Release Date: June 7th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Norm McCabe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Daffy, Porky, Scream, Duckling)

(You may view the cartoon here!)While Daffy’s appearances have momentarily dwindled, with both 1940 and 1941 only boasting 2 cartoons each for the character, he has certainly made the most of what little time he’s had. You Ought to Be in Pictures was a watershed moment for the character, and the developments established and inflated in that cartoon have begun to be adopted by other directors.

In other words: Daffy has entered his teenage years.

Indeed, A Coy Decoy models itself after a duck who is comparatively more mature, more aware (if only marginally), and somewhat more versatile. Bob Clampett directs both of Daffy’s entries for 1941–the duck in A Coy Decoy is much more grown than the duck in his last Clampett outing: Porky’s Last Stand. Conversely, his next appearance—The Henpecked Duck—demonstrates an even more mature, even more versatile, and even more startlingly perceptive duck that makes this Daffy seem like child’s play.

It’s not to imply that Daffy’s growth was stalled before the inception of Pictures. Even as early as The Daffy Doc, developments surrounding his perception, his consciousness, and the general manner in which he conducts himself are clear. The time between 1938 and 1939 offered him a lot of room to experiment, to grow, to establish little character traits that would later be inflated and embraced to easier recognition by both the directors and the public. Like all of these characters, Daffy is an ever evolving experiment—Pictures just happened to be the activating ingredient to jumpstart his growth. Thus, A Coy Decoy offers the first glimpse of the after effects, the short that begs the question: “Where do we take him from here?”

Still, Daffy is not completely lucid, as he has to live up to his namesake somehow. The short is, surprisingly, another effort in the books come to life genre, and the first of its kind to plunge studio mascots into the role. While branded as a Porky and Daffy team up, the short is much more a Daffy cartoon than anything, with Porky only there to appease any contractual obligations. We follow Daffy’s run-in with a particularly nefarious wolf, who lures him into his clutches by means of a duck decoy.

Clampett’s experience on this short would largely be informative of the success of Book Revue in 1946, which is constructed in the same mold. Even the opening of this cartoon—the sleepy façade of the book store scored to an almost somber accompaniment of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 14–would be reused directly in the latter, directly recycling the photograph of the book shop.

Likewise, both follow a long pan within the book shop, exploring its contents before eventually settling on a point of interest. Clampett’s pacing was much more deft in 1946 than it was in 1941, resulting in the pan being about ten seconds longer here. That isn’t a complaint; both of these shorts, while very similar, boast different needs. Book Revue is a frenzy of a cartoon that doesn’t chew on the scenery as much as Decoy’s opening, which has its own purpose of establishing the context and lulling the viewer into a false sense of security.

Indeed, the introduction maintains its stolidity for the sake of establishing a stronger antithesis when the animation eventually does come into play. Like the exterior of the store, the books are photographed—not painted—with real covers and real titles that remain recognizable to viewers even today.

The descent into cartoon antics is gradual. Intriguingly, they are first initiated not through the appearance of an animated character, but through the cover of a book itself—the cover to Uncle Tom’s Cabin is clearly the background work of Dick Thomas, the house proudly boasting a F.H.A. sign that is derivative of a synonymous gag just used in Farm Frolics. It’s subtle, but such a little jab encourages an indiscriminate crack to break the ice.

A crack that is finalized upon focus of The Westerner; a camera truck-in and dissolve clarifies Porky’s place on the front cover, quaintly nestled by a campfire that crackles to life when under the eye of the public. Courtesy of some attractive animation by John Carey, Porky is given the go ahead to sing an equally attractive rendition of “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride”.

Charming and earnest, the song number doesn’t feel nearly as ham-fisted as some songs have tendency to feel in these cartoons—Clampett shorts especially. “___ come to life” cartoons have always been structured around melody and music, and while the spot gag format isn’t as rife in this short as it is others (thusly making the song feel somewhat disconnected from the overall story), it still serves as an entertaining and focused vignette. It feels more than a haphazard means to fill time.

.gif)

Porky/Mel Blanc’s vocals are in tip top shape—a surprise to nobody, but praise that deserves to be reiterated. Even in spite of his stutter, occasionally getting strung up on a word or two, the song maintains its melody and rhythm and exercises patience with Porky. There are plenty of instances where his struggle to stay on bear can be amusing and endearing, especially with Carl Stalling repeatedly vamping the music in the background, but that isn’t a purpose that requires serving at this moment. Porky’s just there to set the tone and look cute, be endearing; he accomplishes all of the above with ease. Brief as his solo may be, it’s one of my personal favorite snatches of a song in a Warner cartoon to date. The atmosphere is infectiously charming.

Similar to the photorealistic books offering an antithesis to the soft, animated qualities of Porky and company, Porky’s song (and the attitudes it adopts) stands as the perfect juxtaposition to Daffy’s own chorus. Delegated to the lowly status of the eponymous Ugly Duckling—“a story for kiddies” added for additional ribbing, essentially pigeon holing him into nothing but kiddie fodder—he observes with a vacant patience. No issue is taken with the insults directed to his home; who knows if he’s even entirely aware of their implications. He is Daffy Duck, after all, and Daffy is a crazy, blithering fool. Right?

Yes and no. He now possesses enough agency to know when to delve into a chorus of his own—perhaps if this was a short produced in 1938, Porky would have been interrupted with a series of shrieks and whoops and other hysterical acrobatics. The audience gets the sense that he’s still a little out of it, but segueing immediately into a chorus of “I Can’t Get Along, Little Dogie” is indicative of an awareness of some kind.

Themes from You Ought to Be in Pictures already adapt themselves to the needs of this cartoon by Daffy’s drive to break convention. Porky stays within the confines of his book, contented with his lifestyle as a singing cowboy who performs on the off chance that wandering eyes are peeking. Sitting down by a lapping fire indicates a commitment—he isn’t about to take off in a rush any time soon, and he certainly isn’t going to leave the sanctity of his book cover.

Jumping out of the bounds of the book is almost the first act that Daffy even does. Too stifling of an environment for someone like him, where being chained to one single role, thought, or spot is instant means of torture. Is jumping out of books a taboo in the world of “come to life” cartoons? Daffy shows a clear disregard regardless—maybe he doesn’t know such a taboo exists. Maybe he doesn’t know to pause and question the plausibility of a taboo. Or, more believably: maybe he just doesn’t care.

Even his song choice could be considered radical. “Ride, Tenderfoot Ride” was still relatively contemporary for 1941, released in July of 1938, but “I Can’t Get Along, Little Dogie” was even more so. It was featured as a song in the Vitaphone short Cliff Edwards and His Buckaroos; there are conflicting accounts as to whether the short was released in 1940 or 1941, but is certainly much more fresh in comparison to Porky’s choice of song.

There’s also the fact that Daffy’s performance doesn’t entirely constitute singing—whooping and hooting and even some frenzied horse impressions are likewise a staple. To the credit of Clampett, these outbursts are approached calculatingly. It genuinely feels as though Daffy can’t repress himself, can’t put on a lucid façade for much longer. The temptation to whinny like a horse and to whoop inanely is too enticing. He’s managed to stay quiet and wait for his cue, and has been able to belt out a few bars; this self indulgence is as much a reward as it is a necessity. He may have matured since the last time Clampett dealt his hand in Porky’s Last Stand, but his on and off fragmented tendencies remain for the time being. Daffy isn’t Daffy without his predictable unpredictability.

Talks of defying convention transcend to a complete disregard for proper physics. Upon the verse of “Yer wearin’ a ten gallon Stetson,” Daffy summons that very hat with a mere wave of his arms. No questions are begged by the direction, which encourages the audience to remain neutral—it’s just something that happens. A follower of the philosophy that Clampett himself instated in Porky & Daffy, and in Daffy’s own words: “I’m so crazy, I don’t know this is impossible.”

Backtracking to focus on some details, there stems a brief bout of difficulty with the double exposed camera effects (accounting for Daffy’s shadow). It’s mainly noticeable when he first jumps out of the book, preceding his crazed horse impression—the images seem to blend and bleed together, leaving a semi-transparent after image as the camera lens momentarily dips out of focus. Likewise, a jump cut to a marginally more intimate angle of the same layout seems arbitrary, fragmenting the pace of the momentum… but isn’t a noticeable enough of a maneuver to truly harp over.

On a more intriguing note, ___ come to life cartoons are often rife with opportunity for inside jokes and references. A Coy Decoy proves to be no exception to such indulgence. Albeit difficult to see, sharp eyes will catch that one of the books in the background touts the label “Kirsanoff”—such is an allusion to animator Anatolle “Tolly” Kirsanoff, who would have been an assistant animator at this point in time. He would rise up the ranks to a full-time animator, working under the direction of Frank Tashlin and Bob McKimson; he evidently moved to the Walter Lantz studio by October of 1941, indicating a brief return to Warners in the mid-40s before pursuing other ventures elsewhere. He was one of a handful of Warner alumni to have worked at Disney, getting his start in 1937.

Another jump cut occurs when Daffy runs along with his cowboy hat; the perspective of the character himself remains the same, whereas the background changes under him to accommodate for the visual that follows. A visual that both communicates and doesn’t at the same time—the intended effect is for Daffy to weave in and out of the foreground in perspective, accentuating the deftness of his leaps as he jumps to and fro across the screen. Gentle, airbrushed backgrounds dominate the new camera pan, communicating dimension and depth through a lack of focus.

Indeed, the intent is communicated, and logically at that. However, the end result seems more akin to Daffy rapidly shrinking and growing on screen rather than moving in a tangible perspective. It’s a rare case where additional, seemingly arbitrary camera movement could be helpful, zooming in and out each time Daffy lept away from the foreground to convey the hypnotic, rhythmic jumping struggling to be finalized. That, or lower the horizon line of the background and position the books even further away.

His song continues to be fragmented by outbursts and tangents—a bonus for the entertainment of the viewers, as Daffy almost slipping into the timbre of Woody Woodpecker is certainly nothing short of entertainment. An awareness is established regarding his role as a performer. He’s lucid enough to know he has the spotlight, that he’s in a “come to life cartoon” which often demands singing and dancing; his showboating and spastic betrayals of song, however, ground him back to his own reality. Or, in this case, lack thereof.

Regrettably, the on-and-off vaudevillian sensibilities result in a particularly heinous racial gag. Getting more and more wound up with the song, Daffy’s lucidity continues to lesson as his impulses beg to take over. Aimless song-talking in the vein of a mush mouthed Al Jolson soon transforms into a crescendo of whoops and hollers that are exceedingly reminiscent of the “old” duck in Clampett’s cartoons. This in itself is fine: the predictability of Black Beauty being a mammy-type caricature bucking Daffy around like a horse is not.

Bad faith at best and utterly dehumanizing at worst, the gag isn’t even unique to Clampett. It serves as a takeoff of the same gag in the 1939 MGM film, The Bookworm, which was directed by Friz Freleng amidst his tenure there. It even features the vocal talents of one Mel Blanc.

The scene can be best surmised by the cartoon itself: a brief tangent of a bewildered Porky observing within the quiet sanctity of his book speaks its own volumes as he merely looks on with wide eyes. Granted, his reaction is directed towards Daffy’s complete lack of inhibition and the insane outburst that he had been making an attempt to repress so dutifully for the past few minutes rather than a concession of the gag being disgusting, but the point remains.

One may also take note that his campfire has dwindled to mere smolderings of smoke; a clever indicator that Porky’s time of relevance is no longer, seeing as the cartoon adopts unobstructed focus onto Daffy (and Daffy adjacent matters) from here on out. It likewise could be construed as Daffy stealing his thunder—or, in this case. flame—as he is the bright blaze of energy and fire… even if only in a metaphorical sense.

Mercifully, the mammy bucking Daffy into the cover of The Lake is the last we see of her, as it’s the book that dominates much of the short’s screen time.

While anyone else would take issue with suddenly being doused into the water, Daffy rolls with the punches—outside of appearing slightly disoriented or even dejected, coming down from the high of his mania, he indulges in finishing the rest of his song which adopts a notably leisurely tone. Reeds in the foreground create a clear and clever frame within the composition, gently guiding the audience’s eye to Daffy and Daffy only.

Likewise, physics on the water are handled well—especially with the beat of Daffy slapping a sopping wet Stetson onto his head, the weight of being so waterlogged transcends the screen with its tactility. Droplets may not be portrayed the most realistically, but believability isn’t a priority. Effect and caricature of the weight is. Droplets are tapered enough and dissipate to read convincingly, but are approached with a graphic, geometric blobbiness to them that encourages a heavier sense of weight that is married to the physics of the hat and Daffy’s body quite well.

“The water looks wet” may seem like an absurdly simple compliment—and it is—but deserves acknowledgement for the success of the coming gag. Daffy’s hat suddenly shrinking into practically nothing hinges on his waterlogging; if the water wasn’t approached with enough obtuseness or believability in its physics, the hat shrinking would read as a random non-sequitur over a logical consequence alluded for the past 15 seconds or so.

Outside of a gag made in staggeringly poor taste, both Daffy and Porky’s songs prove to be exceedingly entertaining and endearing. On the surface, they’re an energetic way to occupy a minute and a half. The songs are catchy, Blanc’s vocals are infectious, Stalling’s arrangements inventive and lush. They succeed at their job of fulfilling the song-and-dance quota established by most “come to life” cartoons without feeling entirely like an obligation and nothing more.

Scavenging deeper, it’s a fascinating reflection of parallels between Porky and Daffy. Porky the mild-mannered conservative who is contented with his assigned role and doesn’t think to question it. He does as he is asked, and goes as far as to seem shocked at such a breach of convention as exercised by Daffy. Daffy, who shows no concern for rules or structure and does as he pleases, falling victim to his impulses and inhibitions. Directly placing both segments back to back enables the audience to compare, contrast, and assess the antitheses clearly. It is indeed a very effective parallel that is more than just “Daffy is more interesting, so he gets a longer spotlight”.

With such business matters attended to, the cartoon delves into its meat and potatoes through the introduction of

The Wolf of Wall Street. One would be correct to assume that an actual wolf resides in its contents—quite literally, too. Whereas most characters in “come to life” cartoons are directly introduced on the front cover or label of whichever object they’re occupying, the wolf peers furtively within the book’s pages. Much like Daffy jumping out of the bounds of the book, this, too is a breach in decorum, which sheds light onto potential nefarious activity. If this wolf doesn’t reside proudly on the cover like the rest of the model book denizens, then surely he is a ne'er-do-well just itching for trouble. Pages of the book moreover offer further protection and hiding to obscure any wrongdoings or evil deeds; sitting on the cover is too bold, too risky.

The wolf appears more like a coyote or even a dog instead of a bonafide wolf, and has a tendency to vary in design. While stylistic inconsistencies aren’t entirely intentional, a dissonance spawned by the comparative believability of his design is; the closer he looks to a feral, wild animal, the more antagonistic he seems. Thus, sympathies and subsequent interest are projected onto Daffy instead, whose personality, looks, and behaviors all read as much more human—even in spite of the caricature and gravity regarding some of said behaviors.

Adoption of Freleng’s sensibilities isn’t only delegated to the handling of Daffy’s being. Influence of his musical timing is particularly clear in the wolf’s furtive attempts to hide—the head tilts, the arched tiptoes, and sudden bursts of speed that ensues as he takes cover are all highly reminiscent of Freleng’s own spin that would soon become one of his trademarks. Louis Bromfield’s 1924 novel

The Green Bay Tree offers adequate shelter to hide behind in bridging the sequence together.

Daffy filing his nails and humming idly is yet another behavior that probably wouldn’t have implemented without the developments of

Pictures—or, at the very least, not so soon. Not that

Pictures was the first short to give Daffy an ego; Chuck Jones’ Daffy maintains a recognizable, trademark conceit from day one, even in

Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur, and Clampett’s own Daffy certainly harbored an entitlement in shorts such as

Scalp Trouble or

The Daffy Doc.

Regardless, there is a certain human haughtiness to the simple act of filing one’s nails. Outside of the amusing implications that Daffy even has nails to file, it conveys a polite vanity—filing nails indicates an awareness that nails need to be filed, which segues into a regard for one’s physical appearance and how it is presented to others. Such trivialities don’t seem like they would have ever been something to plague Clampett’s Daffy, much less cross his mind. It’s an act of awareness, which, again, is ever changing and continually observed.

Even (and especially) if said awareness is oxymoronic in a sense, as Daffy seems completely oblivious to any presence of the wolf or the toy duck that he utilizes to lure Daffy in. The difference in draftsmanship and style between the shot of the wolf ogling at Daffy and his retrieval of the decoy is one of the most apparent; his construction is much more solid and tangible, his fur almost disarmingly sleek.

Realism in his human-adjacent paws is capitalized upon through a close-up of the wolf winding up the toy duck; such solidity, in both structure and perspective, provides a refreshing change of visual pace.

The silence that dominates when the wolf places the lure in the water is genuinely suspenseful. Treg Brown’s squeaking effects substituting the sound of Daffy filing his nails—an endearingly juvenile sound choice that seems to poke just the slightest bit at his behaviors, as if Clampett himself was aware of how asinine of a gesture this is from a little duck in a pond—are the only sounds that dominate, delegating focus onto Daffy’s presence and reminding the audience that danger lurks around the corner. Much more effective of a maneuver than occupying the space with a laden music sting; that information guides the audience to feel apprehensive, to inform them that things are tense. A lack of music is a lack of a cue, which gives the audience the agency to derive their own feelings from the matter in comparative independence.

Regardless, that gap is soon replaced through a tinkling, playful motif of “

In An Old Dutch Garden”—a song choice often employed by Stalling and company when surrounding toys. There is also, of course, Daffy’s fragmented humming of “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride” that mingles overtop the jingle, creating a blend of aimless noise that is intended to be a distraction—such expounds his obliviousness regarding the decoy, enunciating how long it takes for him to fully register its presence. Having his eyes trail the toy’s rounds without actually interpreting the intentions is an attentive acting decision that informs the audience of his oncoming reaction—he will take note—but to recognize it right away would seem too perfect, too mechanical, too orchestrated. He’s still a little out of it. Still in his own world.

However, when he does register the decoy’s presence, he registers it with vigor. A spiral head take in the vain of Izzy Ellis quickly segues into a close-up of Clampettian indulgence and perhaps his most memorable exercise of the gag: Daffy’s eyes traveling the rotations of the toy, which includes rolling into the back of his head.

Such a visual extends a bit longer than what is truly necessary. Not to a heinous degree—the intrigue and attention in the visual certainly makes it worth the audience’s time. A shadow of the duck decoy traveling across Daffy’s beak instills a permanence, indicating that Daffy’s eyes aren’t traveling just for the sake of traveling. It’s a cohesive and incredibly amusing gag that is certainly fitting for a character like Daffy, whose bravado allows such grandiose and exaggerated optics to thrive comfortably in his association. Its only flaw seems to be that it lasts one rotation too many, but even that is subjective.

His entrancement is so deep that it inspires two separate cutaways to an eye take of some sort; this inadvertently stalls the momentum of the sequence, chopping it up into new bits of information every few seconds, but the general idea is communicated with ease: the wolf has got himself a sucker.

Execution of the decoy swimming away towards the general direction of the wolf is particularly nice through subtle details. Namely, the giant cluster of reeds that inadvertently splits the screen into two: the space occupied by the decoy, and the space occupied by Daffy. Even though they’re only a few feet from each other, any physical barriers purely an illusion of perspective, such a touch makes the decoy seem out of reach, separated. A barrier is installed that is begged to be broken.

Perspective and construction of the decoy in particular continues to maintain its solidity, as ensured through a close-up of the decoy beckoning Daffy closer. Throughout all the scenes that it’s relevant, Clampett handles the decoy with a playful sentience that is proud in its own breach of convention. Being a toy, there is no possible reason how or why its stiff, plastic tail feathers should morph into a fleshy, solid hand that draws Daffy in with the wave of a finger. That’s because there doesn’t need to be a reason—to question and to explain is to concede. Clampett’s approach of no questions asked regarding his physics and sensibilities is just one of many reasons as to why his shorts are so alluring: playfulness always comes first.

Likewise, the toy duck’s eyes travel when necessary to indicate further sentience and pathos. While it should be staring straight ahead, the eyes are positioned in its corners to seem as though they’re looking at Daffy. Such not only directs further focus to Daffy’s presence off screen, making the flow between scenes more comprehensive, but also justifies Daffy’s fixation with the duck. The effect wouldn’t be the same if it maintained that same, vacant straight ahead stare—it has the potential to certainly be funny, but isn’t the type of humor that Clampett seeks to prioritize for the time being.

A third and final eye take is the charm. Daffy’s commitment to pursuing the decoy was never called into question, but is certainly solidified as he turns is attention to the audience. Rather than entertaining them with a wolf whistle or any sort of candid comment, his feelings on the matter are best conveyed through ‘40s slang that soon became number 10 on Billbord’s Leading Music Box Records of 1941: “Well!

Beat me daddy, eight to the bar!”

Such intimacy regarding the audience certainly isn’t new for Daffy, lest one forget his raving spiel in

The Daffy Doc, bragging about his painting skills in

Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur, or his contemptuous grimace towards the camera at the end of

You Ought to Be in Pictures. However, it should be noted that this is one of the most conscious acknowledgments to stem from him yet, if even only in a Clampett cartoon. The raving seen in

Doc was more of a candid catharsis than an actual message to the audience—they just happened to be catching him at the right moment.

Dinosaur’s witty quip is certainly more motivated, but in a similar vein that the audience is in a spectator role who he can spare a line to before attending to other ordeals. The end of that short is a little more in line with the tone of his acknowledgment here, but Clampett certainly didn’t adopt the attitudes of Jones’ duck with the same haste he evidently did Freleng’s.

For Clampett’s duck, this is a noteworthy occasion. That character-audience relationship has always been an integral keystone to Daffy’s foundation, and would remain so all through his career. Clampett in particular would play a big role in emphasizing and embracing such a dynamic—

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is entirely reliant on it. So to mark such an unmistakably conscious acknowledgement, completely menial and arbitrary as it may seem to comment upon, is not without waste.

The Henpecked Duck would really be the cartoon that examines this tactic from multiple angles, but the growing sentience of Clampett’s duck continues its progress.

There is also the development of Daffy’s libido—raging, as the next minute of the cartoon so details. Frank Tashlin in particular would garner a lot of mileage out of it, as every single one of his shorts that involves Daffy has him lusting over someone or something. It’s a trait that, as silly as it may sound, makes sense for the character; it’s a way to enunciate his lack of inhibition, his impulsivity, his brashness. Indulgence makes up the very fiber of Daffy’s being. Adrenaline dominates his decision making (or lack thereof). His zest for life extends to anything deemed desirable or attractive, especially if it’s at his benefit. That could be something as simple as desiring to heckle someone or desiring to make love to a decoy, as is the latter case.

Thus, a grand entrance is in order for an even more grandiose spectacle of lust. He twists his body into a running start. Reeds and plants are left sailing violently in his wake. It takes multiple seconds for his body to come to a complete stop; the combined intensity is very powerful and effective—even moreso when remembering that this is all over a toy duck, who is purposefully angled in that specific shot to appear as plastic, lifeless, and apathetic as possible.

Daffy’s futile attempts to woo the decoy is easily the short’s highlight—Mel Blanc’s deliveries are laugh out loud funny, rising in a crescendo from antithetically soft spoken to shameless, almost hysterical moans. Just as the sequence is reliant on vocal performance, it is just as dependent on solid, informative animation that can carry the verbal grandeur convincingly. Thankfully, that is absolutely the case.

A part of such amusement stems from a historical viewpoint—the intensity and sheer caricature of Daffy’s affections are certifiably daffy, keeping him grounded to his roots, but this is nothing like we’ve seen him in before. Recurring attitudes are all there: the impulsivity, the recklessness, the obliviousness, the drive, but the audience is almost surprised Daffy even cares about such romantic pursuits (though “flings” may be the more suited term.)

Such is carried through his breathless, awestruck delivery of “Sweetheart…

where have you been all my life?” It implies a history, a prolonged search for the perfect partner when clearly no such idea was ever on his mind until he first laid eyes on the decoy. If he were truly that hard pressed to seek out a flame, he would have long done it by now. Especially given that she resided on a book cover in the same bookstore as him, and he easily could have spotted her at any time. While his declaration is a sincere exclamation, the audience is endeared through the striking artifice of his statements.

Again, it’s that oxymoronic awareness and lack of awareness that makes him so charming. He’s completely oblivious to the fact that he is absolutely not the romantic type whatsoever, and no amount of moans, groans, or hilariously disingenuous French accents (eventually just devolving to communicating in song titles, as though that’s the only way he can think of expressing his affection—“All This and Heaven Too”, for example) will change that. Granted, that doesn’t matter; it’s his conviction to the role that is so intoxicating and so humorous, clinging to his belief that he really is a velvet voiced Casanova; in fact, it’s almost disarming.

A lack of awareness is more poignantly acknowledged regarding his obliviousness to who—or what—he is attempting to seduce. Amidst his performance, a clawed hand slowly eases the duck decoy out of reach…

…which proves no problem for Daffy, as he unknowingly seduces the muzzle of a snarling, hungry, and aggravated wolf with an even stronger lustful ferocity.

Clampett and the animators cheat the wolf’s snout to fit the needs of the scene. While the design calls for the nose to be embedded into its muzzle, Daffy turning it over in its arms prompts an opportunity for the nose to become bulbous; such better supports the illusion of Daffy actually cradling someone, with the nose substituting as a head. A very clever and very subtle cheat that is delivered naturally, not calling too much attention to itself and not afraid to break “the rules” to better serve the needs of the sequence.

Moreover, this allows for more success regarding Clampett’s climaxing innuendos. If the nose is the head of the “decoy”, then the muzzle of the wolf framing its mouth is its nether reasons. A close-up purposefully illuminates Daffy getting grabby, with the audience able to see the muscles of his fingers bulging as he squeezes. Disturbing, and incredibly effectively so; the animation is remarkably solid, whether it be the weight and believability of the actual motion or the staggering solidity of the draftsmanship and construction. Such solidity enunciates Daffy’s creepy advances to the desired effect.

Especially when he feels the wolf’s tooth, who finally opts to bare its fangs after surprising patience. Given how proudly sophomoric Clampett’s sense of humor could be—something made more apparent in his heyday, but is noticeable all around—it’s logical to deduce that Daffy isn’t taking the tooth for a tooth. Not if it’s so close to the decoy’s general rear area. The sudden halt and slow burn of him feeling up the tooth is handled with incredible grace in the drawings. Likewise, such a deliberate slowing of movements arouses a genuine laugh from the viewer, as the audience can feel Daffy struggling to make sense of it in real time.

All of the above are confirmed through the finality of a wide-shot, Daffy ogling at the audience with wide eyes as he aimlessly flicks the tooth to confirm its placement. A complete lack of musical orchestrations enables the gravity to smother the sequence, introducing further sympathy towards Daffy, who’s clearly expending all of his energy attempting to decipher his mistake. Empty, vibrating “TONG!” sound effects confirm a further permanence of the tooth—bad news for particularly appetizing, uninhibited ducks.

Urgency in which Daffy thrusts the wolf’s snout to his face is beautiful. Steaks of dry brushing completely douse the scene in ink—while excessive dry brush can have a tendency to dilute animation and even seem to slow it down if the animated drawings themselves retain an even, methodical spacing, the effect works to Daffy’s benefit here. It’s sudden, it’s erratic, it’s excessive. Just like Daffy. Maneuvering the snout to get it at eye level prompts Daffy to twist and contort and conform his body, which in itself is proudly extraneous; elongated streaks of black allow such frenzied motion to hang in the air and thusly linger longer in the minds of the audience.

Reflecting Daffy’s eyes off of the black sheen of the wolf’s nose is a great way to build further pathos. For Daffy, it’s a beat of unadulterated humanity—eyes are the window of the soul and all that jazz, and to have them reflected back at you in wide, calculating terror induced the audience to feel sympathetic. Moreover, the shininess of the wolf’s nose makes him feel more threatening, more in shape, spry and ready for a kill. All of the above are maintained as the nose stays firm in Daffy’s grip despite the wolf preparing to get up.

The pile of melting duck flesh that ensues would be another inadvertent watershed moment regarding Daffy’s development; it mainly serves the purpose to exaggerate his emotions, give the humility and terror a physical manifestation. It’s a funny visual that informs the audience of what Daffy is feeling. However—with Clampett’s cartoons especially—this would become a defining trait as the years went on, with Daffy’s physical state freely able to transform given his emotions.

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, for example, boasts a gag in a very similar vein where Daffy literally shrinks into himself with resigned meekness. Not just comforting his body into a ball, but physically getting smaller and deeper into his body.

This puddle of duck flesh is a vast development over his reactions when in a similar situation of peril in

Porky’s Last Stand—his giant, sly smile is certainly hilarious and another caricature of his emotional state, but still native to the construction of his body. It may be easier to pin this as a comparatively more aware reaction, since he merely blinks (noted through Carl Stalling’s string plucks in the background) rather than sweating, grinning, woohoo-ing and other theatrics. Don’t be fooled. Just because the reaction isn’t loud audibly doesn’t mean it’s not loud artistically.

With that, we literally jump into the next scene through the courtesy of a sudden jump cut. Jarring as the suddenness of the cut may be, part of that rapid disconnect between scenes seems intentional. Its abrasiveness connotes anxiety, rapidity—fitting for the atmosphere and helpful in offering more sympathy to Daffy’s plight. If only for a second, the audience is momentarily put on edge and, thusly, placed in Daffy’s shoes. If that sudden cut made us feel uneasy, imagine how it must feel to find that your girlfriend-to-be is actually a duck eating monster who doesn’t seem ready to listen to reason.

Likewise, there’s the comparatively more uninteresting justification for the cut that it saves the animators the trouble of having to depict Daffy materialize into his regular self. A clever cheat that proves successful in multiple ways, even if it may seem like an error from the outside.

John Carey continues to assert himself as the MVP of the Clampett unit, excelling in solidity and acting regardless of character. His eye for detail, convincingness in structure, intimacy in acting, and incredibly appealing draftsmanship are always appreciated, no matter the circumstances, but are especially instrumental in selling Daffy’s urgency and the directorial pathos as he desperately attempts to bargain with his captor.

“Bargain” being the key word here: this, too, is an important development. Porky’s Last Stand was radical for demonstrating a Daffy who was finally aware of the consequences of his actions. Maybe not completely understanding of them, but aware that he screwed up and is seconds away from being mowed over by a raging bull. He made an attempt at artificial niceties, such as patting the bull’s head and exercising that giant, disingenuous grin, but eventually resorted to running, insulting, and cowering behind an oblivious Porky who proved to be just as helpful (that being, not very) as him.

Now, Daffy takes the time to reason with the wolf. His reasons as to why he’d make an inadequate meal are approached with a mischief and exaggeration familiar to his character (“Look—even my tongue’s coated!” prompts him to thrust out said tongue, which is neatly dressed in a suit jacket), but displaying enough agency to try and talk his way out of the predicament—futile as it may be—is an impressive development. With all of the absurdity of his excuses and their coinciding visuals, a novel lucidity upholds their foundation.

Speaking of

Last Stand, similar artistic philosophies of that short are adopted in the wide shot of Daffy begging not to be eaten. In the former, a particularly menacing customer that is tangentially responsible for Daffy’s woes is depicted entirely through silhouette. Though he is merely but a shadow on the wall, Daffy (also animated by John Carey in that instance) leans away and interacts with the absence of light as though it were a real, living being on the wall.

Here, he behaves the same with the shadow of the menacing wolf projected against the book cover. Carey has the wolf moving on an idle cycle, slowly easing into frame as his mouth opens and closes with each heaving breath. Such idle animation makes the beast seem more threatening, as it confirms he’s living, breathing being ready to strike. Anticipation is stronger rather than what would be present if he were just a static projection of a shadow.

Ben Hardaway of all people serves as an inspiration for some of Daffy’s pleas; his despairing “Look, I-I’m just skin an’ bones!” prompts him to mummify himself in real time. A synonymous gag was first seen in

Hare-um Scare-um—needless to say, the exaggeration and circumstances surrounding Daffy’s demonstration is twice as striking and grotesque.

Grotesque is his exact intent; turn off the wolf with talks of dandruff, B.O, deviated septums… his grandstanding is amusingly fierce, as most—if not all—of his self “critiques” are reflected visually. Dishpan hands elicits excessively pruned hands, whereas a seemingly interminable supply of dandruff is pried loose from his scalp with ease. The hysteria he undergoes to prove himself is, again, certifiably daffy, but there’s a persistent levelheaded reasoning behind his begging and groveling and excuses. Can you really blame him?

“Why, even the army don’t want me!” Daffy’s now reduced to sobs, his freneticism climaxing into the far more recognizable vessel of shouts. Not that he’s exactly been calm throughout this short, but, as has been harped on so repeatedly, his prolonged lucidity is truly a fascinating breakthrough. One wonders how long until he can’t give into his temptations any longer—permanently.

In any case, his rejected draft card (which tells a story of its own, especially when remembering Clampett would later center an entire cartoon Daffy’s frenzied attempts to dodge the draft board) receives a second rejection: this time from the wolf, who sinks his fangs into the paper. Again, the gift of lucidity is enough to tell Daffy that he’s next.

Thus, more native hysterics resume as Daffy assumes his trademark Stan Laurel hop—always the starting pistol in the histrionics to come. However, rather than in a case such as

Last Stand where said hopping seemed to be a gleeful catharsis and a return to unbridled insanity, his hopping hoo hoo-ing is almost like an unconscious gut instinct. He isn’t gleeful or excited at the prospect of a chase. Instead, he’s exhausted all options of how to react other than to run—this prerequisite whooping just seems to be what he knows best in that instinct. A futile means of self defense.

A chase offers Clampett and writer Tubby Millar more opportunity to lean heavier into their book theming. More instances for further wordplay and inside jokes—one book that Daffy and the wolf breeze by in a pan notes not only background artist Dick Thomas, but story and layout man Michael Sasanoff. His name would become more frequently associated with Clampett following his adoption of Tex Avery’s unit later that year; he had previous animation experience working at Fleischer Studios in 1939, before eventually moving over to the Schlesinger studio. A career in television awaited him in the late ‘40s after he left Warners, creating Telefilm’s Sunny the Rooster in 1948.

Books prove to be equally helpful means of escape as they are obstacles. Francis Yeats-Brown’s 1933 novel

Escape offers the exact relief that Daffy has been looking for, a shining sun and a long winding path that promises to guide one far away is depicted as luxurious, relinquishing, and desirable through the above visual clues.

If only a giant, menacing wolf weren’t in the way.

Daffy’s frenzied whooping is more akin to the duck of yore, both from the sheer volume/frequency of said whoops and the cruder, spastic animation. The more he is threatened, the more primitive of a duck he becomes, reverting closer and closer to his roots. Not to imply that any levelheadedness he displayed earlier on was a façade—the evolution he’s consistently undergoing is tangible—but one would be truly hard pressed to take the hysteria out of a duck who has it right in his name.

Meanwhile, Clampett leans into a different brand of daffiness following the chase. In seemingly random increments, Daffy skids to a stop, now brazen enough to get beak-to-muzzle with a visually petrified wolf. His snarling “Say—are you followin’ me?” would be reused in multiple Warner cartoons of the ‘40s, whether it be Clampett’s own (

The Hep Cat) or in further association with Daffy (

Duck Soup to Nuts.) Such a sudden outburst of stolidity and brazenness may seem like yet another sudden burst of cognizance, a cool down from the highs of manic whooping and shrieking and the acrobatics therein.

If anything, the gesture is one out of even more insanity. Anyone in their right mind would certainly not stop a chase just to have an aimless word with their pursuer before taking off again—that extra few seconds could have been well spent running away.

Any levelheaded individual certainly wouldn’t do it twice, let alone once. The reprise is mainly another means for Clampett to indulge in his love of pop culture references and have a sure fire way to get a laugh from the audience, but one could loosely argue that Daffy’s recital of The Great Gildersleeve’s catchphrase on

Fibber McGee and Molly—“You’re a

haaaaaaar-r-r-r-r-r-r-d man, McGee!”—is the start of a years long obsession with pop culture.

Indeed, an endearingly recurring trait of Daffy’s throughout the ‘40s is making allusions to certain pop culture iconoclasts. While much of it is indeed just the writers and directors having fun, marking and embracing their own awareness of pop culture and hoping to amuse the audience through well known references, Daffy’s allusions are multiple and a natural fit to the character. Perhaps all of this stems from the hindsight bias of knowing The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, an entire short about Daffy’s unbridled fanaticism over Dick Tracy, lies ahead. Still, his frequent references to Dick Tracy characters in multiple shorts, or a shout-out to Major Bowes’ radio show, likening himself to Popeye in a moment of weakness, or just a mere recital of a catchphrase are enough to feel like a fitting personality trait. Daffy is a creature of indulgence. Of course he would indulge in the same cultural joys as us. They’re exciting, they’re engaging, they’re new. It’s just yet another way he’s able to bridge a strong relationship with the audience, bonding over likeminded interests.

Nevertheless, the chase goes on. It is here where the books are utilized for their physical stature (rather than a means of demonstrating animated or stagnant gags within the confines of the cover)—for example, Daffy gets tripped up on a blank memo book, whose pages partially slow down his momentum. Most book cartoons before this maintain their antics solely to the covers and the characters within, with any tangible action happening both inside or outside the cover. Actually using the books like real books (or obstacles, in this case, whether it be the memo pages or a bridge of teeth on the cover of Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Ray) grounds the audience back to reality in a mischievous, warped way. There’s nothing realistic about getting caught on a ton of blank pages in a life or death pursuit, but it gives the environments a tangibility in some way.

Insignificant but endearing acting note, backtracking a bit: Daffy plugs his “nose” as he jumps off of the shelf, as though he’s bracing to dive into a pool of water and not navigate a bunch of obstacles. The action gets lost in the deft pacing and scale of the shot, but is a great piece of character that—if only on a subconscious level—reminds the audience of the playfulness inherent to Daffy’s personality.

As both dash through the bookstore, the camera gradually trucks closer into the action. It’s an incredibly slight gesture that doesn’t immediately register—a subconscious encouragement of additional dynamism and motion, instilling a further tactility to the action that aids in intriguing the audience. Likewise, it’s just different. Other similar camera pans did not have zooms. This one does. A quick, easy way to break up any monotony that can often be as much of a threat in chase sequences as the pursuer themselves.

Any whispers of impending monotony through a long winded chase are quickly silenced through Daffy’s accidental encounter with the book

Hurricane. Slamming into it face first, some surprising forward thinking results in him scaling to the top and opening its contents: a—you guessed it—hurricane. It’s fantastical and creative, yet serviceable, just as the implication of a book having a wind tunnel carved into it is amusing.

It’s clear Daffy is too small, powerless, and unpredictable to stop the wolf on his own. Porky is nowhere to be found, but likely wouldn’t be of any help either—especially not for someone who prefers to just ogle wordlessly at the action instead. The forces of nature are the only reliable defense on Daffy’s side, and even then, said forces have to be invited by himself to work.

But work they do, and get a promotion while they’re at it. A cover of

The Mortal Storm (which is a film reference rather than an homage to a book, hinting at the 1940 Jimmy Stewart picture) hints at the fate brewing for the wolf that is confirmed through the help of the other books. It’s

Lightning that establishes the final straw, striking the wolf and launching him right into the air; animation of the wolf as he receives the impact is particularly crude, but is a circumstance that can spare such an expense. In a way, the crudeness translates to abstractness, which heightens the shock of the bolt and makes it seem even more powerful—it’s as though the wolf’s concept of body construction completely dematerialized with the blast.

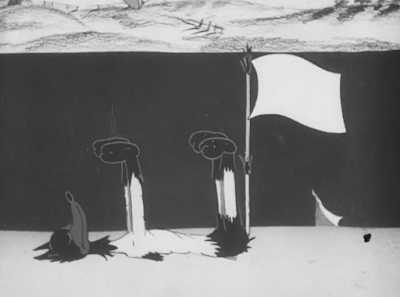

Continues crudeness in the wolf’s partially hairless corpse is juxtaposed against the solidity (speaking both of his construction and Clampett’s cinematography) of his body projected against the wall in silhouette. Cast shadows are intimidating, dark, apprehensive—we see the wolf flailing and hear his warbled scream, but we don’t see his eyes. Not knowing the full extent of his demise intrigues the audience further as they attempt to read in between the lines. Even if the shot only lasts for a few seconds.

Understanding the darkness of the situation (warranted as it may be), levity is established through having a white flag materialize on the wolf’s erect, naked tail. His surrendering is involuntarily twisted, seeing as it isn’t entirely by choice—dying via lightning strike wasn’t by choice, either. Even in still moments of darkness, the eponymous bell of

For Whom the Bell Tolls cementing the wolf’s fate in stone, Clampett’s playful sensibilities are able to eke their way in. Heaviness of the tone fogs the lighthearted spontaneity of the white flag; the disconnect is more endearing and amusing than befuddling.

Given the severity of the situation, the resolution that follows almost seems a bit too sudden. Dissolving to Daffy contented with his apathetically faced lover is a rather disarming antithesis to the simultaneous mourn-celebration of the wolf’s death. Given Clampett’s inclination to give the audience a good shock, this may very well have been intended. Regardless, there’s a lot to process in such short time. The ending resolution of the cartoon seems to be cued in rather than a natural occurrence.

Granted, we have to account for Porky in some way. Adventurous and ground-breaking, Porky finally leaves the confines of his book to check up on Daffy—any viewers anxious about how well he’ll fare outside his habitat will surely be comforted by the presence of his cowboy garb, serving as a gentle reminder of whence he came.

His delegation to second banana is once again transparent, but there’s no way to really help it. The short wouldn’t have been as sound in its identity if it were forced to wrangle around our stuttering, walking contractual obligation, painful as it may be to say. For Porky’s sake, for Daffy’s sake, and most certainly for Clampett’s sake, his shunting aside is for the best. It likewise produces an unintended consequence: returning in the cartoon only to heckle Daffy right in his face is an incredibly funny motivator.

“That eh-deh-deh-

dumb duck! He’s been weh-wasting his time around that

decoy.” Dissonance between Stalling’s syrupy, delightful string orchestration of “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride” and the chipper acidity of Porky’s words is exquisite. In chiding his companion, one almost gets the sense that he’s completely oblivious to the events that have just transpired within the past five minutes. Delegated to his bubble of moonlight campfires and cowboy songs, he’s completely oblivious to Daffy’s debatably heroic escapades, extended periods of cognizance, active awareness of the audience, and sheer conviction in his lustful pursuits.

To him, Daffy is still the duck as of

Porky’s Last Stand, whom he also condescended in the same well-meaning, perky tone. Still the duck whose barest essentials stem from making noise and jumping around, who’s too insane to grasp the (un)reality of any and all situations he’s been thrust into. He’s familiar the duck who hoohoos—not the duck who establishes himself as being on the same cultural wavelength of the audience, nor one who bears enough awareness to know to beg for mercy. To Porky, the decoy is just another momentary fixation to be forgotten about fifteen minutes later once Daffy has moved on to the next object of his continually fleeting interest.

Porky conveys all of this through more simple statements: “Everybody knows that they can never puh-puh-eh-eh-eh-

possibly mean anything t’ each other!”

Animation is certainly on the cruder side, unintentionally contributing to Porky’s own unintentionally hilarious tirade (which does seem to be intended in its lack of awareness). A chuckle preceding his words isn’t reflected in the lip sync, and perspective of his head moving around seems to have been a bit too ambitious of an idea. It comes across as a lesser animator attempting to follow John Carey’s layout work, who excelled at these types of perspective shots, only to fall short and struggle beneath such expectations. A scene that probably would have been better cast to Carey—then again, one could say that about all 7 minutes of the cartoon, his work is so appealing.

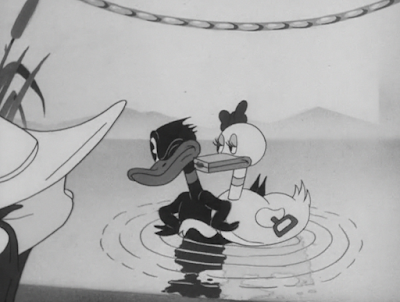

Those who assume that Porky’s spiel fell on unobserving ears are wrong. In a rare and incredible twist of fate, Daffy establishes himself as being more aware than Porky—it’s hinted through his haughty “Hmmph!”, which indicates he’s present enough to identify the inflammation of Porky’s words and take offense to them, but solidifies through the army of mechanical toy ducks following along. Porky has been bested through the most concrete proof of all.

Daffy’s little tail wag as he saunters off with his sweetie serves as a particularly attentive detail, juxtaposing against the intended stiffness of the toy ducklings. The implication that Daffy got busy immediately after the wolf was out of the picture is hilarious in its own right; especially since it inadvertently communicates that Daffy wanted to save his skin not for the benefit of remaining alive, but so that he’d be able to indulge with his "girlfriend". A worthwhile pursuit.

As if the physical presence of the toy ducks weren’t enough of a rebuttal against Porky’s words, the runt of the litter stops in its tracks to humble him further. Porky almost seems more surprised at the duck stopping to address him than the duck existing at all. Perhaps because veering off course indicates a sentience, which communicates that these toy ducklings are indeed Daffy’s offspring and not another elaborate ruse or one of his “quirks”. It’s like he’s so doubtful and patronizing of Daffy’s credibility that it takes the last possible moment to truly register that he’s been bested. The outcome adopts an entirely new layer of irony when remembering that Art Davis’

Riff Raffy Daffy would adopt a synonymous resolution, with Porky being the proud father of his own mechanical piglets instead.

Perhaps the duckling expresses all of the above sentiments with the most clarity: “

You and your education!”

A Coy Decoy is yet another on the list of shorts that I initially fell in love with upon first watch, decided I was above it as Clampett had much more interesting and engaging Porky and Daffy shorts to offer, and have once again embraced my love of it through this deep dive. I confess that this analysis is about three times longer than I ever expected it to be—Porky and Daffy just have that effect.

While it’s by no means a Porky cartoon, it again proves difficult to feel incensed about his lack of presence. While working on the color Merrie Melodies has clearly rejuvenated Clampett in some ways, he still had some progress to undergo in getting out of his rut. Concentrating on a through and through Porky cartoon probably still would have been a risky gamble at this point, as his investment in the character still isn’t exactly back to its peak. Porky’s Pooch would largely mark his return to form in that respect. Still, Daffy proves to be the more engaging foil of the shirt regarding its needs, and the cartoon is indeed better for it. He’s matured to the point where he can carry 85% of the cartoon on his own.

The line between the “old” and “new” duck is frequently toed in this short—while his growth isn’t completely objective nor linear, it does feel safe to say that

The Henpecked Duck is the short that officially christens the “new” duck. Clampett’s next Daffy cartoon after that would be 1943’s

The Wise Quacking Duck, which is, indisputably, a Daffy Duck cartoon with the Daffy Duck we all know and love. In

Decoy, Daffy’s recent developments are on full display, just as his more retroactive tendencies are. Senses of him slipping back and forth between lucidity and grounded charisma and the familiarity of gleeful hysteria are especially strong here; more subtly executed than something like

Last Stand, which is also similarly back and forth, but present nonetheless.

Decoy’s animation is more inconsistent than some of Clampett’s shorts of the time. There are some shots that are jaw droppingly gorgeous: close-up and detail shots, warped perspective and dramatic angles, shadows and silhouettes. Likewise, the short has its fair share of ugly, crude shots, many delegated to the wolf or a few distance shots of Daffy—ditto for Porky’s animation in the ending. Likewise, some of the gags seem to occur by a stream of consciousness, but such a complaint is perhaps more delegated to the format adopted by the cartoon rather than the short itself.

Nevertheless, considering that the last Clampett Porky and Daffy team up was Porky’s Last Stand—the first cartoon of 1940–this short is astounding in the growth it presents to Daffy especially. Clampett maintains themes and notes of his earlier Porky and Daffy efforts (such as Porky’s well-intentioned, clueless patronizing of Daffy), but the tides are certainly turning in who gets the most directorial attention and even sympathy. Last Stand has its share of sympathy regarding Daffy, but obstructed through the desire to laugh at his impulsivity first. Here, even in spite of his brashness (and even creepiness), he is genuinely made out to feel sympathetic. We pity his attempts to stave off the wolf, we celebrate his “win” at the end of the cartoon. He isn’t just an afterthought of wacky comedy relief.

Indeed, while better shorts are out there, whether from, before, or after 1941, A Coy Decoy will always be a short I am fond of at the very least. Daffy’s evolution is rewarding to track and celebrate, Porky is endearing and charismatic in his limited screen time, indulgences taken by Clampett are fun and supportive of his directorial vision rather than actively weakening his material. It’s an easy impulse to deem this short the lesser pig and duck team up of 1941, as The Henpecked Duck is such a solid short (as we will soon explore), but it still presents a lot to admire and love, any warts and all.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment