Release Date: April 26th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Dick Bickenbach

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Wolf, Judge, Defense, Bird), Sara Berner (Little Red Riding Hood, Grandma)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Tex Avery’s influence on his coworkers has been a topic of these reviews that has relatively dwindled within the past few years (save for the shorts he directed himself.) It’s not as though his influence wasn’t felt coursing through the veins of the studio after a certain point. Rather, it’s just a given; it’s been well established that Avery steered the studio—and animation as a whole—on the path that it now follows. Likewise, the neighboring directors have been stepping comfortably into their own cinematographic identities and dictating their own unique perspectives. Thus, the line of what Avery influenced and what didn’t begins to blur. It’s not a guessing game.

With all of that in mind, his influence does bear repeating for the coverage of The Trial of Mr. Wolf. Through the violent subversion of a fairytale to the Katherine Hepburn impressions, from anarchic grannies to brazen neon signage overcompensating in providing directions, all of the above are firmly rooted in Avery’s sense of humor established by many of his past cartoons. It is very much a love letter to all that Avery has established, while maintaining Freleng’s own personal taste, commentary, and vision. Considering that they were two of the funniest directors at the studio as of this cartoon’s release, that proves to be a bonus.Indeed, such is the first of many fairytale parodies from Freleng. He revered his fairytale cartoons almost as much—if not even moreso—than Avery, and that applied especially for the Big Bad Wolf. Whether as a convict in front of a jury, an illiterate Deems Taylor type, a jitterbug who can’t seem to catch a break, a pitiful trumpet player zealous to start his professional musical career, or a henpecked husband, the wolf served as putty in Freleng’s hand to experiment, subvert, and stretch the boundaries of a fairytale cartoon for years to come. It’s this very short that kicks off such a phenomenon.

Its plot is exactly as the title implies… almost. Mr. Big Bad is on trial against Red Riding Hood, where he is finally given the opportunity to retell his version of the story—one that joyously luxuriates in its disingenuousness.

A brief technical note before delving into the meat of the cartoon itself: the introduction of this short is the first surviving copy with the new 1941-1945 Merrie Melodies opening theme music (and ‘41-‘55 ending music for the sake of technicalities). Technically, Toy Trouble was the first to receive that honor, yet the inconvenience of a Blue Ribbon reissue shed its titles and awareness. There’s a certain irony given that the Blue Ribbon theme music is taken from the ‘41-‘45 intro.

Even as early as the opening, Avery’s influence can be sensed through the brevity of Freleng’s timing. No elongated exposition of any kind—just a shot of the judge (an owl, of course, symbolizing wisdom and justice), the clearly not-so-innocent wolf in his hip three piece suit and cap, and the jury clearly demonstrating their bias. Freleng throws pieces of information at the audience in small bursts to the point of almost feeling discombobulated. There doesn’t seem to be like a tangible connective tissue stringing the ideas together, even though they’re clearly all related and coherent. It’s clear that the “why” and “how” of the trial are more important than the “what”.

In spite of the almost disarming quickness, the vignettes still offer plenty to absorb and enjoy. Disingenuousness oozes from the wolf as he assumes a most pious position, glowing halo a complete farce; then again, his method is somewhat effective, as the drawings of the wolf are rife with appeal and charisma. Freleng opting to open with him and not, say, Red, demonstrates his eagerness to explore the wolf and the priority he holds in the cartoon.

Elsewhere, a skunk is visibly segregated within the jury. Given the prevalence of the skunk as a plot point in Avery’s Porky’s Preview, the inclusion of a skunk could also be interpreted as an Avery leftover. Most amusing, however, is not the separation between the identical wolf cheering section and the skunk. Instead, it’s the detail of the open window behind the skunk; the curtains flap in the breeze, armed with the implication that the skunk’s fumes need to be aired out of the room. Such a tiny, seemingly inconsequential detail (especially for such a short amount of time on screen) implies a story behind it, which, in turn, renders the cartoon more structurally sound and rich through such details. The gag is a set piece rather than a forefront of focus, making it easy to miss—however, those who catch it feel vindicated that they did.

To accommodate his personal entourage of fans, Mr. Big Bad graciously takes a bow. Such a display of warm conceit does no favors in painting him as innocent.

Nor do the assortment of weapons that conveniently slip out of his coat pocket.

To have all guns or all knives would be one thing; such a variety instead makes the composition feel more “busy” by offering more details to ingest. That, in turn, makes it seem as though the wolf possesses more weapons than he really does, encouraging a stronger sense of violence. The elongated eye take that follows (in tandem with his scramble to round up his paraphernalia, touting many amusing multiples and smears) doesn’t do much to further clench his integrity. Such a frantic reaction indicates guilt. If not guilt, at the very least awareness.

Ditto for the wink that follows.

Focus therefore shifts towards Red. Already, just from the way she looks, the audience expects her to speak in the stylings of Katherine Hepburn. They would be correct. Between her gentility, her face made up, and her grandstanding of “I’m innocent—rah-ly, I am,”, she serves as a far cry from the shrill, pubescent alternative in Freleng’s masterpiece Little Red Riding Rabbit.

Cheering sections quickly devolve into a jeering section as a cacophony of boos emanate from the wolves. At the risk of creating a slight dissonance between the motion/lip sync on screen and the audio, utilizing a stock soundtrack of jeers (rather than multiple recordings of Mel Blanc sandwiched on top of each other) produces a funnier end result through its ferocity. While the disdain towards Red is earnest, the delivery of their contempt is just as disingenuous as the wolf up in the stand. Freleng is a better director for it.

Rowdiness of the crowd is accentuated through the judge’s robes. While its main purpose is to get a laugh from the reveal that his robes are boxing robes and not judges robes (thus nulling his authority), it is likewise beneficial in constructing the image of a rowdy, jeering courthouse. Jurors are akin to fans in the crowd, the wolf and Red being the two combatting teams, the judge serving as a referee.

Like the competent referee/judge hybrid he is, he calls upon the defense attorney to present his case.

Said attorney’s argument is simple: there are two sides of every story, and everybody’s heard Red’s schlock time and time again. Now, it’s time to lend an ear to the wolf.

Of course, the manner in which he delivers this sentiment is much more hyper and bombastic. His animation is just as heavy and imposing as Blanc’s vocals, which border on screaming; the design of the attorney remains simple, which offers the animators to channel their artistic identity and give him some individuality.

One thing’s for sure—he’s handled with much more appeal than the background crowd. With the exception of the skunk, who is animated to wave coyly at the attorney as he wanders over amidst his raving, the wolves are all lumpy and vague in their execution. They stare straight at the camera (rather than at the attorney), producing an uncanny, thousand yard stare that makes it seem as though the attorney is yelling into nothingness. Having every single wolf turn his head to match the constant pacing of the attorney would be on the opposite end of the spectrum, but some attempts to angle their faces and bodies—or at least shift their eye level—could greatly benefit a sense of liveliness.

Nevertheless, yelling and raving and filibustering does offer an avenue for further visual gags. A shriek declaring she “has guilt written all over her face!” encourages Freleng and Mike Maltese to take the attorney’s words to heart. Stalling overdoes it with the “plink plink” musical accompaniment caricaturing Red’s bewildered blinks, but the gag is much more innocent than it is not.

Thus, with the support of the courtroom established, the wolf indulges in his story. He is another upholder of the pseudo-Bugs Bunny voice, always a synonym for street smart, tough, shifty characters. Before launching into his spiel, he clings to the last vestiges of his pious act; a very clever attention to detail in maintaining consistency.

“It’s a Sun-dee afternoon, an’ I’m comin’ home from the pool hall—I mean, uh, Sunday school…” It should be noted that the wolf in Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood was also seen lurking around the pool hall. A quick way to communicate the “grittiness” of the character and, in this instance, a lack of innocence.

His saccharine overcorrection of “I’m always goin’ t’ Sunday school” is priceless through its transparency. Nobody is meant to buy it for a second. Even if he hadn’t allowed the slip-up of the pool hall, the audience still would have been able to deduce from his voice, his clothes, and the arsenal in his coat pockets that he’s completely full of bull.

“I’m skippin’ along, fulla da spirit of brot’erly love.”

A dissolve of the camera fully plunges the viewer into his story. Riding on the high of the wolf’s insincerity, his “reality” is constructed to be as coy as humanly possible: meadows peppered with daisies, the wolf tinkers around in a sailor suit (that, from certain angles, almost looks to be too small, again cementing how out of his element his vision is—even his clothes in his imagination reveal that something is amiss) to an equally juvenile accompaniment of “Gavotte”.

In spite of the scene consisting of aimless prancing from the surface level, it serves as a beacon of Freleng’s many talents. Most noticeable is the sharpness of his musical timing; every little movement is always considered musically in any Freleng cartoon (and any Warner cartoon, for that matter), but the instances where characters are actually dancing and intentionally marrying themselves to the music are some of the most impressive. Orchestrations are flighty and fast, which makes the constant synchronization doubly impressive through the quickness in the timing.

Poses are differentiated from one another and various planes within the composition are occupied to maintain visual interest through variety and depth respectively. Likewise, the asininity of the wolf’s poses themselves are, in simplest terms, just plain funny. Freleng’s dry sense of humor lingers over the cartoon, poking fun at the wolf’s falsities that encourages the audience to do the same.

Such is most noticeable when the wolf accidentally kicks himself and flops to the ground. Again, even in his own story, he’s not free of scrutiny; the gesture is almost Freleng and Maltese’s way of telling the wolf to stay humble—just because we’re in his imagination doesn’t mean he’s free of consequences or humility.

The smattering of flowers, likewise, don’t only serve as a backdrop to give the audience cavities through faux saccharinity. Instead, the next sequence depicts the wolf picking flowers for his mudda (“I’m always tinkin’ of me dead old mudda…”), meant to serve as an excessive topper to his disingenuous. Skipping around in sailor suits is cloying. Picking flowers while skipping around in sailor suits, even moreso. This, too, serves as a wonderful opportunity for Freleng to flex his musical timing.

“I’m convoising wit’ Mudda Nay-chuh…”

Only Mudda Nay-chuh doesn’t wish to convoise back. The “little boidie” erupts in a classic, booming Mel Blanc yell; his dismissal of “GO ON, YA JOIK! ACT YA OWN AGE!” again supports the earlier message about the wolf’s imagination not being exempt from keeping him humble or free of ridicule. All sides point against him—even the most insignificant of bit players in a story he fully concocted himself.

Caricature of the bird haughtily flying away is handled intriguingly. Ferocity of his wings flapping is more akin to the buzz of a hummingbird than a regular sparrow or swallow, which conveys a razzing abrasiveness complimented by Stalling’s equally aggressive musical accompaniment. His wings are caricatures purely through airbrushing, with little streaks of dry brush to give density to the action and allow the audience to comprehend it in some way. More and more, as the years slowly progress, the artists are learning how to utilize other means of painting to express speed and exaggeration. The 1940s is when the dry brushing and airbrushing would really hit its peak.

With that out of the way, the camera makes a cross dissolve back to the wolf in the courtroom. Such enables him to give more exposition (“And whaddaya t’ink’s goin’ on behind me back? SAH-BUH-TAHJEE!”) in a way that doesn’t bore the audience. Cutting back to reality reminds the viewers of the stakes at hand, as well as maintains variation in the flow of sequences. Staying glued to his imagination has the potential to get dull—especially in instances where it isn’t necessary. So, brief as this aside may be, it does serve a purpose.

Another cross dissolve back to fantasy introduces Red, saboteur extraordinaire. Freleng and Maltese’s commitment to the reversal of roles is the short’s greatest strength at its core. Indeed, Red is depicted as conniving, sly, sneaky, bearing a grimace and her hands hooked like claws as she sneaks along through the dark forest. Again, the audience knows that this is completely false, as there’s no way she would ever behave like that. Instead of acknowledging as such through a witty aside (even if it was a “This is so silly, don’t you think?” as is the case in Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood), Freleng trusts his audience to distinguish fact from fiction. He lets it as it lies.

Red’s furtive tinkering is, today, easily distinguishable as a Freleng trademark. It’s in practically every Sylvester and Tweety cartoon. Freleng’s wolf has been prone to do it in more literal atmospheres. It’s a hallmark of a cartoon villain; playfully over the top and matched gracefully through Stalling’s pizzicato plucks.

Yet, as of 1941, this was still a relatively new trademark; the only short of Freleng’s to feature it before this one was Porky’s Hired Hand. There is a certain extravagance in Red’s tinkering that is absent in Hand—Hand, likewise, possesses a heavier ambience. Ambience isn’t necessarily the goal here, nor was exaggeration in the former. Nevertheless, Freleng’s devotion to the bit is clear, as is his love for it. Over time, he would perfect the stereotype musically, behaviorally, and—most importantly—comedically.

So, not only is Red a villain, but a villain who acts on her villainous impulses. While her capturing the wolf and eating him would be a bit extreme as far as reversals go, sticking out her leg and tripping him (jaunty, juvenile musical score initially accompanying another great shot of his gay traipsing) is much more believable. At least, much more believable in a story that paints Red as a villain. The sneer on her face as she watches the wolf fall indicates a deliberateness behind her actions, again justifying the wolf’s pretensions of her wretchedness.

“Hmm. A squoit in distress!” is the wolf’s keen observation of the matter. Carl Stalling’s music score is just as disingenuous as Red’s belabored “boo hoo hoo”-ing; whiny, obnoxious, and somewhat discordant, it again serves as Freleng’s directorial voice reminding the audience of the story’s flimsiness. The characters commit to their reversal—and very well—but the environments and filmmaking (the music, the setup, the sailor suit, the conniving glares) offer a constant reminder that this is all a lie.

“I’ve lost my way to Grandmama’s house, rah-lly, I have…” A few more boo-hoos follow for good measure.

There’s such a comedic simplicity in the wolf’s reply of “Rah-lly?”; so much so that Red’s confirmation of an additional “Rah-lly,” almost neuters it. His tone is sincere, inquiring, but Freleng and Maltese completely intend for the gesture to be mocking. Allowing it to sit on its own enables the audience to appreciate the dripping sardonicism in every crevice. Red’s response is funny, adding to that sardonicism, but there is a bluntness and power of independence to having Red potentially ignore his well-intentioned mocking that isn’t fully realized here. At the end of the day, it’s an incredibly minor and meticulous critique; the exchange is still very funny, as is the asininity of the entire scenario.

Ever the gentleman, the wolf kindly offers directions with the aid of his four-in-one compass. Mentions of multiple fairytales as the dial flourishes between each one certainly feel rooted in the crossover aspect of Avery’s shorts (as evidenced most strongly in The Bear’s Tale.) Simple, but amusing; it tells a story through it belonging to the wolf, as though he’s used it to crash the other stories as well.

However, we are still in the wolf’s imagination, and so it it Red who does the crashing as she kidnaps the wolf. An integration of modern inventions again coyly discredits the wolf’s notions; fairytales are timeless, yet old fashioned. Surely all kidnappings occur by hand. Yet, this is a radical case—Red’s motorcycle and sidecar both contribute to her imaginary abrasiveness, concocting the image of a rough-and-tumble firecracker rather than innocent little girl, as well as incorporate modern elements for the sake of further subversion.

Timing of the animation proves hypnotic. As they roar along, the wolf repeatedly ducks into his sidecar as trees suddenly pop into view. Establishing a solid rhythm of take, duck, cautiously rise up and so on, Freleng banks on the viewer to get lost in the circuitous smoothness to have the wolf actually get walloped at the last minute. Granted the setup of the wolf ducking from tree branches, the inevitable is, well, inevitable. Yet, instead of obeying the rule of threes like most directors would, Freleng stretches out the bit somewhat further to capitalize on the hypnotism of the rhythm and catch the audience off guard at the last second.

Excessive signage pointing to Grandma’s house again asserts itself as another fond takeaway from Avery—particularly the brazen neon signs blinking right on her house. Here, however, the neon signs live up to their advertising nature; “FURS” in bright red hints that Granny, like Red, has her own nefarious intentions with the wolf.

A close-up shot of the house’s façade clinches such a notion.

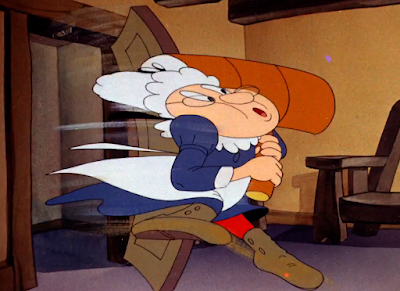

Enter Granny, whose appearance isn’t far removed from Elmer Fudd’s in his coming Freleng appearances. Maintaining the overarching theme of antithetical behaviors, she doesn’t lie patiently in her bed, twiddling her thumbs to await either Red or the wolf. Instead, she dances to her record, wolf furs prominently in the background as she thrusts her rear and scandalously shows us her stockings. A carefree, youthful—if not eccentric—personality that establishes itself to be just as off-kilter as everyone (and everything) else.

A sign and buzzer suddenly alert her to the wolf (again rooted in the Avery philosophy), indicating that she’s well equipped with her process. She proves herself to be much more crafty and alert than the wolf, by his flimsy admission.

Thus, restoring everything back to the norm offers another opportunity for Freleng to flex his musical muscles. Matching her struggle to remove the needle off of the record, Granny collects and stows her furs in silence—somewhat. Poignant woodblock strikes accompany her every movement; scrambling from each fur, grabbing it, putting it in her arms, and rushing to the next one. The sound effects are the forefront and almost feel completely manufactured—such instills an infectious sense of mischief. It’s a maneuver that, for lack of a more educated term, reminds the audience of the cartooniness of the situation. Pure caricature for a scenario that itself is caricature.

Cal Dalton animates Granny beckoning the wolf in: a chorus of Sara Berner crying out in pain and sprinkled with a few “Gosh, it hurts”ses. A warmer welcome could not be had.

“She has a terrific hangover—oh, I mean, ah… she’s very, very ill….” is Red’s justification of the moans. Walking Hood as well had its sly bout of “alcohol humor” with the equally eccentric granny in that one slyly ordering a case of gin from her grocer. Hangovers insinuate alcohol, which often insinuates partying, again shedding light onto how much of a loose cannon this granny really is.

After shoving the wolf in too “cheer her up”, Red locks the abode through the courtesy of multiple different doors. While it isn’t a uniquely Avery trait, seeing as other directors would have done something similar beforehand (such as Bob Clampett in Porky in Egypt), it does prove difficult not to associate Avery with the gag—particularly in something like Northwest Hounded Police. Granted, that cartoon was made five years after this one. Such is more of an example of how far Avery’s influence is spread and adopted, rather than making the argument that Freleng—or anyone, for that matter—was ripping him off. This is still very much Freleng’s cartoon.

Wasting no time, Granny and the wolf jump right into the routine (with Granny now touting the benefit of hair.) The wolf’s answers are strong in maintaining his pious disingenuousness—for example, comments on his big eyes are dismissed with a “Da bettah t’ obsoive da wondahs of Mudda Naychuh wit, Gran’ma!” His commitment to the bit is truly impressive.

Likewise, Granny is committed to her own bit of selling wolf furs. “My, what a beautiful fur coat ya have!” is followed with an aside rooted in more truthful intentions: “Should bring about 35 bucks…”

After another bout of false modesty, the wolf soon finds himself repeating after Granny: “My, what a big mallet you got, gran’ma!”

“All the better to get a new fur coat!”

Thus, the gratuitous chase scene ensues. Thankfully, only the first establishing pan of the chase seems obligatory, mainly due to a dissonance between intentions and reality. Both the wolf and grandma are intended to be rushing around at Mach speeds, able to gain traction by running on the walls. Blurred backgrounds and race-car sound effects do a fine job of informing and caricaturing their speed. However, the actual timing and spacing of the animation itself—while solid—remains very literal and not entirely indicative of the intended exaggeration. Both the speed of the timing and the camera pan could stand to be quicker.

Such is rectified through the following sequence. A number of smears and visual distortions litter the scene, which is certainly helpful in conveying the ferocity of the speed (especially as of 1941, where the potential of such distortions was still being realized.) However, much of the heavy lifting is in Freleng’s mechanical timing. Both the wolf and the grandma operate at very stop-and-start speeds, operating in short, stilted bursts as they go in and out the door. Fragmented musical timing and sound effects do wonders in accentuating such meticulously choppiness; in spite of the action momentarily coming to a halt every second or so, the display and handle of speed is much more convincing.

With the idea that Granny is antagonistic towards the wolf established, Freleng shifts priorities to a climax of gags and action rather than just chasing. That is, with each wolf the door opens, he is met with an increasingly more aggressive Granny. Threats of a knife meld to the threat of a machine gun, which then transforms into the threat of an entire cannon. Incredibly well timed, the momentum is palpable and the climax is genuine in its increasing intensity. Frank Tashlin would do the same nearly verbatim in Plane Daffy with even sharper timing. Genuinely funny, genuinely captivating, and another wonderful pit in the wolf’s story—would any member of a jury truly buy that the granny just had some heavy artillery lying around?

Riding off of the momentum and quick slew of ideas, Freleng enables a pause as the wolf opens the door to Mudda Naychuh. No guns, no knives, no cannons; such quietude and absence of an armory is almost too good to be true.

It is.

If bashing the wolf over the head with a hammer and knocking him out isn’t enough, Granny firmly establishes her intentions to kill by jostling and choking the wolf. In spite of the story’s absurdity—which is plentiful—it is certainly much more violent than the actual fairytale. Devouring someone in the flesh is cruel, but a much quicker death than asphyxiation. Especially asphyxiation that follows numerous attempts of assault. If the wolf were telling the truth, he would have quite a case on his record.

Speaking of his case, the camera dissolves back to the courtroom, where the wolf is strangling himself in his chair to finish off his story. If the “flashback” sequences were absurd, one can only imagine the theatrics and histrionics presented in front of the jury as the wolf acts it all out. Having the wolf choke himself serves as a coherent jumping off point to segue back into reality, but also hints at that sort of backstory, prodding the audience to imagine that he’s been acting it out the whole time. Menial of a detail as it may be to comment upon, it makes the cartoon just a bit more rich as a result.

“An’ it was only t’rough a miracle that I escaped wit’ me life,” concludes a winded, slighted wolf. Dick Bickenbach serves as his assigned animator for the remainder of the cartoon, drawings and acting full of appeal and believability. It should be noted, of course, that the wolf doesn’t elaborate on how he escaped—that’s not necessary nor helpful in slandering the name of Red and her grandma.

In a surprise twist, his jury bear not grins or expressions of support, but grimaces of suspicion and disdain. Given their support in the beginning (and the fact that they are all carbon copies of one another), the audience is led to believe that they’d support the wolf’s duplicity no matter what. To have them display such suspicion—which is certainly justified—feels like a genuine betrayal.

Mr. Big Bad is sharp enough to sense such debauchery, growing indignant.

“An’ if dat ain’t the truth, I hope…” He stalls, indicating a lack of confidence, no matter how subconscious, “I hope I get run over by a streetcah!”

His wish is Freleng’s command, whose timing of the collision is excellent. As has been stressed in previous reviews, talks of Freleng’s timing often immediately differ to his musicality. After all, he was a classically trained violinist, and his musical timing is the easiest to place a finger on. Yet, such praises are also directed towards his comedic timing and behavioral timing. He is responsible for some of the most well timed explosions and impacts and streetcar collisions out of all of the directors; this scene is just one of many examples of his talents.

Enough time is allotted for the audience to soak in the gravity of his words. Said words are an invitation, so the punchline is somewhat expected; yet, it’s the timing that is so pivotal in getting a laugh. A beat allows the audience to revel in his words and assess the situation, but not enough to completely expect the ear splitting crash that follows. Timing the impact on ones enables a freneticism important in embracing the spontaneity and intensity of the action.

Really, the action of the streetcar bowling over the wolf speaks for itself, and Freleng could have ended the cartoon there if he wanted to. Instead, he treats the audience to the relief of justice: the wolf fessing up that he potentially exaggerated—not lied—and only “a little bit”. The audience has known this the entire time, but it is still satisfying to get his omission in writing.

For the true beginner of his unofficial “fairytale series”, The Trial of Mr. Wolf is an incredibly promising start. It is easily one of his funniest shorts to date; not that the humor in his shorts is impossible to decipher, but Freleng was a master of subtlety to a degree that many often miss some of his intentions. The humor is a bit more obtuse in this one, but not out of patronization or excessiveness. Its joke density is clear.

Freleng and Maltese’s experience on The Cat’s Tale—talky as it is—seemed to be helpful in guiding the criteria of this cartoon. Both shorts share a common theme: subverting a common trope and getting to witness the other side of the argument. While this short is also dense in dialogue, there are plenty of visual gags and laden pauses to construct their own commentaries. Moreover, the dialogue is bright, funny, and fitting. No noise for the sake of making noise.

Inspiration within the cartoon isn’t solely reliant on Freleng’s direction or Maltese’s writing, of course. The animators continue to display their constant artistic evolution; there lies a particularly poignant plethora of multiples, smears, and distortions in this cartoon—not to the effect of The Dover Boys, but that’s its own league entirely. Indeed, learning to embrace these techniques proves helpful in embracing the reigning freneticism and mischief of this cartoon. It’s a fast paced, zany cartoon dealing with caricature in all aspects and the animation is certainly able to convey that. Personality animation is strong in the slower, expositional portions, and a sense of urgency is keenly conveyed through more pressing climaxes.As he would evolve, Freleng would place similar spins on similar fairytales to a greater effect. It is still relatively early in his career. While his 1941 shorts have certainly been establishing themselves as good (in the most minimalist of terms!), it’s far from his peak, and that applies to this cartoon. A great cartoon indeed and especially successful within its time, but perhaps its greatest contribution is serving as a proud stepping stone and allowing Freleng to realize just what he could really accomplish. If he can do this, then he can do Pigs in a Polka, or Little Red Riding Rabbit, or Three Little Bops, and so on and so forth.

In any case, this is a very spirited cartoon and a very funny one. Easily a highlight of his directorial career—an’ if dat ain’t da truth, I hope I get run over by a streetcar.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment