Release Date: June 21st, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Announcer, Horse)

(You may view the cartoon here!)While it isn’t exactly related to the contents of this review, I’d like to preface this particular analysis with an important footnote in Warner’s history I neglected to mention around a closer time in which it occurred. Since said event partially pertains to Chuck Jones’ involvement, I figured this review would be as good as any of a selection:

In 1941, the landscape for Leon Schlesinger Productions was looking up. They not only had the benefit of one of the busiest release schedules on record, but a release schedule that released good—if not great, if not groundbreaking—cartoons. Two of their cartoons that were released that year were nominated for Academy Awards. Murmurs of the rascally, carrot chewing rabbit were rippling into conversations. Cartoons continued to get faster, funnier, fresher, the still youthful medium of animation steadily evolving. Many of the shorts released throughout 1941 began production in 1940, meaning that the artists of Termite Terrace were creating even better, even brasher, even greater cartoons that would spur similar ripples of excitement the following year. After a brief dip in quality at the turn of the decade, everything finally seemed to be looking up for good.

Too bad that wasn’t entirely the case.

As great as the cartoons may have been for their time, there was a slight simmer of turmoil behind the scenes. Leon may have been a solid businessman, understanding that it was best to allow his artists to do their own thing, but he was still a businessman—a notoriously cheap businessman. That extended to the quality of the building in which they worked in (as many interviews from Warner alumni can attest to) and, unfortunately, the pay.

Ink and painter Martha Sigall recalls that the rightful unhappiness with low pay and stagnant salaries resulted in the formation of an underground union. Inkers, painters, inbetweeners, assistants, painters, carpenters, animators, background painters, layout artists—the latter three rallying thanks to Chuck Jones, who was by all accounts proudly pro-union and a great force in unionization efforts—and even a handful of directors all rallies together to organize. In Sigall’s words: “Chuck definitely had done the most to get the studio organized.”

|

| During the lock-out. From left to right: Ben Washam, Roy Laupenberger, unknown, Sue Dalton, Paul Marron, and Martha Sigall. Photo taken by Chuck Jones. |

Word on the street was that employees over at MGM had signed a union contract without much fuss—certainly an optimistic sign. Thus, with this in the back of their minds, nearly all of the Schlesinger staff went to haggle with their boss.

I trust you can guess his answer.

Not only did he give his rejection, but had the privilege of allowing his attorney to lecture the staff like a group of delinquent school children. “This had a tremendous uniting effect on us,” recounts Sigall. “We held a meeting at union headquarters, and Chuck gave us an inspiring pep talk.”

The only logical course of action was to strike. Thus, sometime in May 1941, the studio engaged in a six-day lock out—Leon locked the staff out of the studio, which, in Sigall’s words was almost more beneficial than a formal strike. “In its way, this was a great thing for us, for, if we had gone on strike, we would not have been eligible for unemployment insurance pay. Being locked out gave us that eligibility.”

It should be reiterated that the lock-out only lasted six days, seeing as Leon finally succumbed to a new contract. Historian Tom Sito accounts in his book Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson that, when signing the contract, Leon quipped “Now, how about Disney’s?”

He got his answer starting on May 29th, 1941.

While the Warner lockout serves more as a footnote in its history compared to the ramifications of the Disney strike, which altered the course of the studio’s history as we know it today, it still remains important to note. Due to the cheerfulness and joviality of the cartoons produced, it becomes an easy tendency to assume that behind the scenes is just as amiable as what’s on the screen—that is unfortunately seldom the case. Regardless, it’s illuminating history to know whose loyalties lie where, how that impacts the trajectory of their career, the medium of animation, the legacy of their work, and so on and so forth. Porky’s Prize Pony was produced long before the lockout, but is still interesting to know that the happy, smiley, Disney-esque antics on screen follow just a month or so after turmoil and unrest that had been broiling for years.

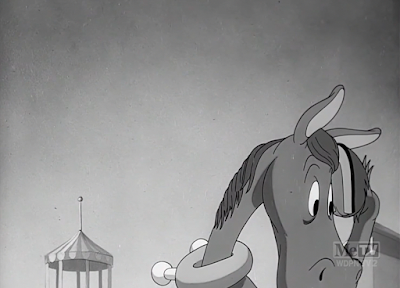

The backstory behind Porky’s Prize Pony is much less interesting and illuminating—that’s because there isn’t really much of one. However, one would be remiss to ignore the design similarities between the horse in this short and Jones’ The Draft Horse the following year; Draft Horse is often regarded as the turning point of Jones’ directorial career, his first tried and true comedy that is synonymous with the reigning Warner tone. Something particularly intriguing to note when this cartoon still establishes its ties to Jones’ Disney influence.

Back in the saddle in yet another “Porky horse racing cartoon”, the spotlight is much more sympathetic to the eponymous prize pony. Having been kicked out of the barn, the horse spots a jockey Porky preparing for a horse race, and immediately imprints upon him in hopes he’ll be adopted. Porky repeatedly demonstrates he has no such plans… until an mishap calls his racing hopes into jeopardy.

No time is wasted in establishing the crux of the short. This being another pseudo-pantomime effort from Jones, information is introduced primarily through context clues. There certainly is no greater context clue than a camera pan ogling at the pompous, large banners heralding a $10,000 reward for a steeplechase at the county fair.

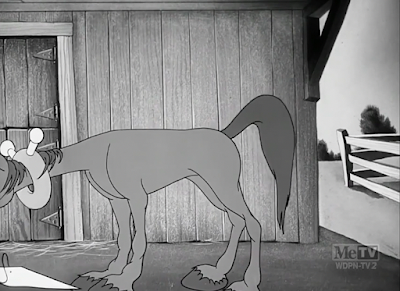

Likewise with the camera settling on a stable that brands itself as elite. The “KEEP OUT” lettering extends not only to any curious, decidedly non-elite jockeys or the general public, but a particularly dopey, soft horse that is booted from the premises. The timing of its expulsion is particularly sharp, especially for ‘41 Jones—the maneuver is weighted, urgent, and playfully alarming. Indicative of future endeavors with a more speed conscious, abrasive Jones.

A “no horses wanted” sign is slipped through the cracks of the door at the last second—while the branding of the elite stables and the giant “KEEP OUT” is certainly enough to identify the horse’s supposed trespassing, the last minute addendum of a sign serves as further insult to injury. Without a word said or even a thorough glance at the horse’s face, the audience grasps the conflict with ease. Jones’ directing is clear and concise, but not to the point of condescension by spelling every little thing out. An organicism lingers in his delivery to make the viewer feel as though they’re piecing the clues of a puzzle together rather than having information shoved down their throat they didn’t even ask for. A sign of a good director.

Of course, clarity doesn’t exactly absolve Jones of his Jones-ian tendencies. Pacing is still bloated at times in this short, lingering on bits that he likely found much more amusing than the audience. The first glimpse of such an instance occurs through the horse ogling at the audience—jutting his neck out in protest prompts a flurry of visual activity with his mane, which soon becomes his (and Jones’) plaything for the entire short. Moving and rearranging and fidgeting with the hair that constantly droops over its face. It’s a smart way to give him a vulnerability, which Jones was always inclined to do (little characters fidgeting with their big hats, characters who constantly trip over themselves, and so on and so forth), but is harped on one too many times to be immensely entertaining.

His hair swiping here does herald a purpose, however; it clears his line of vision, which allows him to spot another, more modest stable that has a better chance of accepting his ilk.

Enter Porky. If the “PORKY PIG’S STABLES” sign stop said stable that is more akin to an outhouse isn’t illuminating enough of his presence, then his voice atop the screen is. Most of the short’s dialogue accounts for his homely chorus of “We’re in the Money”, fashioned into “I’m in the Money” with lyrics endearingly morphed to be more horse-racing appropriate.

This twenty second song number is one of my favorite sequences to come out of Jones’ “saccharine era.” In short, it looks, sounds, and is adorable. Cute in a way that feels completely organic rather than truly forced—no coy blinks or bloated beats or any other type of forced vulnerability. Porky tying the racing tape around his horse’s leg and casting a very brief glance up at his steed is executed with a particular grace and naturalism that truly feels like a subconscious impulse rather than a forced gesture.

Moreover, kicking the tape away upon his lyric of “I’m feelin’ cocky,” is a wonderfully conscious pairing, as it enunciates his chipper mood. While having proven himself to be excitable just like everyone else, he isn’t a character who regularly indulges in something as “reckless” or carefree as playfully kicking something out of the way when he’s done with it. There’s a blind faith that comes in such a maneuver. Trusting that you’ll throw the tape with enough accuracy for it to find your foot, which must also propel it in a satisfactory manner to effectively discard it. It’s a quaintly mischievous gesture that isn’t always Porky’s default, and especially not at the beginning of the cartoon. His good mood is palpable.

Of course, the success of the song doesn’t hinge on the groundbreaking revelation that Porky kicked something. Blanc’s vocals are charismatic to the eleven, matching the jovial warmth of Carl Stalling’s accompanying music score. The animation and character acting, as previously harped on, is charming, believable, and motivated. Intentions of the scene are easily conveyed through visuals and context—the plethora of ribbons and trophies in the background indicate that Porky’s bragging in the song lyrics aren’t without justification. Paul Julian even goes as far as to paint the initials “P.P.” on a horse blanket in an incredibly tiny, out of the way photo, again confirming Porky’s success. Such a minuscule detail adds so much.

An over abundance of detail can be just as charitable, too. Porky’s race horse is much more akin to a real live horse than anything touted by the eponymous prize pony. Such a disconnect in designs allows Porky’s horse to feel stronger, more stolid, more “professional”—it justifies his racing success, just as it enunciates the dopiness of the other horse and establishes the standards set by the fair and its steeplechase. In short, he isn’t up to snuff.

Even cute, diminutive Porky thinks so—upon his encounter with the pony posing at the ready outside of the stables, asking to be taken home, his immediate impulse is to laugh at him. There’s a sort of endearment behind his wheezing, poorly contained chuckles, as though he’s genuinely amused at the pony’s charade and self advertisement rather than mocking him out of complete degradation.

To be fair, there’s a lot to laugh about, especially in Porky’s position. Jones’ humanization of the horse proves ripe for humor; while Porky’s laughter stems from the physical attributes and overall dinkiness of the horse, polite amusement is delivered to the audience through the pony’s sense of preparation in being adopted. The sign dangling from his mouth reading “TAKE ME HOME. FREE!” adopts a stronger awareness through the period after “home”—casting “free” as its own separate idea introduces an added incentive. Even if Porky doesn’t want or need the horse, the pony rides on the hope that the principle of a bargain may be enough to win him over.

And, as if he even anticipated that to fail, the pony offers other additional means of back-up through further signs. Great condition, even a stamp on his hoof that heralds the approval of “Good Horsekeeping” (kudos to Rich Hogan on such a simple, stupid, and successful pun). Keen eyes will note that as the horse bends down to retrieve his second sign, the wooden ring slides down his spindly neck—another way to communicate his vulnerability and dopiness.

One final sign bragging about his role as a good show horse is probably a bit more than necessary. Following the rule of threes, the close-up of the hoof would have been a comfortable spot to transition to the next idea—it ends on a solid punchline that differentiates itself from the two preceding gags. Tacking on another sign after the fact seems to enable the air to leak out of the momentum just a little, registering as overkill. Then again, the whole point of the sequence is to spotlight the horse’s overcompensatory nature, furthered through the affirming nods as he boasts the sign in his mouth. It’s just a bit too much in a way that Jones didn’t seem to intend.

All of the above critiques are maintained through a relatively slogging vignette highlighting the horse’s attempts to show off just what a great show horse he is. The zeal in which he scrambled to jump into a new position is strong, rightfully hurried and energetic, offering a powerful juxtaposition against the purposefully slow and plodding movements that follow. Still, the horse struggling to keep his tail erect falls in the philosophy of him constantly moving his mane out of his eyes (which he does here as well.) Amusing once, indicative of personality and intent of his vulnerabilities, but soon grows tiresome. Especially when the bit lasts for half a minute. Nevertheless, the posing of the horse is strong—a frequent benefit throughout much of the short.

Like the audience, Porky has grown weary of the horse’s “tricks” too, as the next shot of him is him walking away from the horse. He has more fulfilling ways to spend his time.

As do we. Conscious of this, momentum shifts to the antics ushered in by the horse following Porky—a pattern that is adopted by the majority of the cartoon. Preceding his hounding, the horse engages in a mild wind-up of momentum to pursue his hopeful owner-to-be. In the process, he loses one of his horseshoes. Another clever and attentive detail to convey his endearing faults and vulnerabilities. Unfortunately, the action is easily lost in the excitement of the horse following Porky and doesn’t exactly register. Still, it’s the thought that counts, and an indicator of the level of thought and detail exercised by Jones in these shorts.

Carl Stalling comes in clutch with his music scores, to the surprise of nobody. That, and Jones’ continually conscientious directing; the camera follows Porky as he tinkers along, bucket in hand, smile on his face. Airy violin plucks match his equally plucky demeanor—violin plucks that are soon interrupted through a brazen, bold, slightly slurred motif of “The Old Gray Mare” that seeks to accompany the introduction of the horse as he gallumphs into frame. Porky’s violin plucks remain on top as both characters, both demeanors, both attitudes converge. Parallels are striking and significant and feel calculated rather than discombobulated, as there’s certainly a risk of such overlapping music and action to melt into incoherence. That is thankfully not the case.

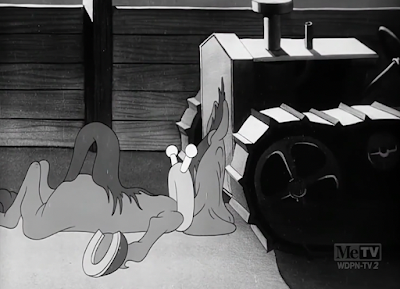

Such parallels also seek to surprise the viewer; both the horse and Porky trot along in separate planes, which is helpful in offering a side by side comparison. Following behind in the same plane would probably seem more organic—ironic, since it’s an arguably more flat means of composition—but organicism isn’t the end goal. Rather, having the horse collide head on with a tractor, is. Sudden and successfully disarming, the appearance of the tractor validates any potential questions as to why the horse seems to be pursuing Porky diagonally rather than in a straight, horizontal line. All in the name of obedience to a gag.

Physics of the collision itself could stand to be a bit more exaggerated, as the horse seems to just flop over in a rather stolid manner. Then again, such straightforwardness encourages its own unique humor and tone by underplaying such a violent blow to the head. Such is politely furthered through the coy, aware grin by the pony to the audience that clearly communicates “I meant to do that”. Exaggeration and wildness and distorted reactions from the horse isn’t the intent, nor is the manner in how he hits the tractor. Just that he hit a tractor, which again enunciates his vulnerabilities and attempts to endear himself to the audience further.

To the early Jones, endearing is synonymous with fumbling and bumbling, as the horse trips into a trough of water almost immediately after. Sounds of the water dribbling out of Porky’s bucket feel a bit too synthetic—ironic, given that the sound seems to be sourced from pouring water into another source of water. It’s a mechanical tinkling that calls a bit too much attention to itself in its attempts to feel and seem realistic—any sort of sloshing sounds would have fit more easily, but is again an incredibly minor nitpick given the grand scheme of the entire sequence.

Realism in water effects does prove to be a focus, however, whether through sound effects or the physics of the water itself. Attentiveness in its physics and effects even extend to how the water interacts with its environments—for example, a trickle twining around the curves of the pipe and sliding down in perspective after the horse trips in. Another symptom of Jones’ studiousness in regards to the Disney philosophy, who were as big—if not moreso—on their effects animation as they were their character acting and believability.

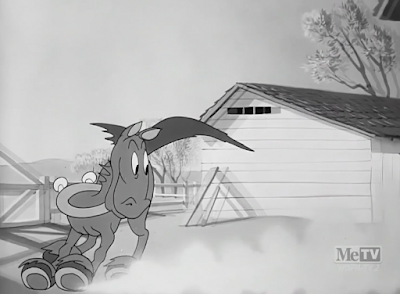

Now, as he traipses back to Porky, the horse can’t even seem to walk right; his hindquarters flail aimlessly in the air as he still manages to propel himself forward. Again—like so many other aspects of the cartoon—it’s an effective way to communicate the horse’s endearing imperfections, and a philosophy of Jones’ cartoons since the very beginning. However, the actual execution becomes cloying after awhile. The audience has well been acquainted with the horse’s mannerisms and quirks. Now, it slips into the territory of registering as visual noise over a guided piece of character acting. His legs flailing in the air don’t feel bound to any sort of weight or kineticism—there’s an aimlessness in the animation that wasn’t exactly intended.

Nevertheless, he demonstrates his potential as a show horse by grabbing the pail of water and offering to carry it in his mouth. Porky seems charmed by the gesture—perhaps there’s a chance after all.

If there was, any and all hopes are quickly dashed as the horse trips over a stake in the ground. Bucket and water go flying…

…and land on the only logical target. Mechanical, tinny water sounds are again somewhat ill fitting, but nevertheless accomplish their mission of bringing attention to the water dousing Porky. Now, he is the prime subject for Jones’ indulgences—cute, tiny character with obtrusive object on their head that makes them seem all the more charming and diminutive. Filmmaking is sympathetic to both parties: Porky isn’t a jerk who refuses to take in a horse, and the horse isn’t a complete and utter nuisance without good intentions.

A particularly toothy grin that seems more akin to the Tex Avery unit’s house style at that time (that is, whoever was currently in possession of Rod Scribner) indicates that the horse has some shred of humility. If not humility, then at least awareness—enough to know that the currently outcome wasn’t exactly desired.

Nevertheless, they both try for their respective round twos: Porky’s round two entails lugging another full pail of water, the horse’s round two being more signs to endear himself to Porky in hopes of adoption. Animation of Porky lugging the water is particularly attentive: glancing at the bucket, giving additional support by holding it from the bottom, and the water sloshing from the sides are all exceedingly convincing in demonstrating how heavy it is. Especially compared to how freely it hung from the horse’s mouth. Perhaps he was more helpful than Porky would like to admit.

Elsewhere, the horse’s own redemption is structured as an exact parallel to his first encounter with Porky. Same surprised take, same camera pan, same proud pose, the only difference lies in the contents of the sign. This time, he boasts his proficiency in steeple chasing.

Paul Julian’s background work remains stellar, even within the limitations of working in monochrome. His eye for tactility and texture is particularly strong through the close-up shot of the steeple and the façade of the barn; differentiation in textures is often a solid, poignant aspect of his work, and here is no exception. Environments feel more lived in and believable as a consequence. Likewise, characters such as Porky and the horse especially juxtapose against such rich, grounded details with their opaque, fleshy softness to great success.

The horse’s preparations for his performance are again ushered into the overriding critique of the short in that too many beats have a tendency to feel belabored or exhausted. His jumps, his gallops, and other wind-ups to convey his ecstatic need to prove himself all look and feel very nice, again united through strong posing and clarity, but the novelty—and attention span of the audience—is quick to wane. If the resolution of the gag was comically abrupt, that could have played to its strength, but such is not the case. There are certainly worse ways to be indulgent, as it again looks good and conveys Jones’ intent; unfortunately, its sense of arbitrariness can’t be shaken entirely.

Additionally, execution of the actual resolution itself—that is, the horse taking off, sailing through the air, and crashing through a barn—boasts a few minor hiccups. As is the case with the above critiques, the main idea is conveyed and is ultimately the most important priority. Animation nevertheless feels somewhat stiff; the horse seems to levitate off of the ramp rather than pushing down and jumping off. Upon entering the barn, his cel rotates in a mechanically noticeable manner to cheat his body through the doorway, almost encouraging the illusion that he can fly (and control it at that) rather than being propelled into the air with no means of direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment