Disclaimer: This review contains racist content and imagery for historical and informational context. I encourage you to speak out should I accidentally say something that is harmful, perpetuating or ignorant--it is never my intent and I seek to take accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: June 7th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Gil Turner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Hiawatha)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

That the fourth Bugs Bunny cartoon is the second short to receive an Academy Award nomination is certainly indicative of his success as a character—even if it took a mind boggling 18 years for him to actually win an Oscar.

A Wild Hare being the first nomination just makes sense. The first “true” Bugs short, the world had truly never seen anything like him or that cartoon before. He was one of animation’s big bangs. However, learning that this cartoon received a nomination is almost a bit of a head scratcher.

That’s not to call this cartoon bad or dismiss it by any means—it certainly is not. That rascally hindsight bias strikes again; it’s so easy for us to think of countless other Bugs shorts from all years that could potentially be more deserving of a nomination than this short which, while still amusing, seems totally domestic 82 years later. One has to remember that the novelty of this rabbit was still incredibly fresh, and would continue to be for years. This seemingly innocuous hunter vs. rabbit team up, spoofing both Henry Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha and the 1937 Silly Symphony that followed, was once a brilliant display of subversion and charisma. It becomes all too easy to take for granted the grip Bugs had, especially early on. Anything with him in it was bound to impress, especially in the landscape of 1941-and-before cartoons.

It is now Friz Freleng’s turn to get acquainted with the rabbit, with writer Mike Maltese at his side. Once again, both men are responsible for a number of developments and refinements to the character that would define how the public interprets him for years to come. Almost to an iconic degree, seeing as their respective visions would split in later years; Freleng was a purveyor of Bugs’ mischievous spirit (“I don’t ask questions; I just have fun!”), whereas Maltese—in collaboration with Chuck Jones—was partly responsible in removing the rabbit from his wily Brooklyn roots and embraced the role as a world weary suburbanite.

Of course, this all remains years in the future. For now, we step into the mindset of artists and audiences as of June 7th, 1941, mingling with the much more hardened, impish, abrasive Brooklynite rabbit whose heckling is an everyday pleasure rather than an obligation or necessity. Upon learning of Longfellow’s poem in which Bugs is slated to be Hiawatha’s victim, he decides that having fun with his captor-to-be is the best course of action.

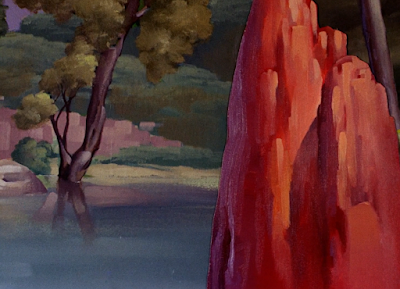

No doubt the picturesque visuals in this cartoon are partly responsible for its Oscar nomination—being derivative of a Disney short entails aping the saccharine visuals therein, which Freleng and his background painters do very well. The lushness of the backgrounds—salmon, rocky mountains, clear, blue waters, white, foaming waterfalls, crisp green trees, gentle reflections cast in the water—is absolutely earned and the product of a solid technique and visual rather than a mere copycat of the Disney philosophy. Still, deceptive saccharinity of the opening is entirely intentional, and the sanguinity of the Disney cartoon certainly played a part in informing the visuals here.

Orchestration of such consciously picturesque visuals and Stalling’s trickling, hopeful, serene musical arrangement serves not only to impress, but to be dispelled. The juxtaposition between the beautiful nature and the abrasive, carrot-chopping, nasal strains of Bugs’ voice obtusely cutting in on top is absolutely perfect. Even if a theatergoer in 1941 had missed the development of this new rabbit sensation, with this short being their first introduction to the enigma, they would immediately know that the source of this voice is completely out of his element. We don’t have the privilege of attaching a face to a voice—his narrations are entirely off-screen—but the dissonance is incredibly tangible.

Even the structure of the cartoon is purposefully concocted in the shadow of Disney to poke neighborly fun—both shorts open to a narrator reciting Longfellow’s poem atop visuals of Hiawatha in his canoe, paddling past tall waterfalls and through winding rivers. Of course, Bugs Bunny is no velvet voiced Gayne Whitman; his descriptions of boich canoes and fores’s and mighty Hiawat’as strikes a tone that is proud in its unabashed sardonicism, immediately discrediting any illustriousness in the background paintings, music, or other tranquil notes of an atmosphere.

Hiawatha’s entrance is much more stolid in comparison to the Disney cartoon, too, merely popping out from behind a strategically placed rock in the foreground. The simple, horizontal camera pan communicates a bluntness that is far removed from the more intimate, twining, diagonal angles of Disney’s introduction. There’s also the specificities of Hiawatha’s appearance—his scowl and bulbous nose are the complete, grisled opposite of Charlie Thorson’s cuddly design work. Freleng’s Hiawatha serves as the perfect indication of the reigning Warner identity; trademark Disney cloyingness is demolished through a purposefully overcompensatory aggression and irony that communicates mischief and rowdiness over plain disdain.

A shot of a stolid faced Hiawatha scaling down a series of waterfalls, canoe melding to their stair-like construction with amusing ease, is yet another take-off of the Disney cartoon, where Hiawatha hitting a slight bump in the water is grounds for additional cavity inducing character acting. The “water stair” gag here is nothing new, to Warners or otherwise—some of the earliest Warner shorts boast this very gag, including 1931’s Hittin’ the Trail for Hallelujah Land (which Freleng himself animated on.)

Nevertheless, antiquated as the visual may have been even in 1941, its purpose isn’t entirely dependent on getting a laugh on the surface alone. Rather, to poke fun at Disney’s example and how comparatively overacted it is—the scowl as Hiawatha obediently traverses down the steps without a second thought is yet another grisled antithesis to the blinks and bumps and tumbles of Disney’s Hiawatha over the tiniest change possible.

Dissolve to the source of the commotion. Maltese and Freleng unknowingly institute a springboard for many Bugs cartoons to come—Bugs spending his time lounging, reading a book in all of his inarticulate, often borderline illiterate glory, only to either take issue with its contents (such as Freleng’s Rabbit Transit, the third and final entry in the tortoise versus hare trilogy) or laugh them off entirely and have said contents of said book bite him back (as is the case with Bob Clampett’s Falling Hare.)

Dick Bickenbach has the distinction of animating the first Bugs in a Freleng cartoon. This is both to his and Freleng’s benefit, as this short is clearly indicative of the crew getting their sea legs when it comes to understanding how the character looks and acted. A particular emphasis on the first part, seeing as Bickenbach’s Bugs is incontestably the most attractive rabbit the short has to offer. He maintains a cute appeal, particularly through his big eyes and ears—nose isn’t too big, head relatively solid. The manner in which Bickenbach moves his characters proves plenty helpful as well, whether it be the quirk of his trademark eye blinks or his nuances in timing. Comparing his rabbit to scenes with Gil Turner or Cal Dalton’s work is night and day.

In any case, Bugs continues to amuse himself with his book as its prophecy unknowingly folds behind him. Even the book itself is labeled “Little Hiawatha”, which is the exact title of the Silly Symphony. While it’s more probable that the name is just easier to write out and communicate on a moment’s glance than “The Song of Hiawatha”—as well as communicating further notes of antithetical saccharinity through adjectives such as “little”—the Disney reference is certainly not lost.

This is a cartoon that gains a lot of mileage out of proud incongruities and subversions; even Bugs’ reading isn’t accurate. In the Disney cartoon, Hiawatha’s actions coincide with every word of the narrator. Twining through the canyons with its bends and shadows, through the falls of Minnehaha, and so on and so forth. Here, Bugs repeatedly mentions Hiawatha’s attempts to ready his “trusty bow an’ arruh”—the audience will take note that the absence of such a bow and arrow is entirely purposeful. While the story chronicles Hiawatha settling in for a kill, again mentioning his bow and arrow, eyesight keen, the real Hiawatha paddles through the river. His purposeful disregard for the story is a joke in itself.

It takes Bugs not once, but twice to read the line about slaying the forest rabbit to realize he’s a forest rabbit. Tortoise Beats Hare’s influence is palpable—a synonymous slow burn and explosion of realization transcends here just as it did in the former, if not quicker. While he doesn’t have a title card to tear into pieces, he does turn into a blur of an afterimage, rushing around in an aimless panic. A novelty when juxtaposed against the established Bugs of the present, who would seldom ever engage in said aimless panics; especially without having met his adversary first.

Details of his book and some tree leaves rushing off screen in the wake of his outburst are just a few beats too late, occurring just before the dissolve wipes it all away. Regardless, it serves as a cute, attentive topper that enunciates the ferocity of Bugs’ departure. One doesn’t get the sense that he’s rushing to hide—rather, that he’s preparing to intervene.

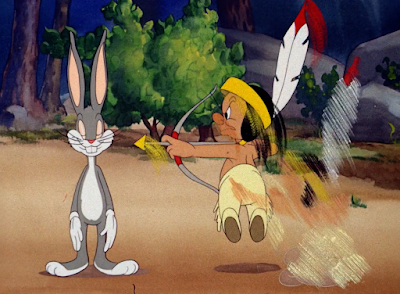

Which, judging by Hiawatha’s mannerisms, may not be so difficult to do. Bickenbach’s animation extends to the formal introduction of the hunter, who—like Bugs—is constructed in the influence of Tex Avery. His nasal, dopey vocal stylings, repetition of words, and affirmative “Yeah-yuh, yeah-yuh!”s are clear nods to Avery’s fixation on similar archetypes (ie. Lenny from Of Mice and Men.)

The enormous cooking pot towering next to him is indicative of his intentions. Thus, with bow an’ arruh at the ready, he sets out to nab a rabbit…

…which offers rife opportunity for further Disney spoofing. Both the tottering walk and the trips that soon follow seek to rib the Silly Symphony of its repeated attempts to endear the audience through such fodder; here, a sense of near ridicule prevails over any sort of endearment. Freleng’s musical timing comes in clutch for Hiawatha’s falls as he trips into dirt, each timed with an abrasive drumroll that communicates snappiness and humor over any cuteness. Even if one weren’t acquainted with the Disney cartoon, the timing and rhythm is enough to amuse. (Knowing it’s a knock on Disney does make it just a bit sweeter, of course.)

Suddenness of discovering rabbit tracks is yet another gag in itself—the convenience of the tracks is much more forward than the same instance in the Disney cartoon, where Hiawatha stumbles upon “grasshopper tracks”—essentially a means to milk further saccharinity. Freleng’s Hiawatha has no time for such nonsense. Neither does Freleng himself.

Indeed, Hiawatha’s furtive sneaking is about twice as fast and abrasive than anything in the Silly Symphony. Camera movements following the hunter are almost violent in how sharply it jerks to follow his footsteps; the effect is striking in motion, conveying a determination, aggression, and conviction that both supports what little threat Hiawatha poses to Bugs and diminishes it through how playful the maneuver is. The camera movements and directing are bigger than he is.

A switch in animators is certainly noticeable in the scenes that follow. Simplicity and admitted crudeness in Hiawatha’s design at a distance is the first indication, but the handling of Bugs—revealed to be basking in the stew pot that now miraculously has water in it—clinches it.

Such is the work of Gil Turner. His animation work has certainly improved since his earlier days in the Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton unit, regarding both draftsmanship and motion. Still, it remains easy to spot his handiwork; there isn’t much of a sugarcoat to be had other than “Bugs looks ugly”.

While he gaily sings a tune of “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano”, using the pot as a bath, Hiawatha takes the opportunity to kindle a fire. No bow an’ arruh necessary.

In spite of breathing “Boy oh boy—rabbit stew at last,” Bugs still remains oblivious to his intentions (condescending him through the name of Geronimo, leader of the Bedonkohe Apache) and even goes as far as to help him. Having Bugs get too wise too early would dash Freleng and Maltese’s plans of a long-winded gag—rest assured that this goes on for nearly a minute more.

Bugs lowering himself into the pot benefits from serving as a launchpad for future, more memorable instances—the same flinching and gradual easing in would be seen in cartoons such as A Witch’s Tangled Hare, one of a handful of shorts directed by Abe Levitow. Unsurprisingly, Maltese boasts a writing credit on that cartoon as well. Granted, that short was released 18 years after this time, with plenty of time to refine not only Bugs’ personality and mannerisms, but the flow and pacing of action. The charade goes on for a bit too long here, but there isn’t much of a need to rush—especially if the joke hinges on Bugs taking too long to get settled and behaving much more like a human than an animal being boiled alive.

Nevertheless, his “bath” proves to be more relaxing than not—especially with the benefit of room service. Rather than digging around in the pot for any of the sliced carrots that Hiawatha cuts into the “broth”, Bugs skips the trouble and takes the carrot right out of his hand. An act of casual pretension and entitlement that is amusing through its innocence. That, too, is aided through Hiawatha’s quizzical stares; instead of getting mad at him, he just cuts up another carrot. He’s written to be a bit of a dope, but has enough brains to know that upsetting his dinner won’t do him any favors.

The first “what’s cookin’” (with “chief” substituting “doc”) uttered from Bugs’ mouth is, ironically, in a literal setting. A by the books dialogue exchange ensues—Hiawatha detailing his plans for a rabbit stew, Bugs remarking he loves rabbit, realizes he’s a rabbit. It’s easier to dismiss such a sequence as predictable in the year of 2023, since so many synonymous scenarios have followed. Every cliché had to start somewhere. Blanc’s charisma in his deliveries for Bugs are timeless, and the lightly airbrushed backgrounds to convey a depth of focus really elevates the scenery a lot. There’s certainly still much to appreciate, even if the gag itself has gotten old.

It should be noted that even as of 1944, such a sequence was regarded as old hat. Bob Clampett’s What Cookin’ Doc memorably implants footage of this cartoon into its story, serving as Bugs’ argument as to why he’s deserving of an Oscar. That this short was nominated for an Oscar certainly helps in the choice, but the gag also seems to be that it’s a deliberately stale and unfunny slog, making him even more undeserving of an Oscar. It could be argued that the nomination was the only reason they chose it and not friendly fire; that argument loses water when remembering A Wild Hare received a nomination as well.

By 1944 (and today especially) the bit is relatively stagnant, but is somewhat comfortable in the climate of 1941 cartoons. A bit too long and slow, perhaps a little too clueless for Bugs even then, but remotely serviceable nonetheless. It does prove difficult not to think of the tinny, feverish arrangement of “Merrily We Go Along” and the accompanying shot of Bugs mooning the audience after he jumps out of the pot, however.

Animation of Bugs finishing his take is a little on the slow side—too many drawings that are too evenly spaced apart—but that’s more a product of his retreating into a hole firing on the slower side. Again, the burden of hindsight is mainly to blame. It proves difficult not to think of a dozen synonymously frantic exits that are twice as fast and furious. The information is clearly conveyed, and that’s arguably the most important objective: the stakes just don’t feel as high as they possibly could, especially nearing the short’s halfway mark. This is the second time Bugs has identified himself as a target and fled off-screen in the short now, so some payoff or change would be nice to see.

Thankfully, Bugs swan diving into a hole for refuge does shift focus onto a new set of gags: Hiawatha firing into the whole, which is revealed to be an elaborate pinball setup through a smattering of adjacently placed holes. The bright, neon lights and plinking sound effects prove a stark contrast to the quietude of the wilderness—thus, the success of the gag is cemented through how alien and out of place it is intended to feel. A gag that rides on its notes of newfangled-ness thrives well in accordance to Bugs, who is pretty newfangled himself—the visual is brazen and modern, just like he is.

Cementing as such, Bugs pops out of the whole with a neon “TILED” sign—for those unaware, a tilt in a game of pinball refers to the tilt sensor within the game. A device intended to prevent and discourage players from cheating, a machine will tilt if the sensor has been activated enough to suspect any pinball chicanery. Thus, all operations of the game shut down, resulting in a loss of points and even the end of a game.

In other words: further humiliation for Hiawatha, whose recipience of a kiss on the cheek seeks to assault any masculinity he has. For Freleng’s first Bugs cartoon, he’s certainly studious of the machinations pertaining to Avery’s rabbit.

That includes the analyzation of an overzealous ego. Riding on the high of embarrassing his captor, Bugs engages in a particularly grandiose dive back into his hole. His business is done here. Such a performance communicates finality; there’s no room to argue who is on top in that moment. Bugs is king.

Except for when he isn’t. Misjudging his aim, he instead crash lands right into the dirt. An amusing ego check that is almost shocking in hindsight for those aware of the rabbit that never loses, the rabbit that faces no folly. Any invincibility in the earliest cartoons manifested in a mental mindset rather than the actual forces that conduct the cartoon. Bugs is not as untouchable as he believes.

His viscerally ashamed reactions are indicative of a period where the character was still getting his sea legs—the tail behind the legs look is funny, accentuating how the blow is almost bigger emotionally than physically, but isn’t entirely fitting for his character. Nervous chuckles, grins, and blinks as he makes a futile attempt to save face would be more in such a wheelhouse. Still, it’s incredibly early.

Nevertheless, one trait of Bugs’ is for certain: resilience. An undisclosed amount of time is ushered through with a fade to black—could be minutes, could be hours for him to have ruminated on his public humiliation. He’s come out of it on the other side in any case, readying further insults to Hiawatha’s integrity as he fools with a rope.

An invasion of Hiawatha’s personal space indicates a further disregard for any dignity he may have. His tone is low and casual (moreso than usual), which communicates a condescension in its own way.

“I’m gonna take dis rope, an’ I’m gonna tie you up!”

Zipping out of Hiawatha’s direction prompts a series of befuddled head shakes as he speaks into the air. Freleng’s subtle charms have always played a great benefit in his Bugs cartoons, and here is no exception—such a comparatively small, insignificant maneuver, but one that adds a lot to the dynamic. Bugs is made even more brash and insensitive, Hiawatha more befuddled and slow.

Similar to the boiling pot scene, the exposition teeters on the more belabored side. Granted, the build-up is the strongest point of focus; it offers further opportunity for Bugs to ridicule, heckle, and leave room for his ego to get checked once again. The end “resolution” of him actually being tied up isn’t nearly as worthwhile as the events that lead to it, which Freleng seemed to grasp. Bugs can’t cackle and laugh in Hiawatha’s face or slap him amidst his hysterics—again, behaviors somewhat a novelty in themselves through how reckless they are. Daffy would be a more prime candidate for such inadvertent, insensitive aggression; Bugs is more the “snicker from afar” type.

Bugs’ hysterics do provide the benefit of Mel Blanc’s continuously fantastic voice acting—his cackles and shrieks and laughter are all genuine in their intoxication. Facetious as Bugs’ behaviors may be throughout the cartoon, the ferocity of his laughter and heckling is very, very sincere and motivated.

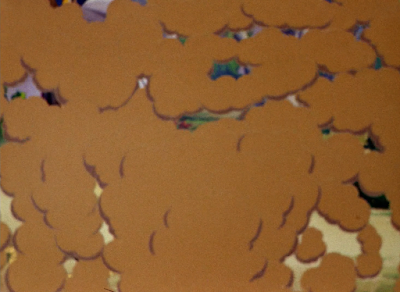

As is Hiawatha’s desire to have rabbit stew. The scuffle that ensues is obscured through a sheen of dust kicked up from the fight; vocalizations are scarce, with only Stalling’s intense music score and the rummaging of feet offering the only verbal cues, but remain illuminating enough to get a picture of what’s going on.

Handling of the dust dissipating does suffer from a dissonance, but may be out of slight necessity—as the dust clears, neither Bugs, Hiawatha nor the tree are visible in spots where they should be. Such seems to be a preventative measure in obscuring the payoff until the last possible second: Hiawatha tied to the tree with a contented Bugs admiring his handiwork. If the under image were visible beneath the dust cloud, the timing of the punchline would have been skewed and thusly felt less rewarding. The ways in which these bursts of effects animation are handled would continue to improve throughout the years, just as they have to get to this point now; similar “dust reveals” would produce the effect desired by Freleng. For now, the disappearance of all of the subjects is an adequate cheat to meet his needs, but somewhat jarring nonetheless.

The dust cloud also seeks to disguise a switch between animators. Now, Cal Dalton takes the helm; while his animation in the Freleng shorts is usually solid, his Bugs poses some problems against the reigning styles and interpretations throughout the cartoon. Nose too big, ears too far apart, teeth too long—he looks a bit like a hybrid between the current Bugs Bunny of 1941 and the last Bugs Bunny he worked with in 1938 and 1939 with Ben Hardaway.

Again, expecting each Bugs to come out of the gate completely perfect is just not possible. Including Freleng, this was the first time anyone in his crew had worked with the new Bugs Bunny—there’s bound to be dissonance. Evolution isn’t called evolution because it happens instantaneously. Growth takes time; that’s why it’s being noted. Bugs has become such a beacon of perfection the way we know him, which makes it all the more fascinating to track any inconsistencies or mistakes or quirks in his earliest days. It’s not as though anyone had insight regarding what the character would become. Especially not after his fourth cartoon out of nearly 200. Any nitpicking isn’t so much a slight on the artists and directors in the moments as it is a commentary, comparing the old to the new, the refined to the rough.

For a short release in 1941 that hinges on Native American stereotypes, the stereotypes in question haven’t—to this point—been as pointedly abundant as others. That it takes nearly 5 minutes for Bugs to engage in a war chant and further mock Hiawatha is almost impressive, given how cartoons constructed in a synonymous vein are so quick to engage in the broken English, the defamatory language, and so on. The bar is quite low.

Eventually, Bugs’ dance amounts to him bouncing on his butt and engaging in a conga that takes him away from the screen. Both are indicators that he isn’t taking any of this seriously—a given throughout the entire cartoon, but he can’t even fully commit to his heckling without having to demonstrate that he’s completely above it all.

His exiting of the scene is not only to demonstrate that his time caring about Hiawatha—in that moment, mind you—has expired, but also serves as a mean for him to weasel into his next appropriating disguise. Predictably, that falls more into the realm of the stereotypes listed above.

Seeing as disguises are a core aspect of Bugs’ trickery, it should be noted that, unless counting a sequence where he dresses up in a dog suit as his prototype self in Hare-um Scare-um, this is the first instance in a true Bugs cartoon where he uses a tried and true disguise to fool with his adversaries. It again becomes easy to compare to later instances; this whole bit of him giving Hiawatha false directions as to where the “little rabbit” went and then remarking on how dumb he is would have been three times as fast in future endeavors.

Such is a consequence of establishing his personality—audiences in 1946 didn’t require an elaborate explanation that its really Bugs hiding in a disguise the whole time, don’t worry, he’s still here, look at the funny disguise. While there is no doubt in anyone’s mind (save for Hiawatha) that this is Bugs here, Freleng pumps the brakes a little and allows both Bugs and the audience to fester in this new, novel idea of impersonation for personal entertainment and self preservation. Namely the former.Droning drum rolls in the background indicate Hiawatha’s presence, the percussion growing louder as he looms closer. A smart act of association that instantly enables the audience to recognize him, as well as giving some tangibility and depth to his appearances off screen. Just because he isn’t in frame doesn’t mean he’s completely gone from the collective conscience.

With Hiawatha out of his hare hair, Bugs is free to have a private moment with the audience. Drawings once again teeter on the crude, relatively unappealing side, but his character acting itself is charismatic and supportive of his line deliveries. Head tilts, gestures, nods, a cross of the arms, points, winks; they all feel indicative of the cool, alluring conceit that is Bugs Bunny. A motivation guides his gesturing and movement—not obligation to stock acting tropes as a means to engage the audience.

“Imagine a joik like dat tryin’ ta catch a smaht guy like me.”

Imagine no longer. The wilting of his ears is a particularly nice touch—a physical manifestation of his wilting ego as his conceit leads to his ignorance yet again.

As though he refuses to believe he’s truly been cornered without solid evidence, Bugs feels up the arrow pointed at his head while averting the gaze. Pricking his finger on its sharp tip is the nail in the coffin—he’s been had. It’s certifiably an arrow.

Freleng’s experience relating to marrying musical timing and extreme caricature on The Trial of Mr. Wolf pays off well in this next bit. Bugs hops mechanically away from Hiawatha, who follows him. That’s followed by two hops, then four, and so on and so fourth. Each bout of hopping quickens in pace, nestling deeper into Stalling’s rhythmic accompanying tune—it quickly evolves into a flurry of motion and music, prior music fragments amounting into a fully-fledged accompaniment piece that seems planned from the start. The animation, the music, and the tone are all gleefully spry; much of the humor stems from how wholly artificial the movements seem to be, how exaggerated and caricatured they are. Very well timed and executed for a gag that seems to celebrate its trivialism.

Of course, it isn’t entirely for naught. The seemingly “visual noise for the sake of visual noise” amounts to a payoff, with Bugs conveniently landing on a tree branch strategically hanging off of a cliff side. A calculated but brazen move—there’s a cockiness in his assumption that the twig would be waiting for him. Smears and multiples increase the intensity and motion of the drawings, which proves helpful in encouraging the youthful spring in Bugs’ every step. Such renders him all the more lively.

Not to be bested by his dinner, Hiawatha sets out to do the same. Differentiating his and Bugs’ accompanying motifs through varying octaves is a creative, attentive choice that gives a longevity and permanence to their actions. It lends the action to less risk of monotony or repetition, as well as conveying additional weight (or lack thereof, as the higher cues for Hiawatha makes him feel lighter) outside of just the animation.

If Bugs is able to find security on a flimsy tree branch, then Hiawatha—cast as his foil—is doomed to fall. His frozen, petrified reactions as he stands in midair are familiar to many a casual viewer of Warner cartoons, and even at this point it wasn’t an entirely new visual. One recognizable nonetheless, and enough for audiences of both 1941 and 2023 alike to rejoice in their knowledge that he won’t be suspended in midair for long.

Transforming into the visual image of a sucker, coinciding with Bugs’ taunts, is also not new; Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton were the first to introduce it to the Warner cartoons starting with 1939’s Gold Rush Daze. It, too, is a gag whose punchline and intent remain timeless in their understanding.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

This the second time bugs bunny put on one of his disguises. "Hare Um Scare Um" (1939) was the first and I don't care what people say, and I don't care if he was different in that cartoon.

ReplyDelete