Release Date: July 5th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs), Kent Rogers (Willoughby)

Who ever could have anticipated that such a seemingly benign Bugs Bunny cartoon, doing exactly as the title alludes to, would cause so much turmoil within the Schlesinger studio. Outside of it too, for that matter.

Thanks to the sleuthing of animation historians such as Thad Komorowski, Michael Barrier, Keith Scott and Frank Young, the details of the “situation” have largely solidified. I once again find myself parroting the likes of their wisdom, and have them to thank for putting such rumors and misinformation to rest. Like so many affairs with these cartoons, the truth was largely clouded by myth, confusion, and speculation. Given that Avery himself was (understandably) complicit in contributing to the misinformation, difficulty to discern the truth is understandable.

So, what’s the big deal?It isn’t necessarily the cartoon itself that is objectionable. Rather, the ending. Details about what the ending entails (and the disagreements that ensued) will be focused on towards the end of the review, but the short of it is that 40 feet of film footage was cut from the ending. Avery disagreed with Schlesinger’s decision and argued to keep it in; Schlesinger suspended Avery for four weeks as of July 1st, 1941 (as one newspaper article reporting the dispute on July 2nd mentions the argument occurring “noon yesterday”).

Avery never returned to the studio.

It would be naïve to insinuate that this dispute was the sole reason responsible for his departure. If anything, it gave him an excuse. As Devon Baxter recounts, Avery had tried pitching a series of shorts to Schlesinger where live action footage of animals was dubbed over with voices, courtesy of their animated mouths. Schlesinger—probably rightfully—objected. Thus, finding himself with four weeks of free time, Avery headed to producer Jerry Fairbanks instead.

Such spawned Paramount’s Speaking of Animals shorts: remarkably, the series lasted for nearly a decade, hitting exactly 50 shorts from 1941-1949. Avery’s first cartoon, Down on the Farm, even had the distinction of receiving an Oscar nomination. Clearly the meal ticket to success lies in animating mouths on top of stock footage of animals.

One of animation history’s greatest miracles is that this gig was as temporary as it was for Avery. After making only three shorts, MGM reached out in September of 1941 to ask if Avery wanted a directorial role. It would be here that Avery unequivocally made his best cartoons, utilizing all of the principles he learned under his experience at Warner’s and pumping them full of steroids. He wasn’t as chained to the limitations of recurring characters as he was—and would have continued to be—at Warner Bros. Even Bugs Bunny, the king of the crop, seemed to be just another vessel of comedy for him. A unique vessel, but a vessel nonetheless. Gags were the priority, and MGM offered him a chance to truly embrace his vision and impulses.Despite his departure at the time of the short’s release, a backlog of shorts with his hand involved would continue to extend into March of 1942. Aviation Vacation, All This and Rabbit Stew and The Bug Parade were seemingly completed by Avery himself; The Cagey Canary, Wabbit Twouble, Aloha Hooey and Crazy Cruise were all started by him, and finished up by Bob Clampett.

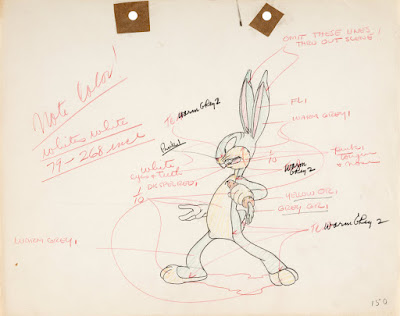

It’s an unfortunate footnote in Warner history, undoubtedly, but one that reaped many more benefits in the end than those lost. Avery’s career and vision blossomed at MGM, able to create both some of his most iconic cartoons and some of the most iconic cartoons to grace the screen. Likewise, as has been repeatedly mentioned in past reviews, Bob Clampett’s acquisition of Avery’s unit was possibly the best development that happened to him at Warner’s. The incident that occurred with the production of this short—that, again, will be covered in more detail at the end of this review—was just another factor in Avery’s decision to start anew rather than the only factor.With that, we settle into the meat and potatoes of the short itself. Willoughby makes his final appearance under the hand of Tex Avery and, for the first time, boasts a different voice. Kent Rogers, continuing to make a name for himself, steps into the role with ease and channels the dim witted earnest that renders the character so endearing. He maintains the same design philosophies boasted in The Crackpot Quail—the only difference being that his color scheme is now a rich brown and gray rather than coffee and tan.Likewise, being paired up with the culmination of his prior two adversaries proves beneficial as well. Both George from Of Fox and Hounds and the eponymous Crackpot Quail are one of many Bugs Bunny clones—synonymous wiseacre voice and cool, collected attitude, a drive to heckle the poor sap for their own entertainment. They are molds of Bugs Bunny, but not the Bugs Bunny. So, what better way to cut to the chase than shunt Willoughby against the very root of his adversaries?

Such moreover marks the third of four instances in which Avery would cavort with his prize creation. Writer Mike Maltese returns not only for his second team-up with Avery, but second-team up with the rabbit as well—both men pivotal in the evolution and development of the rabbit. What Avery established, Maltese would refine, inflate, or even deflect against in later years when collaborating with other directors (ie. Chuck Jones.) This fledgling experience proved integral in investigating what makes the character tick.

Even the opening to the cartoon—not even the title credits, but the Merrie Melodies branding that lead beforehand—would be attached to the character for years to come. For the first time ever, the Warner shield that zooms into the center comes armed with a guest. A lackadaisical, carrot munching guest.

Five (or ten, if wanting to fuss with technicalities) cartoons to his name, and the rabbit already has the privilege of invading the cartoon before it even starts. Perhaps that in itself isn’t even as notable as the fact that he doesn’t seem too pleased about it.

Only briefly does he catch our eye. It’s an incredibly quick maneuver—this opening title is perhaps best remembered under the version animated by Art Davis, where Bugs holds that same contemptuous eye contact with the audience before catering to his affairs, with said eye contact lasting twice as long—as though to indicate he’s already aware of our presence. He doesn’t need to take the time to open his eyes and study the rude awakening that is hundreds of eyes peering at him all at once. In this early opening, he just seems to know. He always seems to know.

Thus, with his privacy thoroughly invaded, he reaches off screen to pull down the Merrie Melodies title card like a curtain.

Not only is the metaphysical humor and awareness a great novelty, but the maneuver is an incredibly telling piece of business on Bugs’ part. Particularly Avery’s Bugs, who, as we have seen in cartoons such as Tortoise Beats Hare, possessed a wily, if not confrontational spirit. He could get mad. He could get aggravated. He had his moments of vulnerability and thin skin. Avery’s Bugs clung onto the vestiges of that zaniness established through Ben Hardaway’s Bugs, as studied in our analysis of A Wild Hare. He’s far from the cavorting, hayseed nuisance (thank goodness!) he once started off as, but perhaps was just as far from the suave, unflappable, wholly in-control trickster the world has come to revere and love.

That Bugs interacts with the opening titles isn’t exactly radical in itself; many a titular cartoon character preceded their cartoons: Woody Woodpecker destroys his own title card before succumbing to a deranged fit of laughter. Popeye would materialize from one of the Paramount logo’s stars and blow his pipe. Albeit a still image, the Looney Tunes title card for the 1941-1942 season has Porky lounging on top of a fence painted with the series iconic lettering.

Rather, it’s the sheer disdain in Bugs’ face that sets him apart from his cohorts. Popeye smiles. Porky smiles. Woody smiles, if not completely all there in Emery Hawkins’ gorgeous animation of the opening, capitalizing on his lunacy the most efficiently. All of these happy-go-lucky cartoon stars are happy to immerse you into their world, to allow a personal glimpse at their everyday lives and happenings.

Not Bugs. To him, you’re a nuisance and a waste of his valuable time that could have been better spent eating carrots and luxuriating. Nevertheless, an obligation is an obligation. He’ll treat you to a cartoon, seeing as he has no other choice, but he will make a point to remind you that you’re low on his list of priorities (which, surely, are miles and miles long.)This same philosophy extends even to the cartoon’s actual title credits. One of a handful of photographed titles that would—and has before; Porky’s Garden, keeping it local to Avery, likewise featured photographed titles rather than a painting—precede these cartoons, the decidedly rabbit shaped shadow that looms over the lettering is just as conspicuous as the lettering itself.

That, too, is the point. Bugs’ presence is intended to feel obtrusive, interruptive, immediately commanding authority and attention. His heckling isn’t reserved just for Willoughby, but for the theatergoer as well. Blocking our view of registering the short’s name right away is just as much a form of heckling than anything else he does in the cartoon. Likewise, the titles being photographed encourages its own personal dissonance, as it makes Bugs seem even more realistic and alive. His painted shadow overtop a painted background is one thing, ruminating in the same medium. A painted shadow overtop a prop, photographed background, insinuating that Bugs is actually interacting with these realistic environments, is another.

He doesn’t even get out of the way for the sake of seeing which names were responsible for the creation of this cartoon. Moreover, his hands are on his hips, posture erect—this in itself is an intimidating, imposing gesture that once again commands authority and attention. It’s one of confrontation. Holding a half eaten carrot in his hand would be different, as it would imply he stumbled upon these enigmatic words and was stopping to take a gander while tending to other leisurely affairs. Not here. His presence is by no accidental. All of his attention is cast onto discerning these troublesome titles and why they’re invading his precious forestlands. Casting his shadow at a diagonal angle likewise induces unease through dynamism—diagonal angles insinuate movement and action, which again furthers Bugs’ case as a living, breathing, combative being.In any case, the short opens to much less confrontational matters. Enter Willoughby. He dutifully engages in a reprise of his “hunting dog walk” from The Crackpot Quail; his musical accompaniment boasts an abrasive, peppy swing to it, as opposed to the more contemplative and youthful music strains in Quail’s instance. Heckling Hare, as breathlessly expounded upon in the introduction, is an abrasive, peppy cartoon.

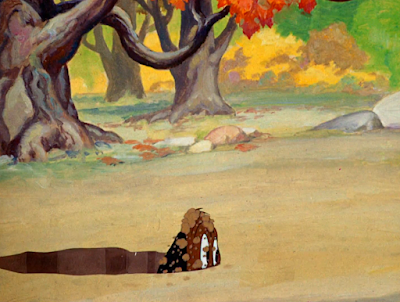

A deep hole doesn’t stir Willoughby’s unbent concentration. If anything, it seeks to accentuate the polite asininity of his walk—his sniffing grows more furious in a vacuum, the tinny echo accentuating the ferocity of his handiwork. Virgil Ross is the animator behind the walk, finally having been perfected after three cartoons.

Realization hits—no matter how delayed it may be. Rather than engaging in a wild, distorted take, Willoughby merely freezes in his tracks, peering off screen. No settle, no overshoot, no antic. Even Bugs doing that same “freeze take” in Tortoise Beats Hare was more noticeable; the suddenness in which Willoughby comes to a halt is, in a way, more shocking than any sort of wild expression of bewilderment, as the audience can’t even be sure of what they just saw. It blends so seamlessly into the action, creating a disconnect that the audience is momentarily left second guessing themselves. Stalling’s orchestrations coming to an equally heavy pause serve as the biggest aid in ensuring this isn’t accidental.

“Duh—a rabbit hole!”

Kent Rogers injects a brand of dopiness in the dog’s voice that differs from the nuances of Avery’s deliveries, but maintains that overall belabored innocence. Avery’s Willoughby was more huffy, gallumphing, rich in his vocal tones that even communicates a warmness—helpful in endearing the character to the audience. Rogers’ Willoughby follows those same principles, but conducts itself with a more nasal, exaggerated drawl. Both voices honor the character and his needs, just choose different facets to accentuate and embrace.

Up until this point, Willoughby has largely conducted himself with an overwhelming innocence. Crackpot Quail had its moments where it was demonstrated that Willoughby could be pushed over the edge, could be capable of feeling drive and rage and humility, but those feelings were either the climax to a crescendo (for example, realizing the quail was baiting him).

Here, it’s disarming to see him carry such a duplicitous expression right from the start. With surprising deftness, he tinkers over to the rabbit hole, a mischievous grimace on his face as he teeters along to Stalling’s playful accompaniment of “The Umbrella Man”. The maneuver is intended to be funny and absurd over scary or tense—and it certainly is—but nevertheless comes as a surprise. Such hostility indicates an awareness, a recognizable need to be hostility. Avery and Maltese waste no time getting down to the introduction of the character the audience truly cares about.

Thus, the character the audience truly cares about appears. Ross’ animation extends to a gorgeous close-up of Bugs(‘ ears) feeling up the predator that lies outside the safety of his rabbit hole.

In a way, the routine is a twisted, exaggerated glorification of Bob McKimson’s animation of Bugs feeling up a carrot in A Wild Hare. Both instances boast wonderfully tactile, dimensional animation; the sensation of Bugs’ ears brushing against and curling around Willoughby’s mangled teeth—which solidifies his role as a predator, making him seem uglier and more menacing, if only for that moment—transcends the screen and can absolutely be felt.

Likewise, Bugs’ ear warning the other demonstrates growing versatility of the character, finding more ways to distort and exaggerate him. Obviously, this priority would lessen over the years, as Bugs wasn’t a character who demanded large, emotional distortions. Avery nevertheless embraced such caricature; Bugs was another vessel to him. A vessel to maintain and flaunt takes, reactions, funny lines. All This and Rabbit Stew would feature even more distortions and wild takes on the character; getting inside his head and carving out the intricacies wasn’t so much a priority as discovering how he could make him more bombastic and entertaining.

Regarding takes, Willoughby initiates an old favorite: the classic Avery head spin. Dry brushing adds a sophistication to the take, simulating a motion blur that renders such an unnatural gesture more believable and urgent. That the take is so quick, regarded as an afterthought rather than a full frontal focus, is helpful in streamlining its delivery.

Whereas the Willoughby of yore may have greeted the audience with pitiful, innocent, befuddled blinks, trying his hardest to ponder why his treat would run away from him, the Heckling Hare Willoughby is a servant to his one-track mind. Getting the rabbit takes absolute precedence. Thus, with comparatively disarming intensity, he heads right for the source.

The source that resides in an adjacent rabbit hole and observes from afar. Avery—funneled through the vision of Bob McKimson, whose Bugs is incontestably gorgeous, controlled—establishes a deliberate parallel to the opening of A Wild Hare, potentially implying the beginnings of a formula. Bugs’ ears feeling up Willoughby’s teeth is an answer to Bugs feeling up the carrot. Willoughby digging in the hole is a parallel to Elmer digging in the hole. Both scenes result in Bugs ascending from a conveniently adjacent burrow with a spinning flourish, contentedly observing his adversary at work. Already, in just a little under a year, the artistic growth (regarding both Bugs and the art direction as a whole) is palpable.

Grabbing his ears, Bugs heaves himself out of the whole and marches over to Willoughby, carrot crunching a go. In spite of this scene serving as a direct parallel to a synonymous instance in Hare, it is executed with a certain level of control.

As mentioned in the introduction, Bugs still clings to some vestiges of his screwball roots—pulling himself out by his ears is screwy. Feeling Willoughby’s teeth with his ears is screwy. He’s still got those fledgling screwballisms in the recesses of his being, but it’s a different class of exaggeration and zaniness than seen even in A Wild Hare. Comparing the two scenes back to back, Bugs can hardly contain his excitement in Hare. Here, he demonstrates brief glee at the prospect of having someone to heckle, but is quick to put on a nonchalant, calm cover.

So much so that his carrot chewing and polite observation of Willoughby’s digging extends any actual confrontation. Avery instills a solid incongruity between the alarm of Stalling’s musical arrangements and Bugs’ blatant disregard; the camera may be focused on Bugs, but the hurried anxiety of the music takes pity to Willoughby. For him, this is a life or death situation—he has to have that rabbit. Never mind what happens if he didn’t get him. That’s not the point, nor is it on his mind. He must have that rabbit at all costs. Bugs, meanwhile, revels in Willoughby making a stooge of himself. No shred of concern clouds his vision.

“Um,” he bothers to ponder between bites of beta carotene, crescendoing to that ever revered utterance: “What’s up, doc?”

“Dahah, dah—dere’s a rabbit down here, and I’m going to catch ‘im.” Rogers’ deliveries make it sound as though Willoughby can barely wrap his tongue around the words, he’s in such a breathless flurry. Likewise, wasting time speaking to this spectator detracts from his mission of maintaining a one-track pursuit. Too much outside stimuli. (Never mind that he’s technically the invasive one, even maintained through the way he juts his nose under Bugs’ chin.)

Sustaining his indifference, Bugs bothers to munch on his carrot for just a few moments more. Every time he takes a bite of the vegetable, he casts his eye direction on it. A carrot—of which he goes through many in a day, a fixture of his everyday routine, constantly joined at his hip—is much more deserving of his attention and time than this hilariously dopey dog. It’s such a menial gesture in the grand scheme of things, but is just as imperative in furthering his conceit like everything else.

“Welp,” he concedes, his patience with this novelty clearly expired, “I’ll be seein’ ya.” The meticulousness and beauty of Bob McKimson’s animation—its dimension, its believability, its specificity—can never be overstated. “Good luck, doc.”

A viewer today almost wants to argue that the time between Bugs’ departure and the eventual sting of realization from Willoughby is too far apart. Perhaps in other circumstances, but the elongated length here is perfectly suited for the contextual needs of the cartoon. Willoughby isn’t a character who operates at furious speeds as a default. Stretching out that frantic digging cycle just a few beats longer allows the sudden shock he receives to be that more potent. Everything seems to come to a screeching halt: the dirt, the music.

McKimson incorporates exclamation marks on the dog as he grapples with the reality of the situation, which is a drawing choice that seems amusingly retroactive. It’s a holdover of traditional cartooning, newspaper cartooning—a shorthand and expression much more at home in terms of practicality on a piece of paper than in the animated medium. Not to say these little marks are bad because they’re impractical; quite the opposite, in that they add flavor and flair, a novelty. There just comes an amusing dissonance of sorts, seeing such tight, modern art direction against a homage of sorts to a prior era.

Having thoroughly identified “da ra-bbit,” Willoughby makes a break for it. Cyclical limbs and the ferocity in which he launches himself are yet again reworked from the foundation set by The Crackpot Quail. What was the result of minutes of build-up in the former seems to explode almost instantaneously here; Willoughby serves more as a means to an end, a way to get the plot moving, whereas Bugs is the character Avery wants to ruminate in. The inverse was true for the previous two Willoughby cartoons.

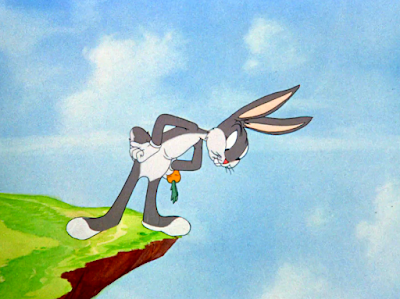

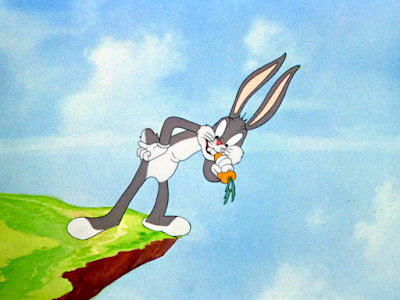

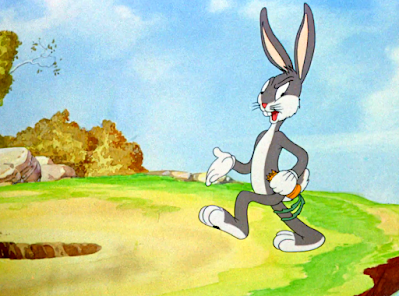

Cutting to Bugs strutting along without a care in the world seems sudden in its execution, but that, too, is a product of purpose. Head back, legs swinging, a bounce in his step, carrot haughtily lodged in his mouth like a cigar as he struts to a demure orchestration of “The Fountain in the Park” is intended to serve as a parallel in every single way to the ferocity of Willoughby. He knows he’s got his target riled up, and that refusing to entertain him in a chase will only get him wound up more. His philosophy of dealing with Willoughby is closer to George’s in Of Fox and Hounds than The Crackpot Quail, who did entertain the dog’s fantasies.

Not Bugs. At least, not in this moment. Part of his nonchalance does seem to be a genuine desire to get his goat further—another is that he sincerely doesn’t seem bothered. Willoughby is not a threat… in spite of being his most threatening yet.

As if to accentuate all of the above points, Bugs dips into his rabbit hole as Willoughby charges ahead. The animation of the maneuver is somewhat stilted; in different circumstances, there would have been more steps to ensure it looks as though he’s properly engaging with his environments. Regardless, the suddenness of the drop is once again intended to be jarring, sudden, all too convenient. That he almost magically seems to get sucked into this vortex that he declares home is a joke in itself. Especially knowing that this is a Bob McKimson scene, who clearly knew how to depict a character going in and out of a hole.

In another instance, Willoughby rushing off screen would have been accompanied by an ear splitting series of crashes and bangs. Falling off the never ending cliff in Of Fox and Hounds. The constant barrage of trees that awaited his every move in The Crackpot Quail. No such luck here, as that attracts attention and sympathy to him. Not that he’s undeserving of such pathos and focus, but, rather, Bugs’ reactions and interworkings are a bigger priority.

So, instead, Willoughby corrects course by spinning to a gradual stop in front of the hole. The gesture is ridiculous and proudly mechanic to exacerbate Willoughby’s role. Willoughby is funny. A funny character moves in funny ways. A funny character moving in funny ways purely by accident is the funniest of all.

Confronting the rabbit hole allots room for Rod Scribner’s animation: some of his most impressive and telltale yet. The distortions, the wrinkles, the gummy teeth, the freneticism—all of these aspects would be reigned into and exaggerated even further under Bob Clampett’s direction. All of these trademarks of his work have been seen in many a cartoon before—even in his brief stint under the direction of Chuck Jones. Yet, the sheer control, the length of the sequence and the confidence in which the routine is executed sets it apart from prior examples. His animation for Avery has always had that trademark manic twinge to it, but this could potentially be the first scene that is 100%, unequivocally identifiable as his the second the audience lays eyes on it. (Ignoring that theatrical audiences in 1941 had no idea who Rod Scribner was, and probably never would.)

Here, Bugs and Willoughby engage in one of the oldest tricks of the book: the mirror routine. Popularized by the iconoclast that is Duck Soup, the routine extends beyond even that movie—likewise, this certainly wasn’t the first time it had been adapted in a cartoon. Nor would it be the last.

Perhaps what makes it so impressive and captivating isn’t even the mania of the drawings—which certainly is a factor—or the amusing ways in which Bugs leads Willoughby to imitate him, but the way in which the routine is completely shattered. So many other employments of this trope only stop when they have to: a character gets wise to the antics of its “reflection” and confrontation ensues, spurring further wacky antics and hilarity.

That Bugs stops the charade by his own volition is a staggering feat within itself. It indicates a certain level of trust—trust that Willoughby will continue to convulse and gesticulate and make a royal fool of himself, trust that Willoughby won’t notice, and trust that he himself is in a safe enough position to even do so. Even characters in the same routine that didn’t involve a life or death chase were reluctant to stop, lest they blow their cover. Bugs, once again, is different.The disassembly of the routine isn’t entirely spontaneous. Bugs, ever slowly, begins to distance himself from the rhythm. The gesticulations are still synonymous, but Bugs eventually pushes just a little further, prompting Willoughby to lag. More and more, he eases himself into that irregularity that soon justifies him dipping out entirely. Such aids in the success of his intent of dropping out—it’s a risk, but he’s still not stupid enough to just stop directly. Easing his way out and messing with Willoughby’s rhythm is how he could be sure that he could untangle himself from the convulsive rhythm consequence-free.

Most impressive of all is that Bugs has the guts to mock Willoughby to his face. Reveling in the dog’s frenetic distortions, he takes his sweet time in unearthing a sign that he just seemed to have on hand. The sign that reads “SILLY ISN’T HE?” in big, bold letters is just as much a commentary from Avery as it is Bugs—if anything, it’s almost as though Bugs is delivering Avery’s message. Perhaps that stems from the understanding that Avery loved his corny sign gags, and would wholeheartedly embrace his obsession of “[adjective], isn’t it?” during his MGM years.

Yet, this instance is different. What makes it funny to viewers today who have maybe become spoiled by this once novel gag is how calm and collected the delivery is. A tone of condescension seems to prevail over the oftentimes purposefully hokey, cornpone nature of synonymous sign gags. It seeks to ridicule just as much as it seeks to entertain. Especially given Bugs’ unwavering, cool eye contact with the audience. The joke isn’t presented at them, but with them, to them—they’re in on the joke, just like Bugs.

Appeal and sharp timing in Scribner’s drawings are yet another imperative aspect to the scene’s success. Willoughby rapidly switched between gestures, eventually losing all antics, follow throughs, settles, any animation principles that intend to cushion a blow and induce a more organic sense of timing. There is nothing organic about this scene. That’s the whole point. The ferocity in which he switches from pose to pose (and the asininity of the poses to begin with) believably captures the sensation of being stuck in an uncontrollable loop. It wouldn’t be nearly as funny or entertaining if the audience got the impression that Willoughby was in control of his actions; Scribner, ever the expert on manic animation, does a powerful job of conveying such histrionics.

Of course, Bugs isn’t a complete masochist. He realizes when enough is enough—even if it’s just a few moments too late, giving him extra time to revel in his handiwork.

Rising out of his hole on a platform is a leftover from his earliest days as a cavorting, omnipresent, magician adjacent rabbit. It’s absurd, it’s out of place—that, paired with the stinging nonchalance of his demeanor, makes for an especially effective combination. These sorts of screwball entrances and exits would occasionally weasel their way into his cartoons as the ‘40s stretched on, a subtle homage to his roots. McKimson’s Acrobatty Bunny, for example, features an extension of this convenient platform/hole amalgamation.

Of course, narrative priorities do not rely on how Bugs gets from point A to point B. The large, imposing baseball bat he wields in his hands attracts much more attention.

Avery’s shorthand for the collision is nothing sort of genius. Instead of actually depicting the bat making contact with Willoughby, the audience is instead treated to the antics of Bugs winding up and then the aftermath: a disarmed Willoughby, a bemused Bugs, and a broken bat. Separating the two separate ideas are a mere pair of color cards. Simulating these flashes of pain is much more startling than watching Willoughby get hit—the audience expects to be spoon-fed the information, so when the shortcut occurs, they’re left just as blind-sighted. Almost as though Bugs cracked the bat over our skulls in the crossfire.

Moreover, Avery seemed to understand that it’s not exactly a pleasant circumstance. Willoughby may be the antagonist of this cartoon, but he’s still—and will forever be—Willoughby. We pity him. We laugh with him. Just because we also root for Bugs and want to spy on his antics doesn’t mean we can’t put our stakes in Willoughby as well. Thus, in an oxymoronic way, the arguably more painful route of allowing the viewer to paint their own personalized depiction of the blow is, in a way, also more forgiving. We just see the means to an end. We know that Willoughby got hit. We aren’t subject to any unpleasant facial expressions or skull crushings that may arouse more sympathy and pity than entertainment. Avery straddles a very fine line with surprising ease.

Bugs pecks Willoughby on the nose as consolation. Scribner’s distortions continue to amuse—just as much as the rapidity in which Bugs makes a spinning, flourishing exit, understanding that Willoughby is free from his curse and now is the time to run. Once again (if only on a subconscious level) the prototypal Bugs of yore seems to be called upon in the enigmatic manner in which he departs, practically disappearing into nothingness. What’s so different about his exit here than a similar vanishing exit in Prest-O Change-O, where he summons himself out of existence? Sophistication, intent, context, execution, yes, but on the bare, surface level, those connections and roots are still there.

Rev Chaney is next to receive the animated baton, depicting a fleeting moment of vulnerability as Bugs nearly topples into a pond. By pulling out a swim cap, he’s obviously not afraid to accommodate this change in terrain, but having to take a moment to catch himself indicates a lack of invincibility. He either overestimated the ferocity of his exit, didn’t realize the pond was there, or didn’t think to expect it.

Either way, such a seemingly inconsequential tangent grounds him to the story. It’s no fun if Bugs is completely invulnerable and invincible. A little check of the ego now and then reminds the audience that this is a double sided chase—what fun is there to be had if the audience knows right from the start that Willoughby is going to lose? That in itself further justifies his aggression touted at the top of the short: survival of the fittest. Willoughby has to be more aggressive to be a worthy opponent against Bugs. Otherwise, the audience just feels bad for him—and not out of endearment.

So, amidst a life or death situation, perhaps no solution is more Bugs Bunny-esque than to take the time in placing a swim cap over his ears. Bob McKimson perfectly captures the meticulous, conceited fussiness of such a gesture—Stalling’s frantic music score reminds the audience that this is an urgent situation, and Bugs would be better off spending his time making an escape. That he wastes such time in attending to such menial matters isn’t only a sheer display of confidence: perhaps it’s even a sheer display of stupidity. (Much more the latter.)

Bugs even nudges the sides of his head, as though tucking stray hairs and ensuring everything fits. Great attention to detail that really embraces the capriciousness of the whole affair.

In fact, it was so effective that the animation is somewhat clumsily retraced in Bob Clampett’s Tortoise Wins by a Hare—tracing over the animation prompts it to lose some of the tension and weight in the elasticity, Bugs’ fingers losing their form beneath the cap. That in itself serves as a testament to the success of the original scene here.

Bugs is now free to swan dive to his heart’s content.

Willoughby, too, for that matter. His jump doesn’t follow as clean nor concise of an arc as Bugs’, but that in itself proves helpful in furthering the outcome: landing right on his head. The reverberations that shake his body after contact are serviceable—certainly more humble than other similar resolutions and takes in prior Avery shorts, but there isn’t a need for extravagance. Especially when Bugs so meticulously established himself as the extravagant foil. Willoughby’s collision is meant to be as inelegant as humanly possible, and it certainly is.

Through a split-screen shot, Avery reveals that the collision isn’t entirely out of Willoughby’s own ineptitude, but that the forces of nature are against him instead. Bugs proudly occupies the decidedly vacant, cavernous pond waters in which Willoughby observes from the sanctity of his unnaturally steep cliff. Even background artist Johnny Johnsen is able to contribute to the power imbalance: notice how clear and vibrant Bugs’ half is, sunlight pooling in and even having a rock to conveniently lean against in amiable smugness. Now, take a look at the tin can lodged against the bottom of the cliff—Willoughby gets the side with the sharp rocks and garbage.

Additional kudos extend to the ink and paint department. Avery employs a tactic seen even in his ‘30s cartoons, in that any blacks or deep, dark colors are washed out through lighter palettes to convey depth and dimension. Especially by having half of Willoughby submerged and half dry, the viewer is able to assess and embrace the visual juxtaposition. The sensation of the characters and environments being submerged is strengthened all the more.

Alleviating further hot air from the chase—as well as strain on the animators and inkers—Avery conveys much of the pond chase underwater. It eases visual monotony and clichés, enables the audience to remain engaged by piecing the unseen action, and offers new room for gags and nonsensicalities that may have been hindered through repetitious cycles.

A somewhat extended vignette of Bugs and Willoughby swimming through the water, their presence indicated only by bubbles, is (of course) accompanied by a literal orchestration of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles”. A pedestrian but endearing gag, whose likability partially stems from its intrusiveness. Dedicating this much of a focus to such a nothing of a gag is amusing in itself. A very Avery thing to do. Likewise, Willoughby’s bubbles are depicted through a much more imposing arrangement of the same song down an octave, communicating tone and intent from that alone.

Bubbles are not only an indication of character blocking, but a representation of emotion. A rock forms a break in the water that allows both characters to snake around it—inevitable confrontation thereby strikes. Depicting this held sting of realization, both characters are conveyed through one bubble each that remains suspended in the water, a tense music sting matching the held suspense. Avery gets a lot of mileage out of this little water routine—his career at MGM would find even more ways to warp and twist similar premises.

Thus, the chase persists. Both characters are now portrayed through their various bodily extrusions.

Animator Rev Chaney returns to animate the log sequence; Bugs engages in an age old impracticality…

…whereas Willoughby’s own methods are impractical, too, but for different reasons. Contortions on his tail serve a clever indicator of his emotions and drive. Brevity on the reverberations of his and the log are duly noted; we just had a gag of Willoughby reverberating after hitting his head off of something not too long ago. Understanding the parallel, Avery shortens the amount of time here, trusting that the audience has gotten the point.

He nevertheless makes a swift recovery.

Avery seems to follow a theme regarding his directing, in that there are cuts that fleetingly seem just a bit too sudden. More likely than not, this is a carefully calculated maneuver to be entirely purposeful. The audience is meant to be disarmed by the suddenness in which Bugs appears lounging on Willoughby’s sopping back. What better way to sell that jolt than having him seemingly materialize on his back in a matter of seconds? Hook ups between the two scenes aren’t staunchly abided by, but Avery has no reason to do so.

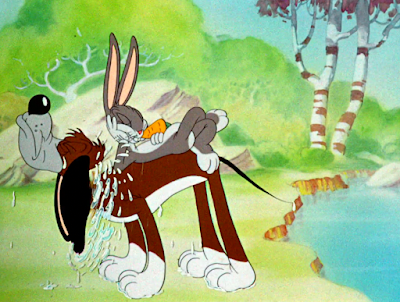

Bob McKimson handles this sudden subversion. His continuously sculpted animation paired with powerfully tactile water animation from the effects animator create a powerfully tangible result.

Especially when the aforementioned sculpted animation is accompanied by such equally believable character acting. Once again, Bugs is briefly served a dose of humble pie as it’s clear he didn’t have Willoughby shaking himself off on his cards. His eyes widen as Willoughby indulges in an antic, quick to cling onto his coat as the dog shakes himself dry to a degree of borderline violence. Shrill sound effects from Treg Brown play an essential role in embracing its intensity.

Both nevertheless make their respective recoveries. Upholding the theme of momentary vulnerabilities with Bugs, he has to face the harsh indignity of taking the time to stop, think, and mull over the next course of action. Not even “how do I stop him from chasing me”, but the much more primally indulgent desire of “Um… lessee… what can I do to ‘dis guy now?”

That in itself is a rarity to us viewers so accustomed to Bugs and his instantaneous ideas. Like his near spill into the water or sudden surprise at Willoughby drying himself, it too is another conveyance from Avery in demonstrating that Bugs isn’t completely superhuman. He’s incredibly enigmatic, and like nothing nobody had ever seen beforehand, but he has his moments of downtime, of befuddlement, of deep thinking, of disarm. The audience is more engaged when understanding that Bugs’ heckling isn’t a matter of sheer perfection. Such lapses give him character.

His solution: tease Willoughby by appeasing his most basic desires. Scratching a sweet spot doesn’t necessarily seem like a productive means of heckling, but Willoughby sure doesn’t seem to mind. McKimson once again successfully captured the reflexive nature of him leaning into the scratch, pawing at his hindquarters and clearly luxuriating in the relief. His giant, gnarled teeth remind the audience that he’s the antagonist of this picture rather than the sympathetic innocent darling of yore.

Another smoocher from Bugs to assault Willoughby’s masculinity. The intended offense of the gesture seems more effective on a dweeb like Elmer Fudd more than Willoughby, who probably doesn’t even know what masculinity is (nor what it means to have it assaulted), but even this early on, the kiss of death is a Bugs Bunny trademark.

Heart lip smack effects are particularly inventive, especially in a rosy pink.

Avery and Maltese maintain a coherent flow of action by alluding to prior vignettes and actions; Bugs using the dog’s tail as a springboard isn’t only a novel maneuver of getting him off screen, but a parallel to the previous scenes of him and Willoughby diving into the pond…the latter evolving from diver to diving board.

Seeking refuge in the hollow of a tree ensures that Willoughby can’t fit inside, which is exactly why Bugs chooses it as a target.

Not even. Avery maintains his pattern of keeping the audience on their toes as the camera pans over to reveal Bugs lounging on the ground, observing as Willoughby paws and gropes at the open air through the double sided tree.

In a way, such bridges the audience closer to Willoughby—they, like him, expect Bugs to be inside the seemingly one-way tree. Revealing that such is not the case comes as much of a surprise to us as it (eventually) will come to him. Thus, even if it isn’t an explicit focus, there remains a subliminal sympathy for Willoughby through all of this. Bugs’ doesn’t entirely have the audience in his consideration. We’re just as much subject to his trickery and subversive ness as everyone else. That’s what makes it fun.

Enter Rod Scribner’s second tour de force of the picture. His acting and knack for distortion may be comparatively subtle compared to the mirror scene (granted, everything seems subtle in comparison), but that continuously mischievous spirit remains. There’s a palpably twisted glee to Bugs as he teases his adversary, observing in insubduable rapture as his pokes of Willoughby’s paw prompts him to reflexively writhe and grasp. Scribner’s own knack for full construction and tactility is certainly helpful in aiding the believability of Bugs’ pokes.

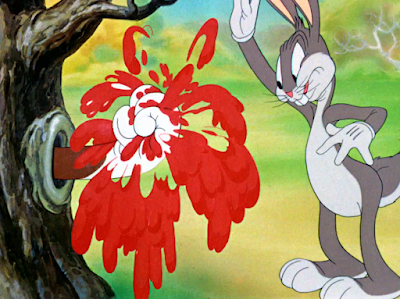

Thus, what starts off as a slightly off beat and disarmingly domestic means of heckling quickly devolves into unadulterated sadism. That’s why Bugs was so gleeful; he was gauging the chances of completely messing with Willoughby’s psyche. As in, orchestrating a completely traumatic event by means of a (oddly pumpkin adjacent) tomato. Squashed tomato = squashed bunny rabbit. Squashed bunny rabbit = murder.

Fullness in the effects animation of the tomato spewing and dripping everywhere justifies the forthcoming psychological turmoil completely. This isn’t a tomato getting squished with its pale, semi-translucent puss peppered with seeds and goo. This is a cherry red murder scene.

Drawing out Willoughby’s reactions enables the broiling histrionics to hit harder in comparison. Now, Avery channels that pathos and sympathy for the character embraced so wholeheartedly in Of Fox and Hounds and even The Crackpot Quail. We aren’t thinking of Bugs. Bugs is irrelevant. Bugs is tomato pulp. Instead, we study Willoughby’s wide, pitiful blinks, the creeping slowness in which he draws his hand out of the knothole, the dread as he ever so slowly uncurls the drenched, dripping crime scene in his palm.

“I… I crushed him,” leans wholeheartedly into his most bare essentials: being a reflection and caricature of Lennie Small. Especially given the relation between Lennie and his own rabbits.

His sobbing histrionics that shortly follow are comparable to synonymous outbursts in A Wild Hare. Like Elmer, Willoughby too proves that he has a desire to hunt Bugs for sport… and when the desired outcome occurs, he’s left distraught and destroyed. Likewise, Kent Rogers’ vocal performance is comparable to Arthur Q. Bryan’s: both are so over the top that the compulsion to laugh and thrill at their vocal artistry overrides the sting of any painful sympathy.

Indeed, viewing this scene alone is enough of an argument as to what a prodigy Kent Rogers was. Wails and sobs evolve into shrill shrieks that sound pubescent in their cracks and pitchiness—it’s loud, it’s disingenuous, it’s telling, and, most importantly of all, it’s absolutely hilarious. Avery concocts a tone that is tongue in cheek, somewhat insincere through the grandiosity of the production, but is still—somehow, someway, pitiable by the audience. Avery nailed the oxymoronic narrative in A Wild Hare, and he certainly nails it here, too.

A fade out and in to the next scene evokes a heavy permanence. Not only does it aid in conveying that an indiscernible amount of time has elapsed—helpful for the needs of the gag—but it’s a transition that instills a jolt, a deliberate breach of momentum. In this instance, there’s a solemnity to it, much more than there would be through a mere dissolve or jump cut.

“Uh-flow-wurs,” snivels Willoughby. Even in mourning, he retains the endearing habit of spoon-feeding the audience easily digestible information they’ve likely processed before him. Twisted as the circumstances may be, there’s a strong charm to Willoughby’s gesture of leaving flowers for the “poor lit-tle bun-ny”; the audience feels just as remorseful for him as he does for Bugs. Rogers’ breathless, wet sniffles are startlingly authentic.

Especially given that the flowers themselves are wrapped: it’s unlikely Willoughby did that himself, implying he event went through the trouble of buying them. A much stronger production value lies in a wrapped bouquet of flowers over some stray daisies he picked along his way. Likewise with the awareness that stems from leaving them at Bugs’ hole as if it were a grave—the bunny lived in that hole, which must mean the bunny likes that hole, so what better way to honor his memory than leave the memento there.

“For me, doc?”

As Bugs—dedicatedly alive, head unsquashed—takes custody of the flowers, a brief animation error can be noted in that the flowers momentarily lose their middles. It certainly isn’t noticeable enough to cause a frenzy; especially not to Willoughby, who has more pressing matters to comprehend.

So much so that he doesn’t even seem enraged as Bugs plants a final smoocher on his muzzle. Mild inconvenience prevails, if anything.

That, too, is temporary. Finally registering that yes, he should be mad, Willoughby engages in a reprise of his earlier hole digging routine. Bob McKimson’s digging cycle is reused once again to drive the parallel home; given that the camera is occupied with trucking out, the repurposing of the animation is disguised.

Suddenly revealing a cliff towering thousands of feet in the air is a bit of a stretch: the foliage that surrounded Bugs’ hole in the opening is conveniently absent. Likewise, Willoughby enters from screen right at the very beginning—an implausible feat if there is no screen right to enter from. That, too, is one of Avery’s strengths; the lack of consistency was obviously noted, and, instead of finding a way to wrangle with it, Avery embraced the disconnect with confidence. It doesn’t make sense. No it does not. Moving on. It’s an admirable attitude for an artist to have—that confidence thusly seeps into their work.

Doesn’t Avery know it. Confidence at this upcoming sequence is what spurred the contentious suspension.

Depicting the towns and fields and farms below the cliff exaggerates its height much more than if there were no horizon line of any kind at all. Seeing what the bottom looks like, the viewer has a frame of reference: that fall is really, really high.

Thankfully, cartoon logic takes pity on Willoughby… if only for now. He remains suspended in mid-air, enough time allotted for him to engage in a petrified take before scrambling back to safety. A ring of dirt around the hole remind both him and the viewer that this was his own doing.

A point of view shot justifies Willoughby’s concern. Johnsen’s lush rendering skills are an invaluable asset—he was able to harness the sort of realism and believability Avery craved. A realism that begged to be contradicted through wild, improbable antics of the characters on screen, concocting a powerful antithesis in itself. Likewise, particularly tense moments (or other special occasions that require such meticulous attention to detail) are made more believable, such as here. Avery’s attention to detail even allots that a very, very, very light overlay pass over the ground beneath the edges of the hole. It’s difficult to discern, but that little milky overlay simulating clouds accentuates the staggering heights all the more. Ditto for Stalling’s discordant, ethereal music score. Something is clearly not right.

“Uh-buh-duh--gee-uh, eh-jeeah... did you see what nearly happened tuh me?” Virgil Ross returns to depict this brief, not so down to earth dialogue scene. Willoughby making a point to mention “me” immediately renders the statement personal. Not “Did you see what nearly happened?” Mentioning himself includes a special stake to the situation, invoking a pathos through such personal connections. Now, Willoughby’s gradually settled into the eye of the public. Bugs was more of a liability in the first half of the cartoon—the second half seeks to entertain and endear Willoughby.

“Yuh, I guh... I gotta be more careful...” Again, the art behind Rogers’ deliveries can’t be overstated. He injects a stronger specificity and range in his impression of the character than Avery, whose own deliveries were still incredibly endearing, but not intended to be sustainable. He spoke in quips, fragments, the longest sentences channeling Lon Chaney Jr. in Of Fox and Hounds especially. Here, Rogers turns Willoughby into his own, independent character in conjunction with Avery’s direction and Maltese’s writing.

With this resolution of safety and carefulness firmly established, Willoughby honors it by falling off the cliff.

It’s telling we don’t hear him scream or make a reaction of any kind. That isn’t the priority. As soon as he exits the screen, he’s irrelevant to Avery’s needs. The entrance of a wily, masochist rabbit takes precedence. Note the lack of any toes.

A bite of a carrot takes precedence over any sort of take or eulogy. Bugs’ feelings—or lack thereof—are clear.

“Too bad… ahh, but da joik had it comin’ to ‘im,” declares the joik out of the duo. “He shoulda watched his step!”

Once more, Bugs is rewarded for his ego. It’s a rewarding aspect of Avery’s cartoons—Bugs can be brash and insensitive whenever the mood strikes, but he almost always receives a dose of his own medicine. It isn’t entirely antagonistic against him, either, but a reminder that he shouldn’t get too high in his britches.

For example, Bob Clampett’s Bugs followed a similar mold of Avery’s Bugs. There were separate nuances, but he retained a wily, abrasive attitude that can sometimes go unchecked. It isn’t with every cartoon, but some shorts of his feel as though Bugs is bullying for the sake of bullying and gets let off the hook too easily. Even Leon Schlesinger thought so, dictating that a dog committing suicide was much more pleasant than Bugs shooting the dog in the mouth.

Thus, we enter the fated moment that played a part in ending Avery’s career at Warner’s. This is how it plays in the cartoon: Willoughby falls, with Bugs shortly behind. Both meet amidst their falls and plummet to the ground together, shattering the eardrums of the audience through their incessant screams and Treg Brown’s plane falling sound effects. This entire charade persists for about 43 seconds. That may not seem like a lot of time on paper, but it certainly is when viewing the final product. Especially given that the scene makes a point to be as monotonous and repetitive as possible.

After a series of recycled shots and still incessant screaming, Bugs and Willoughby—ever miraculously—manage to apply their brakes at the same time (breaking the 180 rule in the process, as they’ve suddenly switched positions.) The animation embraces this sudden deftness by having the landing be as soft and gentle as possible, both characters seeming to float onto their feet like a feather.

“Nyeh—fooled ya, didn’t we?” Declares an ever abrasive Bugs. Inclusion of “we” indicates that, finally, for once, he and Willoughby are on the same wavelength. Both are complicit in heckling the audience (if not completely assaulting their senses.)

“Yeah,” guffaws Willoughby as the screen goes dark. His voice and music both seem to cut off suddenly; the addition of a camera pan left likewise hints at information taken out of context.

That’s all, folks!

Clearly it’s not. Quite a few of these cartoons boast lost endings, and many—if not all of them—are much more coherently disguised than this one. Whether in 1941 or 2023, it’s exceedingly clear that something is missing. What was missing, however, was the subject of debate for decades.

Avery’s own recount of the situation was this. Bugs and Willoughby take another fall shortly after, amounting in two falls total: two falls worth of screaming and falling and other abrasive cacophonies. Before indulging in the fall, Bugs announces to the audience: “Hold onto your hats, folks—here we go again!” just as the cartoon reaches its end.

Innocuous enough, seemingly. In actuality, Bugs’ line is a reference to a crude joke that was popular at the time, insinuating that was the reason behind the ending’s excision. It should be noted that acetate recordings of Daffy Duck in Egghead survive; in that, Daffy announces “Hold your hats, folks—here we go again!” before launching into his song number of “The Merry Go Round Broke Down”. As it stands in the cartoon, his line was changed to “Hold your seats, folks—here we go again!”

However, Avery’s recollection of the event isn’t entirely true. In his book Hollywood Cartoons, historian Michael Barrier notes that Bugs and Willoughby take two more falls rather than one, amounting to a total of three falls. That’s a lot of excessive screaming and repetitive action.

Indeed, that seems to be the fated outcome. Thad Komorowski kindly relayed a scan of the cartoon’s original transcript drafted in 1941; sure enough, a quick look reveals no such line about holding onto any hats or any other crude allusions. After Willoughby repeats Bugs’ statement of “fooled ya”, Bugs declares: “Well, here we go again!” Thus initiates the second fall… which initiated the second “fooled ya” exchange word for word. That, too, results in one final ear-splitting fall as the cartoon comes to an end.

To quote the wisdom of Barrier: “If Schlesinger did order the cut, he was not acting arbitrarily.”

Indeed, it seems that Avery—no pun intended—went just a little over the edge in his desire to push the nerves of the audience. Such has been a recurring theme of his work for years, and would continue to be. One Ham’s Family at MGM has the main character scratching nails on a chalkboard to “heckle you people out there”, and it is as every bit grueling as it sounds. And boy, does it certainly sound.

Regarding Avery’s flawed recollection of the event, I concur with Thad’s interpretation in that it seems Avery felt some embarrassment for his misfire and didn’t want to recount it. Especially given that he was, by all accounts, a notorious perfectionist, he would have known in hindsight that it was a ballsy maneuver that wasn’t in his (nor the audience’s) best interest. Likewise, it’s easy to feel sympathy for him, especially at the time of the cartoon’s conception. He thrived off of subversion and completely breaking the rules, traversing new ground and throwing expectations out the window. Daffy came from taking such a risk. Bugs came from taking such a risk. To him, this constant barrage of falling and monotony was just another risk that he had to take, another subversion of the audience’s expectations that nobody had done before.

For the longest time, this was my favorite Tex Avery cartoon. Period. No room for debate. I loved the drawings, I loved the directorial tone, I loved the characters, I loved the brazenness. When asked my favorite Avery cartoon, this was always my immediate answer.Prefacing a paragraph with “for the longest time” indicates my opinions have since shifted: yes and no.

I still love this cartoon to bits, and examining it from the outside in has done nothing but further justify my infatuation. I still adore the drawings, I still adore the endearing charm of Willoughby, I still adore the novelty of a more antagonistic Bugs. I adore Johnsen’s backgrounds, I have a newfound appreciation for Mike Maltese’s contributions to the cartoon. I even love the titles. This is still very much a cartoon I revere and will continue to.

However, I don’t know if I can call it my fully fledged favorite anymore. Not because I think it’s flawed or bad—namely, my priorities have shifted, and I’ve fallen in love with so many other aspects of Avery’s filmography that it’s truly difficult to discern a true favorite. At least from his Warner years.I first saw this short in a time where my knowledge of Looney Tunes mainly stemmed from Bob Clampett’s filmography and a handful of other sporadic outliers. I binged all of Clampett’s shorts chronologically in submersing myself into these cartoons. Thus, my enthrallment with this short largely stemmed from the idea that it seemed so close to the work that Clampett would be doing in the early ‘40s. A logical conclusion, given that Clampett adopted Avery’s unit. Scribner’s drawings felt like Scribner’s drawings. Bugs’ wiliness was comparable to the wiliness in Clampett’s cartoons. To me, this was a pseudo-Clampett cartoon, which is obviously a testament to its quality. Every cartoon ever must be ranked on a scale from most Clampett adjacent to least Clampett adjacent—anything that dares to stray from that is complete and utter garbage.

Dripping sarcasm aside, my tastes and awareness of these cartoons have (thankfully) matured in the near four years since. I’d be lying if I said that still wasn’t a deciding factor in my enjoyment of the short, if only subconsciously—Rod Scribner’s distorted, manic drawings remain some of my favorite parts of the film. However, that it remains such a strong and amusing film in spite of such dismemberment is a testament to Avery’s strength as a director. It’s so easy to get absorbed in his mindset, his direction of the characters and the tone. I find myself pardoning directorial “oversights” in this one more than I would other cartoons, because they stem from such an air of confidence—does Avery cut too quickly to this shot, or is it a deliberate attempt to surprise the viewer? 82 years later and I’m still surprised, still entertained, still shocked, so clearly he’s done something right.I’ll write a much longer “in memoriam” for Avery upon our dissection of Crazy Cruise, when we’ve finally met the end of the backlog. Even if the end of this short ended up as a misfire, it’s incredibly telling about the kind of innovator and creative he was. So few people would stick to their guns like he did. There’s a bravery in taking a risk—even more so when that risk fails and backfires.

Likewise, as mentioned in the introduction, this blunder was possibly one of the best things that could have happened to him: it offered him an excuse to seek new ground, embrace his own vision, and culminate some of the greatest cartoons known to man at greener pastures. Something something omelettes made from broken eggs. Or, in this case, falling rabbits and dogs.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment