Release Date: June 21st, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Cal Dalton

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Worm, Crow)

(You may view the cartoon here!)Chase cartoons are an uncontested staple of golden age cartoons. If asked to represent the general time period today (say, in another piece of media), most default to either the stereotype of Fleischer-adjacent aimless bobbing or two characters constantly trying to pursue one another. It’s a shorthand recollection, and while these cartoons offer so much more than just repetitive predator versus prey dynamics, it’s certainly understandable as to how they’ve become a representative cliché.

Freleng in particular was a fan of his chase cartoons, and had been even during his previous tenure in the ‘30s. Now, however, his focus isn’t exactly on being a purveyor of the dynamic so much as it is finding ways to turn the chase cartoon on its head. The Cat’s Tale sought to offer a more metaphysical perspective as to why chase dynamics insist, who structures this hierarchy and why. Double Chaser, released the following year, serves as a humorous display of convolution that follows a similar philosophy teased by Tale.Sandwiched between the two is The Wacky Worm. It isn’t as openly subversive as the other two, and is certainly more obedient to its own format than rebellious. Nevertheless, that the prey—often intended in these cartoons as the one the audience is sympathetic towards—is a caricature of Jerry Colonna (who was incredibly funny and charismatic, but perhaps not exactly a shining beacon of cute and cuddly endearment) is enough to demonstrate that this chase cartoon isn’t like all others.

Indeed, Freleng establishes the difference almost immediately. Whereas most cartoons in this vain open with the camera positioned on the target, cueing him as the plucky prey that is meant to have the support of the audience, this short delegates focus on its predator. A mischief that almost borders on a flippancy dominates over suspense: the bird obliges faithfully to Stalling’s orchestrations of “Muchacha”, moving in strict tandem to the music as it crawls forth. The mechanics and polite asininity of the walk cycle are called to attention much more than any sort of chase dynamic. Why the bird moves the way it does is irrelevant—how is the priority.

So much so that the opening could be dismissed as somewhat aimless. Given the conviction of the bird’s movements, the audience assumes that his dinner lies right in front of him. That doesn’t seem to be the case; after the bird accidentally takes a spill over a cliff, a noise from off-screen is what grabs his attention. He operates at a comparative leisure that perhaps wouldn’t be the case if he had fresh, hot feed actively slipping out of his fingers. What seems to be painted as a playful pursuit isn’t much of a pursuit at all, and while that in itself could be taken as a subversion of the ever trigger-happy chase cartoon, muddiness of its intent (or lack thereof) seems to dominate.

Even so, the details and physics pertaining to his eccentric walk cycle are nice. Such a strict marriage between action and music is an uncontested Freleng staple that certainly shines throughout much of the cartoon. Having the bird suddenly cut across the “stage” and into the background introduces further depth into the composition, thusly rendering the environments more believable and livable.

Amusing to note when the cliff almost seeks to establish the polar opposite. Geometric and flat, the cliff just seems to end. It doesn’t feel like a natural organic cluster of rocks creating a supportive foundation, but, rather, a backdrop to serve the purpose as a gag. It’s possible that this flat cliff side wasn’t exactly the intent. Regardless, the geometry of the cliff is certainly helpful in furthering the spontaneity of the drop—the ground exists until it doesn’t.

Capitalizing on this unplanned interruption, Stalling’s music score is completely suspended as the bird recognizes his mistake and scrambles to reunite with solid ground. Such a directing decision calls attention to the folly, inducing a polite suspense as the audience is focused only on the bird’s attempts to get back. Likewise, it assets that the bird can be divorced of his musical origins; he isn’t a drone that can only maneuver to the hypnotism of a tango. A hypnotism that the audience succumbs to as much as the bird; long as the walk cycles may stretch on, the length and mundanity are helpful in lulling the audience into a predictability that is jolted upon the arrival of the cliff.

Gravity prevails over the bird. Execution of his fall suffers from some of the same aimlessness mentioned above; the length of the fall is polite at best, and the background boasts some perspective issues that makes it seem as though the bird is floating instead of interacting with his environments. It’s possible the short length of the fall was an intentional punchline (Art Davis’ Nothing but the Tooth, for example, demonstrates a great gag that amounts in about a 6 inch drop), but Freleng was a very purposeful director. One gets the sense that the brevity would have been more pronounced if it was the purport.

The bird nevertheless has greater priorities than measuring the length of his drop—such as identifying the obnoxious, loud, sustained sound of someone’s voice off-screen.

Friz Freleng deserves to be commended for potentially upping Tex Avery at his own game of seeing just how aggressively he can grate the audience’s nerves into nothingness. Perhaps the most obnoxious song number could be found in this very cartoon (and that’s saying something, especially given that Freleng was also the director of My Little Buckaroo, which boasted the most obnoxious number up until this point); it’s a solid introduction to our eponymous worm, who commands the attention of the audience before he’s even on screen.

Especially considering it takes 14 seconds to reveal what he even looks like. Mel Blanc yet again establishes his superhuman abilities by sustaining one, single, long note for all of those 14 seconds without straining for a second. While it may just register as aimless (albeit funny!) noise to audiences today, theatergoers in 1941 would have penned it as a Jerry Colonna impression more quickly, seeing as one of his signatures was to sustain a single note before diving into a song.

Here, the song of choice is “Daydreaming”—accustomed viewers of either this blog or these cartoons will remember that the 1939 Hardaway-Dalton effort Bars and Stripes Forever had a synonymous Colonna-fied rendition of the same song. Spectacle was a stronger priority in the former, as labeling the noise here as a “song number” is relatively generous. It doesn’t seek to pad out time, to amaze, to instill further musical brilliance into the cartoon. It exists solely to make the audience laugh, if not lose some semblance of their sanity in the process.

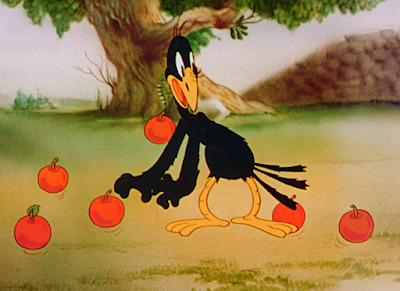

Lounging in an apple tree, the apples immediately give a motivation for the worm to be there. Worms hide in apples. Spontaneous as his introduction is intended to feel, attempts are made to introduce some sort of logic into it and form coherent tangents of a storyline—lounging in an apple tree is more decipherable and makes more sense to the audience than just having the worm pop out of a random hole or seemingly materialize out of thin air.

Entertainment value isn’t even solely on the vocal talents of Blanc. As he sings, the mustachio’d Colonna worm’s mouth twitches and convulses in an obtusely synthetic manner; the timing of said convulsions is where most of the success lies, as they seem completely random and don’t immediately kick in upon the opening of the worm’s mouth. A great piece of abstraction that embraces its zaniness, from both sight to sound.

Through the bombastic nature of his song, it doesn’t even seem like the bird is out to get him for food as he is to just shut him up. There’s a certain patience to be had as the crow glowers at him, not so patiently waiting for the theatrics to end—anyone truly starving or in dire need of a worm would have just plucked him up right then and there. Suspense and a grounded asininity is more important.

Perhaps too late, the worm does eventually recognize his company; a Colonna-esque exclamation of “My word! A bird!” serve as the magic words that kickstart the remaining five and a half minutes of run cycles and wacky antics.

The Wacky Worm largely exists as an exercise in ludicrous animation cycles. More and more, Freleng’s attempts to exercise the muscles of his animators is largely felt. Not that artistic evolution blossoms at the drop of the hat—the drawings seen here are the culmination of years of growth and collaboration—but The Trial of Mr. Wolf seemed to mark a turning point of sorts; the rampant exaggeration, whether through smears to convey speed or generally funny and outlandish drawings, the worm and bird adopt many of the principles seen and furthered in Wolf. Primarily the latter.

In particular, the worm’s obedience to Stalling’s tango music score is comparable to the wolf’s dainty prancing. Functionality is a slightly more prevalent driving force with the bird’s prancing than the wolf’s (which, of course, was the intent of the latter’s scene), but it remains amusing to compare. One wonders if the impulses or results with such a high level of caricature would have been the same if this short predated Trial instead.

Our introductory chase follows its own rule of threes: a spotlight on the worm. A spotlight on the bird. A spotlight on the two of them as both walk cycles converge, enabling a crescendo in action and engagement. Positioning the camera in favor of the worm delegates attention back to him, which, in turn, derives some semblance of sympathy. This is a cartoon that draws its focus from the antics of the worm rather than the bird—hence the title.

To ensure his own running chops can be as amusing as his pursuer’s, the worm’s running eventually devolves to a mechanical series of somersaults across a rolling pan. Yet another reminder, perhaps more obtuse this time, that this isn’t a stolid chase cartoon. Abstraction and caricature of the run cycles are a much larger priority than what spurred the running in the first place. It doesn’t get more obtuse than a run cycle that does everything in its power to divorce itself of a run cycle.

Seeking refuge in a hole doesn’t shift direction of tone or the camera—no bloated encounter on the bird pondering how to capture his stowaway victim. Instead, it too is another vehicle for further notional cycles; the worm turns towards the camera as he propels himself up and down like a loose spring, diving into the hole and doing the same underneath. Freleng’s musical timing bestows coherency to the vignette, instilling a purpose that melds the action together beyond visual noise for the sake of visual noise.

Granted, superficiality is the intent. Priorities of the sequence are to communicate that the worm is running from the bird, and that the imaginative, almost dismissively juvenile ways in which the characters run are the forefront. Visual acrobatics are the main takeaway. Not the who or the what or the when or the where or the why.

After allowing the music to dominate for the past thirty seconds, the Colonna worm cuts in with his own facetious commentary upon making an elongated dive: “Graceful, isn’t it?”

In one final breach of convention, the worm is able to scrunch himself up in mid-air and propel himself to his destination. A proud dismissal of grounded physics—especially given that the trajectory of his “graceful” dive almost seemed to indicate that he’d land into (or onto) something, seemingly following a very subtle arc. Shrinking into himself and launching like a loaded spring through the air deliberately betrays his own sentiments through a much more harsh, abrasive movement. Graceful indeed.

While they technically do, a shot of the worm diving in an apple juxtaposed against a wide shot of the bird approaching said apples feel as if they don’t hook-up together properly. Perhaps some of that dissonance can be owed to the painterly close-up of the apples, with their elongated stems and leaves; the opaque, cel shaded apples that are decidedly leaf-less are bound to stand out in comparison. A shift in background perspective isn’t as stark as the shift between the apples, and the location of the apple clusters isn’t entirely consistent. Out of all that is offered by the cartoon, this is an incredibly minuscule thing to nitpick. Nevertheless, slight as it may be, there is indeed a very subtle break that occurs that can be jarring even on a subconscious level.

Some fresh Dick Bickenbach animation offsets any cinematographical sins committed. Unsurprisingly, his animation is brisk, lively, and tangibly tactile, the bird conducting himself with a comparatively menacing urgency in his quick movements.

Likewise, such animation heralds one of the most amusing reveals of the cartoon: the bird is as obnoxious as the worm. His “I know where ya are! You’re in one a’ dese apples!” is equally as grating as Colonna’s song number, delivered with a purposefully stilted pedantic, harsh shout. While he may look mean, what with his sharp angles and permanently furrowed brows, the cadence of his statement almost indicates that he takes great pride in such a logical deduction. A deduction that probably took him just a bit longer to formulate than anyone else in the same situation. In other words, he’s a bit obtuse.

Flightiness of Bickenbach’s animation comes in handy for the worm—the stray apple that suddenly hops and convulses and bounds across the screen has a much stronger impact through such fast motion. It immediately registers as unnatural, thereby justifying any and all suspicions held by the bird. Easier to deduce that something’s wrong if an apple is convulsing away rather than just rolling or inching. Freleng’s penchant for musical timing likewise proves helpful in giving such actions a permanence and a spotlight of their own.

Moreover, Freleng insinuates that just because the running has come to a halt—for now—doesn’t mean that there isn’t more room for further amusing cycles. If anything, the nonchalance in which the bird creeps backwards on his tiptoes render the drawings all the more amusing. It’s a gesture that looks (and is) absurd, but feels completely casual and second nature. Contrast compels comedy.

As does surprise. Another sign of being a solid director is Freleng’s ability to surprise or subvert the expectations of the audience in tandem with the characters on screen. All of the apples scattering and hopping away at once is just as much of a shock to the viewer as it is the bird—there isn’t even any indication that the audience should have expected it in hindsight. Especially with how the apples move, the effect is successfully jarring and, to the bird especially, confounding. Bickenbach’s animated brevity really sells the clarity of such organized chaos, as a scene such as this one certainly has potential to fall into incoherence under the hands of a much less skilled draftsman or animator.

Admittedly, the apple bit does linger on for longer than is necessary, but understandably so. Enabling various apples of all sizes to run to and around and away from the bird justifies his conundrum, as there’s no way for him nor the audience to pick apart which apple has the Colonna worm. It’s a creative little vignette that demonstrates conviction to the idea, but could probably stand to be shortened by a few seconds.

Perhaps such a verdict stems from the reveal, in which an apple cracks against the stone wall and reveals the Colonna worm to be hiding inside. Given the entire production of the bit, one would assume that the resolution would be somewhat more climactic or invigorating. Nevertheless, the intent is to demonstrate that the worm was hiding in an apple and now his cover his blown, and said intent is communicated.

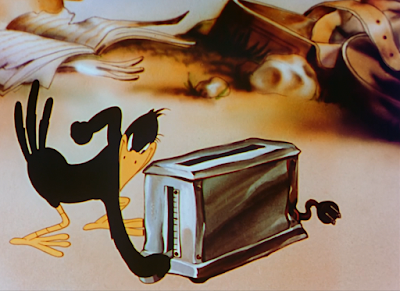

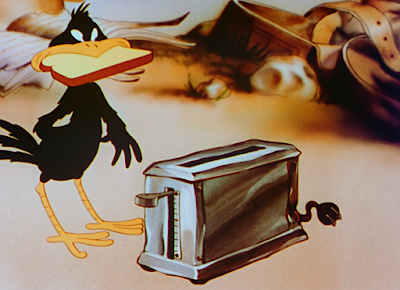

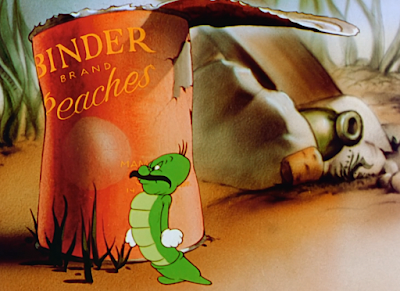

So, when all else fails, hiding in a conveniently available tube of toothpaste proves to be the safest course of action next.

Upon further inspection, the discarded tube isn’t nearly as big of a plot contrivance as it first registers. Viewers will note the discarded cans and bottles and other pieces of junk that soon pan into view, but the inclusion of a junkyard does seem to materialize out of thin air. Perhaps incorporating the junk into other background shots, even at a distance, would have been more helpful in telegraphing the coming segment. For now, it takes the audience a moment to recalibrate and understand that the toothpaste tube isn’t there just for the convenience of the story. Not entirely.

Bickenbach’s animation stretches into this vignette as well, identifiable from the limberness of his movements and poses to signature flourishes—additional brush strokes and action lines, or the ever telltale eye blink lines that communicate the bird’s befuddlement after the worm seems to disappear entirely. This could be said for most anything in any of these cartoons released around this time, but this same ordeal would have been wrapped up twice as quickly and abrasively if Freleng had directed the cartoon just a few years later. Nevertheless, Stalling’s musical orchestrations in tandem with the action keeps it grounded, and Bickenbach was the animator who was most indicative of the sort of speed and matter of factness seen in future Freleng endeavors. It looks and moves and behaves just fine for what it is.

Especially given that the toothpaste offers a vehicle for further exaggeration beyond the worm being pulled in and out of it. After realizing that the worm is indeed still in the tube (evidenced by the tube inching away), the bird rolls the bottom up with a key à la a sardine can to force him out. The tube inflates and swells to convey the pressure being applied—the typography on the labeling thusly warps, allowing the growing impact to feel twice as potent. Especially when the toothpaste tube seems to convulse just before the worm is expelled; it very much could have been an error, but comes off as like a rumbling volcano seconds away from erupting. All very clever touches related to something as domestic and inconsequential as a toothpaste tube.

Freleng does get a little trigger happy in his cutting, as a shot of the worm landing in a nearby gramophone seems to cut away to a wide shot almost immediately. Keeping the gramophone visible in both shots allows the audience to piece the action together, but there could stand to be an added beat or two after the worm falls in to give him more focus. Such quick transitions make it difficult to deduce who or what should hold the audience’s attention.

More deductive reasoning from the bird, who brags about how he’s finally got the worm trapped. Never mind that the worm landing in the gramophone was an accident more so than a calculated scheme of the crow’s.

“Now whaddaya gonna do?”

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment