Release Date: July 5th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Fanfare, Building, Spitfire, Newsboy, Draftee, Horse, Soldier, Panting, Rochester), Billy Bletcher (Draftee), Jack Lescoulie (Jack Benny), Robert C. Bruce (Announcer, Narrator, Citizen Sugar Kane), Bob Clampett (Chicken)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

With war on the rise, tensions were rising even higher. US involvement loomed closer and closer—more and more people were registering for the draft, unknowingly reveling in the freedom of free choice. It would only be a matter of months after this cartoon’s release when all men between the ages of 18 and 65 would have no choice but to register. In fact, this cartoon’s release only comes a few weeks after the start of Operation Barbosa, in which the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. Such marked the largest land offensive in human history.

|

| Wartime era drawing by Bob Clampett. |

Propaganda films would soon begin to pepper and overwhelm the theatergoing landscape—similar to The Depression, whose vestigial effects were still being felt, audiences despaired for relief, encouragement, or camaraderie of some kind. Whether an uplifting, bombastic message of jingoistic empowerment or just the reassurance of “you ain’t alone, brother”, there was a demand to be heard and seen. A strong craving for unity in a tumultuous era of divisiveness.

So, again, what better way to satiate such a craving through a hearty dose of propaganda? Better yet—a hearty dose of propaganda in cartoon form?

Allusions to war have grown more concentrated in these cartoons. One could make the argument that they’ve always been there, and they have—Bosko’s Picture Show notably being the first cartoon of any kind to caricature Hitler—but the looming threat of US involvement in the war has certainly been reflected in the media landscape. Porky’s Snooze Reel, of which this cartoon is almost an informal successor to, had its own vignettes showing off various tanks and latest advancements in wartime technology. Of Fox and Hounds facetiously credits the Avery unit through their draft numbers. These cartoons are a reflection of the culture of their time, and the results are surely shown.

Even with all that in mind, this may very well be the first truly WWII focused cartoon for Warners. It puts an undeniable spotlight on the topic and is an entire spot-gag/newsreel parody related to wartime gags. There’s even a point to emphasize the unsettling, alarming notion in how quickly the war seems to be advancing through rapid newspaper headlines. Granted, this short is more observational rather than unabashedly chauvinistic, but the point remains: the tides are continuing to turn. We have our first true wartime cartoon.

Capitalizing on all of the above developments, the cartoon itself seems to acknowledge the gravity of its role right from the start. Instead of dissolving to a fancy, spiffy title card, instantly greeting the audience with names that they’ll soon forget after leaving the theater, the short instead opens with a gaping cannon. Pointed directly at the viewer, the cartoon momentarily adopts an attitude of confrontation as the audience is cornered into engagement. The cannon isn’t aimed at the camera. It’s aimed at you, the theatergoer.

The effect is particularly striking, especially upon the reveal of the cartoon’s title (its name derived from the 1941 Frank Capra film, Meet John Doe) after it fires out of the cannon, revealed through dissipating smoke. It’s certainly jolting and a lot to digest in the short’s fledgling seconds; one could make the astute argument that it’s a metaphor for the suddenness of war—there is no grace period of waiting, no pleasant preparation beforehand. It’s jarring, it’s alarming, it’s unexpected.

Or… it was just an inventive way to start the cartoon that happened to look cool. Clampett’s intentions are almost positively more aligned with the latter mindset than the former, but the point remains.

A sense of purpose regarding the opening titles pursues through the musical orchestrations. Following the reveal of the title, a bugle blares its call to arms, accompanied by the roll of a snare drum… only to dissolve into a last minute jazz riff as the actual opening to the short ensues. Such a breach of convention insinuates the format of the cartoon; it’s a newsreel parody, yes, and deals with the subject of war, but it isn’t intended to be a depressing slog. Gags will be involved, and expectations will be subverted. There’s a reassurance of leisure—odd as it may be to deduce about a cartoon that deals with war. Such a swinging riff seems to symbolize and personify that mischievous nonchalance. All is not as it seems.

That same grandiosity extends to the short’s formal introduction. Robert C. Bruce has the distinction of playing not only the cartoon’s narrator, but the announcer as well (two wildly different and unique roles, of course.) The sound of his voice booming atop the reused layout of a theater from The Film Fan intends to excite audiences of both kinds: fictional and actual.

Introducing Porky as “that star of stage, screen and radio”—outside of just being a cute self aware nod—serves as a fascinating historical footnote. At this point in the middle half of 1941 (and especially whenever it was produced earlier, likely in the latter half of 1940), it’s true he still had more star power than Bugs and/or Daffy. Bugs may have been turning more heads and garnering more whispers at the time of the short’s release, but Porky still reaped the benefit of seniority.

It would be within the next year or so when the tides would change and Bugs was unequivocally the star of the show. Daffy too, to a lesser extent—shocking as it may be to even say (and in a brief moment of candidacy, I concede that it’s one fact that I genuinely have the hardest time wrapping my head around and truly struggle to share the perspective of the theatergoers), he wasn’t as well known or beloved by audiences. Trade reviews even in the early ‘50s just label him as a nameless duck. Any notoriety was more likely to stem from the comics than the actual cartoons. Nevertheless, regardless of public reception, he too was stepping into his own and blossoming into a character independent of Porky’s guidance.

Thankfully, Porky still has the benefit of longevity on his side (and would even outlive Bugs in terms of theatrical lifespan), but his role as the tried and true, unequivocal star and face of the shorts would be replaced. It’s fascinating to hear him called a star of stage, screen and radio at any point in time, but especially now, when Bugs’ grip on the masses was so imminent. Very much furthers the cartoon’s role as a time capsule.

Back to the cartoon. We aren’t actually supposed to know it’s Porky—at least, not yet. Sticking with the wartime theming, Bruce introduces the star as the illustrious Draftee 158 and 3/4. The joke works even today through such a stark juxtaposition between his lofty, hyper introduction—implying that everyone knows of this certain star—and the underwhelming anonymity of a draft number.

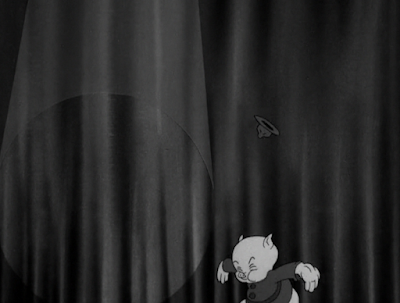

Ditto for the spotlight and adjoining fanfare fixating on nothing. Clampett’s conviction to the joke—and subsequent “suspense”, stringing out the audience’s expectations to build further anticipation—turns a politely dumb gag into a production of its own. It’s not even an issue of technical difficulties; there’s nobody to turn the spotlight towards. The audience is left to ponder how this notorious subject teased before them could ever make it as a star of the stage if he can’t even be bothered to be on stage in the first place.

Thus, to overcompensate, Mr. Draftee 158 and 3/4ths jumps onto the stage with a proud, extravagant flourish. His jumping and posing is amusing through how wholly arbitrary it is. Especially given that he doesn’t even land in the line of the spotlight—if a desire to showboat was his goal, it wasn’t entirely achieved. Not if the audience can’t even see it. Having his hat plop onto his head at a slightly delayed interval makes Porky, in turn, feel more static, thusly furthering the joke. He conducts himself with an overwhelming vacancy that proves helpful for the comedic purposes served. For the purposes of this cartoon’s introduction, he is an enigma.

Spotlight hastily swings over to Porky after a beat, as though realizing he’s not going to remove himself from his cued pose anytime soon.

Enter some gorgeous animated handiwork courtesy of John Carey. While this is admittedly much more tame than some of the animated feats he has and will continue to accomplish, this particular scene will always be one of the first scenes I think of upon hearing his name. It looks and moves nicely, serving its purpose of carrying a relatively lofty stretch of dialogue, but isn’t nearly as indicative of his talents as other scenes that would probably be more fitting associations.

Regardless, it comes to mind due to it being the first time I really paid attention to his handiwork. Seeing the cartoon for the first time, I had no idea who or what a John Carey was—just that this scene moved oddly and intriguingly, and like no other animator. After placing a name to a drawing style (thank you Devon Baxter!) it was then I became more conscious of his work, being able to piece together and surmise his draftsmanship in any scenes that seemed to boast a lot of idle movement, drawn tightly and with a sharp eye for construction, or, in a more particular case, drawing Porky with a wide snout and more fullness.

This likely doesn’t come as a surprise to readers of this blog, but he’s now one of my all-time favorite animators and cartoonists. It’s thanks to this seemingly inconsequential scene in this seemingly inconsequential cartoon that it’s such a case.

While certainly not one of Carey’s most climactic animation assignments, he does excel in inciting visual interest—especially for a scene so reliant on dialogue. Weighted head tilts, turns, and nods ensure that Porky is a real, living being, able to flaunt his depth and construction through a variety of perspectives. Such an illusion of life is imperative for a sequence that intends to speak to the actual audience of theatergoers as much as it does the fictional constituency. Carey's attentiveness extends to even animating the breath that Blanc takes between lines of dialogue.

Acting is comparatively subtle; that, too, arrives as a strength. One particularly strong detail is having Porky reflexively wring the corners of the jacket in his hands. A somewhat recurring tic throughout multiple cartoons, it’s an especially thoughtful addition here—it could communicate an endearing bashfulness on his part at speaking directly to an audience of hundreds just in the moment alone, and a total of thousands in theaters across the country. Or, it’s just an absentminded habit, an improper stage presence that serves as an amusing, deliberate incongruity against Bruce’s claims of being a star of the stage—one would assume Porky would be more accustomed to nipping such candid behaviors in the bud if that were the case.

It’s mainly a believable piece of character acting that keeps him grounded and endearing. A reminder that this isn’t some notorious yet similarly anonymous, vaudevillian draftee preaching to the audience—it’s Porky Pig.

His speech would have had a striking effect for theatrical audiences. The scene is positioned so that he appears to look down at the viewers rather than directly at the camera; there may seem to be a dissonance watching it on a phone or computer today, but with the positioning of the screen in the theaters, he would have been looking directly into the audience. Thus, the illusion of him addressing them directly is much more personal as it is believable.

Such a maneuver likewise proves beneficial for the wartime punchline it encourages. Hyping up the coming newsreel, Porky heralds promises of military secrets and inside scoop… but on one condition:

“So if there’s any ihf-ih-i-eh-fifth columnists in the audience, uh-will they eh-peh-pih-ihh-puh-pih-ehh-please leave the the-eh-th-eater right now?”

An elongated beat follows as he smiles vacantly at the audience, implied to be watching for anyone leaving. Ample time is allotted for real audiences to laugh at the subversion and metaphysical humor, which works well with Porky’s intended patience. Almost as though he’s waiting for the real audience to stop laughing as much as he’s waiting for the fictional saboteurs to depart. As tame as it may seem nowadays—especially divorced of the context in which it was created to be viewed in—this was a startlingly effective fourth wall break that likely got a lot of amusement and novelty from multiple audiences.

His polite “Eh-thuh-thih-ehh-thank you,” is the ideal topper. It introduces a finality to the gag, a solid beginning an end—the audience isn’t just baited into laughing because it’s subversive and only for that reason. Porky follows through on his promise for waiting for the fifth columnists to leave, which, in turn, is a dedication to the gag from Clampett and Warren Foster alike. Very well executed all around.

Thus marks the end of Porky’s relevance within the cartoon as he dips out into the eaves, never to be seen again in the remaining 5 and a half minutes. In a way, that’s one of the cartoon’s strengths—it doesn’t try to delude the viewer into thinking it’s a Porky cartoon. It’s implied that he’s the one presenting the newsreel (as heralded through the “PORKY PIG PRESENTS” unveiled on the screen soon after, a fractured, Warner take on the famous RKO logo), and that’s about it. There’s a transparency that is relieving more than humiliating—attempts to shoehorn Porky into the production often flounder. For example: Porky’s Snooze Reel. It’s best to have him on screen when he’s wanted, and off when he’s not.

Nevertheless, even the parody RKO logo is indicative of the antics bound to ensue, riding on the coattails of the information established through the introduction. Mel Blanc performs one of his earliest renditions of his “rubber band march” yet heard in these cartoons, which, in itself, communicates a playful disingenuousness.

Moreover, those noting that the radio tower seems particularly flimsy would be correct in their assumption. A cut to the following scene occurs just a bit too quickly for the information to register fully, but the tower buckles and warps under its own lack of structure. One could even argue that the quick cut—as much as it accidentally communicated an inarticulateness—is a punchline of its own, quickly sweeping the dirt under the rug in an attempt to safe decorum and face.

Everything about this cartoon has been falling at the seams. Porky’s introduction. His stage presence. Openly asking any spies to get out, implying that some unsavory characters may be attracted to the film. The opening to the film itself as slapdash as its preceding presentation. Clampett and Foster execute this with a comparative subtlety, which is where its strengths lie. The audience is trusted to read and derive their own opinions and thoughts from the introduction themselves—no spoon feeding of “this is meant to be silly”. It’s all executed with an unquestioning certainty; that sort of confidence in Clampett’s cartoons has been greatly missed.

Robert C. Bruce’s sudden introduction as a narrator is delivered more seamlessly than relatively synonymous circumstances in Snooze Reel. As mentioned above, making a point to establish that Porky is out of the picture lessens tensions from the audience feeling as though they’ve been aped of their pig primetime. Likewise, casting Bruce as the announcer that heralds Porky’s arrival moreover introduces himself to the audience—thus, the suddenness of this non Porky entity is digested with more ease.

As many attempts as there may be to establish the newsreel (and its subsequent presentation) as a total hack job, the art direction of the short itself certainly doesn’t skimp out. A title card heralding “America’s Defense Effort” is believably bombastic, a solid balance of values and hues in the monochrome color to embolden the composition. Imagery of the Capitol conducts a sense of pertinence; ditto for the slightly askew angle at which the layout is arranged, encouraging a dynamism. In other words, it’s a bombastic, austere painting that could easily be incorporated into a real newsreel with little difficulty.

Playing it straight—if only for a few seconds—has always been one of Clampett’s strengths. Granted, some instances are more successful than others, but his understanding of juxtaposition and how comedy flourishes best with a “control” is undeniably felt. That same philosophy is instilled here; impress the audience with elevated visuals to allow the broiling, purposefully juvenile punchline to thrive in comparison.

Sure enough, the amalgam of elevated art direction—some of the most sophisticated and controlled to grace a Clampett cartoon yet—results in a literal embrace of Bruce’s words: “This is the stuff from which tanks are made!”

Certainly in Clampett’s brand of transformational, literal humor, even he seems to acknowledge that it’s a dumb joke. It is. However, it registers thanks to the laborious set-up preceding it. Limited monochrome palettes are embraced to their full potential (a rarity in these black and white shorts), with white heat a strong antithesis against the pitch black kettles and foreground objects. Objects and machinery operate in stilted synchronicity, enunciating their fine-tuned mechanicalness. Layouts are strong, conscientious. Shots flow together in a manner that encourage coherency, but make each snapshot of the factory distinguishable from the last. Stalling’s churning music score ties the vignette down to its cartoon, lighthearted roots—especially through the establishing shot of the smokestacks chuffing in tandem with the music—but, overall, there’s a comparative sophistication and clear regard for said sophistication that allows the deliberately callow resolution to revel in its juvenility.

A spotlight dedicated to an aircraft factory humming follows the comedic same principle, but to a much less bombastic degree. Bruce’s stolid, illustrious narration offers enough of a buffer for it to juxtapose against; it does, however, possess a spontaneity that could be a detriment or a bonus depending on how one views it. It doesn’t have the benefit of beautiful, elevated art direction to make the punchline feel proudly disingenuous in comparison. At the same time, it doesn’t need that benefit. Especially not after following an example of that very principle, potentially encouraging a monotony in the flow of shots and tone.

Instead, sophistication in cinematography succeeds the shot, inducing the aforementioned variance and balance in tone for the betterment of the audience’s intrigue. One of Clampett’s continued successes is his framing—while not always an aspect he reigned in, shots that do go out of their way to appear artsy and engaging are almost always executed with a conscious regard for how the shot sits in the composition. Steel beams corral the aircraft carriers, guiding the eyes of the audience, but are approached so that the framing seems accidental and natural rather than cold and purposeful. The camera seems to peek in on secret affairs—not having the convenience of the layout handed to the viewer on a silver platter. That sense of confidentiality, of being a fly in the wall, engages the audience all the more.

“In front of us is one of the famous English spitfires.”

Its punchline is a surprise to nobody, but is made endearing through Blanc’s rapid spitting sound effects and energy in the animation. A mischievous whimsy prevails—it’s too hard to be a stick in the mud over such an inconsequential gag. Turning the propellers of the plane into a very small, subtle mustache is a particularly inventive detail that sells the sudden anthropomorphism.

It almost seems as though Clampett has too many ideas for this cartoon. This is in no way a detriment, as the pacing of many of his prior shorts within the past year or so have suffered tremendously from the inverse. It doesn’t even come at the sacrifice of coherency—punchlines and intent of the gag all read. Just that there seems to be a surprising briskness moving from one segment to the other. A montage of still images depicting machinery being produced in the war is ushered in surprisingly quickly after the spitfire gag, and even that is soon usurped by a segment dedicated to the draft.

Regardless, it’s much more an observation than a critique. Such an eagerness to get down to business is certainly not taken for granted.

Antithetical attitudes in cinematography contribute to the fast paced mayhem of the war: giant, blocky letters spelling out “DRAFT” are blown away off screen with Clampett’s usual flair for mischief and literality, only to be followed by a smattering of photorealistic newspaper headlines. Using real newspapers induces a gravity to the situation, reminding the audience that it isn’t mere cartoon hijinks. The montage is a clear send off to one of the most beloved tropes of ‘30s and early ‘40s filmmaking: a plethora of newspaper headlines drowning the screen. Such a connection bridges the audience to reality—the disconnect is intended to be swift and alarming.

One headline in particular touts a publication date of August 28th, 1940, potentially shedding insight into the production timeline of this very cartoon. That newspaper is selected as the chosen vessel for further tongue-in-cheek wordplay, as well as bearing the distinction of the first Citizen Kane reference in a Warner cartoon. Clampett, ever the film buff, in particular seemed to hold a reverence (or at least fascination) towards the film, as this certainly wouldn’t be his last acknowledgement. The reference is particularly impressive given that the film hadn’t even been released to the general public at the time of this short’s release. It was shown at the Palace Theater in May of 1941, but would take until September to reach theaters nationwide.

It likewise presents an opportunity for Bruce to step out of his usual typecasting—or, at the very least, from one typecast role to another. His impression of Kane is that of an old, ornery coot, channeling his old man voice that has spotted a handful of cartoons before. Hearing him switch so effortlessly from the safety of the condescending narrator to a wily old man is certainly impressive and novel; one can still tell that it’s him doing both voices, but such is where part of the endearment stems from. Even the mere decision to make the switch at all serves as insight to Clampett’s directorial tone; it adds fluff and mischief to a deliberately groan inducing pun that likely would have floundered if Bruce maintained his stolid narration. A deliberately lighthearted tone that seems surprising when discussing the perils of the war. Such is the mission of the entire cartoon.

Seeing as much of the cartoon builds its structure upon switching between non sequiturs, finding a way to maintain the freshness and intrigue of transitions is imperative. Using the same dissolves or cuts or fades to black all in a row has a tendency to be monotonous. Thus, such could leech into the audience’s interpretations of the gags which, while funny, may not land as effectively if the structure of the cartoon is so repetitive. Thus, the black iris that swallows the screen and fades into the next screen summons the exact sort of novelty needed. Clampett has always been a fan of iris transitions, even in his ‘30s cartoons—typically that of a transparent iris wipe from one to the other. Here, the opaque black iris combines two different kinds of transitions in one, encouraging a tone that is fresh and spry. A few of his shorts from around this time would feature a variety of iris transitions, indicating a regard for how the flow of the cartoon impacts the viewing experience and coherency.

“All over the country, men of draft age scan their draft board lists for their number and discuss their chances of being called up.”

John Carey’s handiwork is again exceedingly evident in such a vignette; not only through the way in which the characters move, but his design sensibilities as well. Said men are both drawn to two extremes and fit right at home on Clampett’s world, executed with a playful bulbousness that is fondly reminiscent of more crude foundations (a glorified sensibility of newspaper cartooning) but streamlined and organic enough to fit comfortably in the demands of the early ‘40s cartoon landscape.

Likewise, it’s only logical that their voices be as asinine as their designs. The tall, chain smoking derby hat wearer who nonchalantly dips his ashes into his smaller cohort’s hat, supporting his careless disregard for the draft board, boasts a nasal, shrill, grating caricature of a voice. It’s hammy, but certainly not out of place. Carey’s acting is solid, whether through indications of personality (as again evidenced through his disposal of ashes) or maintaining a physical cadence to support his lines.

“Besides—yah much too short,” he reassures to his vacant comrade. “Dey’d nevah take a little runt like you!”

A transparent iris wipe is sharp and quick to match the whiplash of the punchline. Having said runt be on stilts isn’t only an amusing visual, but a playful admission of the big runt’s own words: he was too short. Granted, they found a way of compensating, but the snob, Brooklyn-accented nasal drawl didn’t spout complete lies nor complicity.

Likewise, it’s only fitting that the runt’s voice be the booming, deep timbre of Billy Bletcher’s. Subversions extend beyond punchlines, but audience expectations of personality and character as well. Here, he recites the same acerbic wisdom heard recently in Clampett’s A Coy Decoy: “You, and your education!”

A cross dissolve transports the audience to a personal look of the army camps themselves, indicating that grueling conditions aren’t reserved for training or the front lines. Care and regard for cinematography extends even to the most domestic of affairs, whether that be bugling or eating in the mess hall.

Particularly the latter. Here, the troops gorge themselves with wartime delicacies, indicated purely through projected silhouettes and shadows. Clampett makes clever use of negative space, filling each open crevice with the silhouette of a draftee. This produces an uncanny effect of sorts, in that the resulting visual is deliberately orchestrated, unnatural, geometric. It thankfully doesn’t read as stilted or as a shortcoming in proper perspective. Rather, its intent as a clever piece of staging is evident, thriving humbly in its oxymoronic showiness. It’s meant to seem staged and synthetic, as that immediately captivates the eye of the audience. Incongruities between the gracefulness of establishing the visual and the decidedly inelegance of soldiers stuffing themselves is likewise effective.

“...as the great general Napoleon once said: ‘an army travels on its stomach.’”

Once more does a literal depiction of Bruce’s words ensue. The mechanical, orderly and motivated movements in tandem with Stalling’s triumphant music score give a solid foundation to another proudly juvenile gag.

Spotlighting a machine gun nest obeys the same philosophy. Casting the action in silhouette bestows added visual intrigue, differentiating it slightly in its identity from the former gag’s structure. Ditto for the addition of a topper—three baby machine gun chicks flitting out of the literal nest—which adds a slight extension to the visuals. It, too, is a politely dumb gag, but one that makes attempts to embrace its naïveté rather than shun it. Clampett himself performs the clucking noises of the mother “hen”; many a chicken noise heard in these cartoons often came from his mouth.

Segueing to a barrage of army horses follows the same flow of consciousness, even if the tone seems drastically different. It, too, results in a lighthearted, fun, resolution—said horses performing a conga, abiding by Bruce’s observations of their South American roots—but opens on a rather solemn note. Heads bowed, skies a murky gray, opaque silhouettes oppressive in their darkness, commenting that “the horse still has a place,” almost seems grim rather than a proud factoid. Even animals must be victim to and complacent in such violent warfare. Thus, the tonal whiplash with the punchline is effectively striking in contrast.

Visual intrigue regarding transitions and wipes still persists, even four minutes into the cartoon. Clampett evokes a transition that hasn’t been used in any of these cartoons yet—and, while definitive, there’s certainly a possibility that it won’t be seen again. Here, the screen obeys a simple horizontal wipe between two scenes. These shorts have touted similar vertical or horizontal line wipes before, seen in many a live action counterpart. However, none of these shorts has followed a black wipe. It’s the same exact philosophy of the black iris in—a regular wipe, just opaque.

The maneuver is quick and swift, and the flash of black that cascades up the screen almost seems like an error at first glance. It seems so menial to comment on in the grand scheme of things; the first Warner cartoon of many to place an unabashed focus on the perils of war, indicating the growing turmoil overseas and the mindset of anxious Americans in the early ‘40s, and the most consistent observation is the way in which one scene moves into the other. Regardless, it, too, like everything else about these cartoons, is a science. A science that (if only on a subconscious level) dictates the focus and intrigue from the audience. These little details are important in encouraging coherency and flow.

Enter a more morose tone as Bruce demonstrates the new “anti-tank gun”, a hilariously obtuse yet illuminating name for the machinery and its intended purpose. Serving to blow up tanks on the spot is one way to be described as “anti-tank”.

More elevated art direction and layouts persist through a carefully symmetrical shot. The cannon commands the audience’s direction, with the horizon line arranged for the oncoming test tank to naturally creep into focus. Likewise, more subtle means of framing (such as the barren trees in the background, curved at an angle that points towards the tank, or the barbed wire fence that guides the audience’s eye back to the middle) further the symmetry. A metal frame enveloping the screen is a geometric, orchestrated, mechanical framing device—juxtaposed against the organicism of props and background objects furthering the same mission, the layout boasts a balance from all fronts. Very motivated thinking.

Bruce’s vocals are just as imperative to the action unfurling on screen, if not often moreso. He boasts a hushed anticipation that quickly transforms into strained intensity when the cannon doesn’t fire, missing its target: his cries of “FIRE, FIRE! FIRE! FIRE! What’s the matter—why don’t they shoot!? What are those gunners doing!?” is amazingly visceral. Many of the spot gag cartoons boast synonymous moments of tension where Bruce’s vocal abilities are put to the test, often having him yell or shout at the subjects on screen. Given the gravity of this situation (and the exaggeration of Clampett’s vocal direction), this is easily one of the most tense yet. A lighthearted punchline is surely on the horizon, but the suspension of disbelief and immersion in such friction is at some of its most believable and palpable here.

As is one of the short’s themes, such intensity is best brought out through a solid juxtaposition. Here, Clampett once again utilized his fascination of pop culture as a means of a punchline: two soldiers comparing the sizes of their cigarettes isn’t a random, bizarre tangent, but a reference to a Pall Mall cigarettes ad campaign depicting the same scenario, proud in their elongated cigarette sizes. Stalling’s comedic “laughing” music score may be a bit too obtuse, as the dopey, buck toothed soldier’s inane chortling and voice is enough to indicate a lack of decorum. Regardless, it achieves its goal of serving as a powerful antithesis to such a strained, intense moment.

Clampett and Foster stay on course with their cannon theming. The punchline of the cannon falling flaccid and panting after each fire is nothing new, whether to Clampett’s cartoons (Ali-Baba Bound’s climax features a synonymous, repetitive deflation) or the medium of animation as a whole (the 1927 Oswald cartoon Great Guns likewise features the same deflation gag). Regardless, its execution is in character for Clampett’s reigning directorial home, making it feel right at home within the context of the cartoon.

Stylized art direction persists when shifting over to army testing grounds, filling the viewers in on the latest wartime machinery being perfected. A sign warning passersby to keep out is large and imposing, extending even beyond the bounds of the camera to further its menacing warning. A barbed wire fence cryptically encases the arena, with barbs in the foreground painted in white to juxtapose against the black fence post—it’s not only a striking means of stylization, but a visual reminder of the barbs’ presence. They don’t stop just because the screen stops.

“Here is the latest weapon: a land destroyer.”

Propping it up as 100x faster and more effective than a tank, expectations for this enigmatic vehicle are high. Having the camera track the movements of this destroyer maintains an urgency and upholds its credibility as an unbelievably fast force of nature; so fast that even the camera struggles to keep up with it.

Animation of the vehicle itself is one of the cruder scenes of the cartoon, but, given that it’s shot at a distance (much less zipping across the screen in flashes), it’s understandable. Demonstrating it colliding into a nearby house prompts some particularly stilted effects animation of the collision, but lingering on the intricacies of how the house falls apart isn’t the intention.

Moreover, such rigidity proves to be a punchline in itself: the destroyer mows down a line of trees in the background one by one, prompting them to hang in the air before collapsing nearly back into place. That, paired with the comparative lugubriousness in which the machine exerts its mission, offers another strong contrast that renders the audience more engaged in the maneuvers of the machinery.

“Hey, stop and let us see that machine!” Silhouettes of its pilots are crude and simplistic, appearing more as flat stick figures than actual human beings. Such anonymity is imperative in protecting the identities of the soldiers…

…which the resolution hinges on. Enter caricature artist Ben Shenkman’s renditions of Jack Benny and Rochester (the latter of which unfortunately suffering from the monochrome color scheme of the cartoon, an already egregious caricature made even more flagrant and reminiscent of minstrelsy by coloring his skin pitch black). This, like the Pall Mall cigarette tangent, isn’t a random celebrity caricature for the sake of random celebrity caricatures.

The jalopy they pilot is Benny’s trusted steed, Maxwell, often the subject of ridicule on his radio show for being the slowest heap of junk around. Mel Blanc himself provided the sound effects of perhaps the most famous car in radio history—so famous that it was remembered in both his and Benny’s obituary. Ironically, the sound effects for the convulsing car here (which is animated much more attentively and gracefully than the prior sequence) are mechanical clangs and honks—no Blancian huffing or puffing to be sound. A missed opportunity, especially given Clampett was so gung ho on inventive, mischievous sound effects, especially those coming out of one’s mouth. (His own, for example—the iris out “beeeeoo-wip!” and “boip!” sound effects are still immortalized in modern cartoons to this day.)

Enter more newspaper headlines, this time with a comparatively more triumphant tone. Eagle eyes will be able to make out that the headline date is now April—perhaps once again indicative of the short’s production timeline. Clichéd as the trope may be of spinning newspaper headlines, it works well within the context of this short. An effective means of establishing exposition without spoon feeding it through narration alone, and consistent with prior plot devices instilled by the cartoon.

Focus heads to the skyways as planes take off into the air; contrasting with a yet again heavy, prideful tone, the effeminacy of the plane teetering on with its feet and skipping into the air keeps antics light and airy. Not the most thrilling of gags, but fitting for its place in the short—especially given that the twinkle toes maneuver is more of a side effect to the scene than a dedicated focus.

Likewise, a wide shot of the “flying fortresses” peppering the sky is truly impressive. Planes are maneuvered on multiple cel layers, allowing them to fly in slightly different intervals from one another. Thus, the illusion of depth and perspective is much more convincing through so many contrasting elements operating at different speeds and scales. Likewise, the skies almost feel more full with so much information to digest. The effect certainly wouldn’t be the same if all of the planes moved at the same speed at the same time.

So smitten with the shot, Clampett would even reuse it at the end of another wartime spot gag cartoon: 1942’s Wacky Blackout. Given the grandiosity of the shot, the recycling gets a pass. It is genuinely captivating.

Speaking of reuse, a shot of ships bobbing in the sea as a representation of the Navy is a piece of recycled footage somewhat native to Clampett’s cartoons. His What Price Porky fashions the footage to fit the contextual needs of the short as a reference—the reference in question stems from 1934’s Buddy the Gob. Quite the throwback in terms of reused footage, but it does blend in relatively innocuously with the flow and designs of other machinery showcased in this cartoon. There’s certainly no way an audience member would have noticed the recycled footage.

“Powerful guns” so hyped up by Bruce result in the disappointment of a pop gun—the gag in itself is difficult to deem disappointing, seeing as it exists solely as a deliberate anticlimax. If anything, its intent to bait the audience into expecting something more grandiose is effective; even the dramatic up angle of the cannons indicates a severity and dynamism that is completely destroyed by the punchline.

A fleet of tanks offers their own comedic antithesis: jokes involving the warm invasiveness of the Good Rumor ice cream truck cutting into the action were especially prominent during this point in time. As reflected upon in the review of Holiday Highlights, the Good Rumor truck made regular rounds to Termite Terrace, much to the delight of many young animators and staff on their break.

There almost seems to be a sudden splice following the gag, as a jump cut to a newspaper headline with much more foreboding music seems to materialize out of nowhere. Clampett’s touted a variety of clunky cuts and transitions before, so it isn’t a stretch to chalk it up to a momentary lapse in directorial flow. It just seems odd in this short, given that he’s expressed such a meticulous regard for the way scenes flowed and interacted with one another prior. Something could have fallen to the cutting room floor during the short’s production rather than after the fact, and perhaps there wasn’t enough time—or, more realistically, concern—to remedy it. Speculation aside, the jolt is jarring.

Especially given the context of what it cuts to. A headline cryptically asks if America itself can be invaded and thusly involved in the war head-on.

“Are we safe from air attack?” Muses Bruce. “Supposing one day a fleet of enemy bombers suddenly appeared over the horizon…”

Viewers of today submit to the compulsion of checking the short’s release date: indeed, less than 6 months predating the Pearl Harbor attacks. It wouldn’t be the last time Clampett accidentally foresaw the future—Tortoise Wins by a Hare, released in 1943, features a byline in the newspaper about Adolph Hitler committing suicide. Two years before it actually happened.

Thus, the cartoon ends on an amalgamation of emotions. Foreboding and wryly cryptic, for those of us viewing in a post Pearl Harbor world. Playful and even optimistic in a pre December 7th world as Lady Liberty transforms her torch into a pesticide gun, knocking down the enemy jets like a swarm of stubborn mosquitoes. It communicates a message of hopefulness and chauvinism, that America is truly indestructible with the power of patriotism on its side. No harm shall come its way through liberty and justice.

Right?

For a spot gag cartoon—a wartime era spot gag, at that—this isn’t that bad at all. Clampett once again asserts himself as a studious observer of Avery’s travelogue and spot gag cartoons, as he adopts the format with little growing pains. Obviously, both directors have their varying pet gags, varying impulses and their own distinct tone of voice, but if one were to present a spot gag short from each director without their names on them to a regular viewer (ie not obsessive about animation history), there very well could be the assumption that both cartoons came from the same director.

Regardless, historians are able to trace Clampett’s distinct directorial identity to this cartoon. It’s a surprisingly deft effort, which, as mentioned before, always comes as a relief, especially following a downturn in quality that dominated his cartoons for the past two years. The gags featured in this short aren’t uproariously hilarious, but they’re certainly not bad by any stretch of the imagination. Even deliberately lame gags—of which there are plenty—revel in their assigned lameness and embrace their identity. Confidence permeates Clampett’s directing, which is an incredibly welcomed change.

Porky’s deliberate exclusion doesn’t sting as hard knowing that the short doesn’t try to kid itself. Thus isn’t a Porky Pig cartoon. It doesn’t need to be a Porky Pig cartoon. His limited time is used smartly, fulfilling his purpose and making his role—limited as it may be—clear. The audience isn’t left stewing in frustration, thinking about how much of a better cartoon it would be if Porky were shoehorned into every scene.

Clearly, the end to Clampett’s Porky embargo has done wonders. It would still be a little bit until he’d truly come into his own, shedding (most) of his bad habits and blossoming into his highest potential, but the freedom to direct the color Merrie Melodies and broaden his horizons, if only incrementally, is certainly paying dividends. His shorts boast a renewed energy in their execution that would only continue to grow. If not energy, then at least motivation. Comparing this short to Porky’s Snooze Reel reveals a night and day difference of attentiveness and engagement to the cartoon—perhaps that’s a fallacy, seeing as the short was co-directed by Norm McCabe to compensate for Clampett being out on sick leave, but many of the habits and faults in that short are traceable to Clampett’s sensibilities.

In all, it’s a strong short within the context of its time. A harbinger of both the uptick in Clampett’s directorial quality and the propaganda shorts to come. While it reads as much more middling today, one can still appreciate its novelty as one of the first true wartime Warner cartoons. This seemingly insignificant little quota-filler stands as an omen in more ways than one.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment