’t ever do that!” is a direct takeaway from comedian Joe Penner—such a recitation of celebrity catchphrases gives the indication that it’s okay to laugh, the tone has permanently shifted to one that is lighthearted and mischievous.

That, too, is validated through the playful tittering of the innocent chicks. Their dot eyes render them more akin to toys, injecting a different kind of pathos. There’s the route of drawing them with regular eyes, therefore humanizing them and drawing more sympathy. Dot eyes are more synthetic, again akin to a toy or object rather than a living being, but that in itself introduces its own unique pathos through such a shorthand indication of cuteness. And, of course, the weasel’s exhausted expressions as he catches his breath are just as appealing; coloring his face a sickly green serves more as a shorthand for fear rather than logical reaction, but that is by no means an issue. If you can do it, do it—such is the motto seemingly adopted regarding the restored freedom of color cartoons.

Dick Thomas’ backgrounds are offered a spotlight in the introduction of bird life; a pond shrouded by dense, twining trees, yellow sunlight pouring through in a symmetrical arc within the trees all feel like something out of Snow White. Given Clampett’s love of the film, occasional making references to it throughout the entirety of his career, such comparisons don’t seem completely unfounded. Even if the film itself isn’t a direct influence, the Disney idea of tranquility is.

Clampett continues to do a fine job of encouraging an organic pacing and exploration style. Amidst Bruce’s orations about birdlife, he suddenly cuts himself off by saying “Look up there!” The camera obeys his wishes, panning up to a cluster of trees that are decidedly birdless. Thomas’ painting style here is particularly reminiscent of his work in

Stupid Cupid, albeit a bit looser and less refined.

“No no, over to the left.” Camera again obeys, settling on a baby owl within the hollow of the tree. It’s such a menial little addition, but adds so much in making the short feel more immersive and engaging by proxy. Viewers are made to feel as though they are actually experiencing the events of the cartoon in real time, standing next to the ethereal narrator rather than listening to a narrator patronize them from their seats.

Slow, almost mournful hoots emanate from the little owl’s mouth…

“

Whooooo’s Yehoodi!” Upon his

Jerry Colonna impression, the owl perks up, a glint in his eye and a grin at the camera that fades just as quickly as it sparks. While the reference may be lost on audiences today, the shift in demeanor from the owl is still enough to spark interest.

Dissolve to more domestic matters: a pair of lovebirds constructing their nest. They alternate in their string-n-straw fetching, a methodicalness that is quickly lampooned as their interchanges accelerate in momentum. Quicker and quicker, they fly back and forth, Bruce’s narration barely able to catch-up. Timing of the altercation is sharp, as the birds seem to overlap with themselves at the climax of their nest building. Bruce’s feverish narration does a fine job of giving a permanence to the caricature of their work ethic.

Thus, a fully formed cottage materializes: a window planter, a chimney, even a weathervane are all great touches that are purely decorative. Twigs arranged in the form of a barebones shack aren’t enough. Windows with glass panes, varying structures of wood, a brick chimney, a metal weathervane, and so on are all pieces of vanity that indicate humanity first and foremost. The literality of their abode is cemented through the sign proudly declaring “APPROVED BY F.H.A”—the ultimate endorsement.

On the topic of

The Stupid Cupid, a synonymous gag would be reprised to greater brevity. Warren Foster bears a writing credit on that cartoon as well, thus justifying the similarities.

Here, however, Clampett indulges in the details just a bit more. The gag is topped off with the birds occupying their new home, warbling a disingenuously off-tune, squeaky chorus of “

Home Sweet Home”. A caricature of saccharinity that finishes the asinine exactingness of their operations. Not only have they built a home, and not only is the home picture perfect, but their home life as well—everything is squeaky clean and orderly. Too much so.

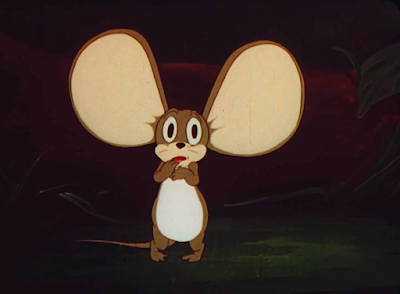

Field mice in the woods are Clampett and Bruce’s next topic of observation. More specifically, one particular case who boasts ears that are almost as big as he is.

Bruce’s observation of “Say, he seems to be a bit worried” doesn’t carry much water if it isn’t accurately reflected in the animation. Thankfully, the mouse’s anxious character acting is crystal clear. The animators do a fine job of conveying his hesitancy and suspicion without defaulting to more obtuse stereotypes or tropes—his acting is much more subtle, following the route of wide-eyed glances, fiddling with his lip, and retaining a hunched, closed off posture. He doesn’t jump at the presence of the narrator or shudder—in spite of his apprehension, an innocent inquisitiveness prevails.

His answer regarding Bruce’s equally curious inquiries is on the nose, but harmless: a restrained “I don’t know, doc,” marks the first utterance of “doc” in a Clampett cartoon—a testament to Tex Avery’s ever ethereal presence. Meanwhile, the punchline of “I... I just keep…

heeeeearing things…” is made amusing through the mouse’s almost understated delivery. His voice warbles, but the line itself is approached with a stolidity that gets a laugh; it’s as though the audience is meant to laugh at the predictability of his answer more than the answer itself. Of course he would say that.

Stalling’s ironic wah-wah trumpet sting as the scene fades to black seems to justify the intended sardonicism.

Regarding irony, the fate of this next sequence is the most ironic of them all. Outside of the butchered titles, this scene is of the most interest regarding the recovering of lost footage: a grasshopper preparing to spit its tobacco-like substance. The setup is nice and clear; Bruce wastes little time, introducing his next factoid with “As you all know,” to keep things moving.

Grasshopper/tobacco gags aren’t new to animation.

Pop Goes Your Heart, for example, features a scene where a father grasshopper attempts to teach his little ones to chaw ‘n spit their tobaccy to little success. Exposition isn’t the priority here so much as the expectation of the outcome. We don’t need to know how they spit—just that they do spit. A flower bulb shaped like a spittoon serves as another clever device to set up and clarify the gag.

So, the joke being that the grasshopper is barred from performing his trick (“Sorry, folks! The Hays Office won’t let me do it!”) is made twice as funny in a modern context knowing that he was absolutely correct. In pure Clampett fashion, the skins of the suits seem to have been rubbed just a little raw.

Back to regularly scheduled, uncensored normalcy. Introduction of an anthill prompts a gag that has now been reused thrice within these travelogues—the language of ants and how they call out to their loved ones. Newfound independence regarding color is particularly noticeable in this scene through the intricacy of the coloring on the ants—not only are they made up of red, blue and black segments, but they are even regarded with a flourish of shading. A decorative touch that almost certainly wouldn’t have been accounted for if the short were monochrome. Again, the ant can have blue legs because it has the freedom to have blue legs.

To Clampett’s credit, he does place a more personalized spin on a frequently reused gag. Instead of an abrasive, masculine shout of “HEY, MABEL!” (as is the case in both

Believe It or Else and

Wacky Wildlife), the femininely voiced ant shrieks for her young one. This time, reuse is native to Clampett: her “

Heeeeeen-RYYYYYYYYYYYY!” is again a spin off of the introduction to

The Aldrich Family radio show, only just lampooned in Clampett’s

Goofy Groceries—the short preceding this one in his filmography.

Henry’s “Coming, mother!” is even the same soundbite from

Groceries, provided by the budding talent of Kent Rogers. It may be easy to knock on the repetition of the gag now with the availability of these cartoons, but audiences in 1941 likely wouldn’t have known that the ant or Aldrich Family gags were both reused material.

Perhaps most intriguing from a historical standpoint is the visual topper that follows: Henry’s butt-flap, exposing his proudly human skinned rear, falls down as his mother whisks him back into his home. Butt-flap gags were a common staple of the earliest Warner shorts; such came to an end upon the crest of the Hays Office.

Clampett had mentioned in his interview with Mike Barrier that one of his tactics for being able to sneak such risqué content through was to place deliberately objectionable gags in his shorts that were sure to get stricken down by the censors. Thus, the other gags (such as the exposed butt visual here) are tamer in comparison and thusly left alone. It’s not to say that this was his exact line of thinking regarding this cartoon in particular, but Mr. Grasshopper’s sacrifice is certainly more illuminating upon retrospection.

Back to the piggies, whose revisiting is painted as a happy accident rather than purposeful check-in. Bruce’s narration on the business of the farm does not relate to their needs or presence in any way—yet, given that he’s here, he opts to switch gears and comment upon their fascination with the clock once again. Still, both he and the audience are left with no answers.

To distinguish this visit from the last time, Bruce directly grabs their attention. Asking why don’t they play instead grants him with a unanimous, jolly shake of the head no; still not enough to parse together what’s going on, but illuminating enough to hint towards the audience that they will find out eventually. Such deliberate opposition doesn’t go unexplored nor unanswered.

“Oh well. Suit yourself.”

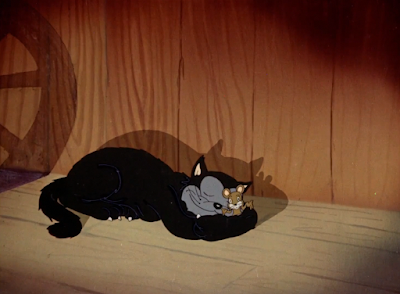

Moving forward, the camera adopts a focus on symbiosis between cat and mouse. Bruce arouses intrigue by labeling the ordeal as “strange”—strange things are different, and difference things are interesting, so surely the audience is curious about how such a relationship could ever happen.

Even the narrator is at a loss of an explanation. So, rather than providing his further musings, Bruce decides to interview the mouse. Similar to the dog and the horse, the mouse’s face morphs into fully realized anthropomorphism in real time as he gains further awareness of the camera. His construction is much more squat and caricatured than his initial position.

“Tell me—is it true that the cat takes good care of you?”

Each answer of the mouse is conveyed through a whining slide of the violin that seems to say “Mm-hmm!” It’s a clever approximation that is both astutely caricatured and mindful of the audience’s attention. Bruce asks a question. The mouse nods in affirmation. Such repetition isn’t grating, but could use a lift in ensuring the audience falls willingly into the pattern rather than be bored by it.

“Now, before we leave you, is there anything you would like to say to your friends in the audience?”

Another sleepy nod. The audience braces for a saccharine recitation of good tidings, or to brave a moral about how you never know who you will wind up being friends with.

A deep throated bellow of “

GET ME OUT OF HERE!!!!” is the more Clampett-ian option instead. Just as it did in the scene where the eggs hatched and scared the weasel, the camera suddenly jolts towards the mouse to surprise the viewer further. It isn’t a measure of clarity, as the mouse is perfectly visible from where he stands (and the scene cuts to a new layout immediately after.) To Clampett’s credit, he’s done a fine job of making his camera moves feel purposeful and guided in this cartoon—such is not always the case. Here, the maneuver is quick and abrasive enough to instill a jolt in the guts of the audience, providing an added tactility to the alarm of the mouse’s outburst.

Aimlessness in camera moves are reserved for the following scene as the cat wakes up and chases his so-called friend. Granted, the intent is there: camera movement indicates action, which proves helpful in contributing to any freneticism happening on screen. The same maneuver occurs in similar scenarios, such as 1939’s

Pied Piper Porky where a cat chases the designated mouse of

that cartoon. Regardless, the execution isn’t as polished nor motivated as it could be. The movement registers as the bare minimum: aimless motion to accentuate the animated fervor on screen.

In the end, it’s a moot point. The intent is communicated, just like the cat’s attempts to wrangle the mouse back into forced symbiosis. Casting the cat as the purveyor of Stockholm syndrome is an amusing choice; the aggression is consistent, but one would imagine that the mouse—if anyone—would be the one trying to keep things mutual in the face of danger.

Instead, he merely shrugs. This clearly hasn’t been his first attempt no escape. It likewise hasn’t been his first failure.

Thus, the short begins to climb to a close. A sleepy reprise of “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm”, an extended background pan of Dick Thomas’ tranquil backgrounds, the symbolism of the sun setting, and Bruce’s soft narration all bear a cozy finality. All is well on the farm—we have exhausted all that we need to see.

Almost.

The narrator’s huffy inquiry of “What in the

world can the attraction be?” isn’t directly answered, but does have the dignity of being met with a fresh layout of a pig watching the clock. A new camera angle and new background means new action—a breach in convention. Our answer lies in the fate of the minute hand, slowly chugging along to the top of the hour. Further anticipation is conveyed through the very slight movement in the pig’s eye as the hand keeps ticking; with every tick, a new eye is drawn, constructing the illusion of him watching the clock down to its every movement.

Remnants of Clampett’s Porky are visible in the faces of the pigs as they, too, embrace their anthropomorphic sentience. After having remained so stagnant for so long, the intensity in which they rocket off screen arrives as a genuinely startling yet effective juxtaposition.

Moreover, the speed at which they race into the pig pen is accurately accounted for. It doesn’t feel like it’s trying to be fast. It is fast. Camera speeds are fast, animation timing and spacing are fast. It is genuinely hurried, genuinely exciting; exciting from a technical front as well, seeing that Clampett has been able to get such a handle on speed. He has proven himself in this department time and time again (such as the climax of

Porky & Daffy, where Porky is hardly on screen as he rockets between the arena and his home), but there has been a bit of stagnation as of late regarding how to properly caricature the intensity and whiplash. This serves as a welcoming change of pace.

Logically, the camera settles down to focus on a particularly rotund pig eating her own dinner: the mama. The pigs are piglets, after all—mama is their dinner.

She knows this, too, for she immediately braces herself upon impact. The only thing more amusing than her children hurtling at her for an all-you-can-eat buffet is her readiness to accommodate; this is obviously a daily occurrence.

And it is, as the audience gets the unbridled truth directly from her mouth. Clampett does a fine job of maintaining any suspense he can; the brake squealing sound effects linger long after she and her piglets have been seen off-screen, again supporting the intensity of their bombardment. An added dose of cuteness is injected through a straggler who slips and slides a few beats behind—both to endear the audience, as well as introduce added visual interest through spaced, organic timing.

“Oh, dear…” Mama pig speaks in the manner of

ZaSu Pitts as she laments her role as a porcine feed bag: “Every day, it’s the same thing…”

Indeed it is. With our routine nearly topped off, the cartoon comes to a close, having succeeded in its mission of demonstrating life on the farm.

It’s nothing that hasn’t been said in the numerous times we’ve covered Tex Avery’s spot gag and travelogue shorts, but deserves reaffirmation regardless. Especially through the benefit of modern convenience, where any of these shorts can be summoned and consumed through a Google search, the spot gag shorts have an easy tendency to melt together in a fine mush. Obviously, the directors didn’t plan on consecutive viewings—most people would see these parody travelogues only once or twice a year in theaters tops. Repetitive structure and gags are more forgiven when understanding as such.

This isn’t to call the short repetitive. In fact, such is helpful in establishing the opposite: while it’s easy for the spot gag shorts to morph together and become indistinguishable from one other, Farm Frolics—while not exceedingly memorable—is a good, solid cartoon. It’s always refreshing to get a new point of view (that is, director) when regarding this format, and there are certainly touches in this short unique to Clampett’s own indulgences and line of thinking. Thus, there arrives a newfound novelty of viewing a familiar format adopted by someone else with differing ideas and approaches.

A big help to the success of the short is that Clampett seems to find a good handful of the gags to be genuinely funny. Not that Avery didn’t in his own cartoons, but there is a drive, focus and indulgence behind these gags that is not always present—especially regarding the past few years of Clampett’s filmography. Recycling some of these gags later on (such as the dog’s encounter with Dick Tracy, for one) indicates at least a certain level of attachment, but additional details that go the extra step—the horse grinning coyly at the camera following his scolding, the needlessly saccharine chorus of “Home Sweet Home” from the lovebirds, the baby ant’s butt exposed to audiences of thousands—indicate a devotion to the material and certain investment to it. Even in recycling older material, hardly any of the material feels like a throwaway.

It is certainly a step up from Goofy Groceries, which in itself is a fine cartoon. Groceries may have more spectacle to it (figuratively or literally, given that much of the short is presented by a showman), but this short has more focus, more comprehensiveness, and a stronger sense of conviction. It may not be flashy in the same ways Groceries is flashy, but it doesn’t need to be. The animation is overwhelmingly attractive, with only a few dwindling weak spots (such as the crudeness of the cat chasing the mouse, or occasional looseness on the pigs faces) and is an amusing indulgence of color. Likewise, lots of censor teasing that is always enjoyable when viewing Clampett’s work—especially if said censor teasing has only just been recovered to the public after having gone missing for decades.

Even if it isn’t one of Clampett’s most memorable shorts, it serves its purpose well and is a hopeful indicator of cartoons to come. And, given how the remainder of Clampett’s filmography did turn out, such proves to be a rightful premonition.

.gif)

I really enjoyed this review! It’s well written and I like that you take us step by step through the short. Being fairly familiar with old Daffy cartoons, I recognized the “Heeeenryyy” “coming mother” gag and I think I remember the “don’t you do that” one. As well as the scene of Daffy looking at the book. I was a bit unclear as to who the people you are talking about are and what roles they played in the making of the short. For example, Is Clampett the director? Anything else? What does that mean in this context? Who is Clampett? It’s possible I’m just not the target audience and most people would know all these people and what their roles entail already but that was the one thing I found myself wanting to know more about in the review. Thanks so much for this! Looking forward to reading more.

ReplyDeleteOr rather I see he’s the director but I don’t know much about him in this context or what a director for something like this is in charge of or not/how involved they are with every decision. Sorry if it’s a silly thing to bring up!

Delete