Disclaimer: This reviews racist content and imagery for the purpose of historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up and let me know in the case I say something that is harmful, ignorant, or perpetuating, so that I can take the appropriate accountability and correct myself. Thank you.

Release Date: May 10th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Rudy Larriva

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky)

(You may view the cartoon here.)

Barring a somewhat extended cameo appearance in Toy Trouble, Porky’s Ant heralds the second time Porky Pig has been within Chuck Jones’ hands. He, too, would prove to be instrumental in handling the development of the character—with the aid of Mike Maltese’s writing expertise, the two would fashion him into a role of maturity. It proves difficult to remove Porky of his naïveté, which thankfully Jones didn’t do, but his motivations and roles would be considerably more adult. Especially in the shorts where he established himself as the all-knowing, smarmy but good humored foil to an impulsive, raucous Daffy.

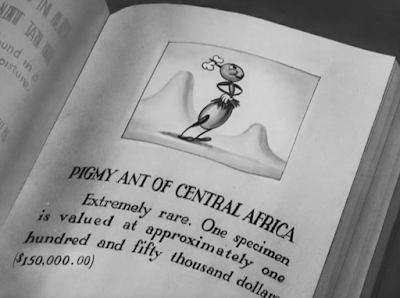

Jones’ shift to maturity for the character is amusing, considering his roots; while Porky isn’t a child as he was in the last Jones short, Old Glory, he still may as well be one. Decidedly baby-faced, innocent, mainly communicating through grins and frowns and empty stares, that endearing juvenility remains a prime focus.A concept that would be refined to a more palatable degree in Porky’s Midnight Matinee, the cartoon follows Porky as he once again finds himself back on an African expedition. This time, searching for an elusive African pygmy ant worth $150,000. As luck would have it, he finds his pot of gold—but said pot of gold doesn’t wish to be found.

Limitations of a black and white color scheme don’t prove to be bothersome for Jones’ art direction. Joe Glow, the Firefly is yet another gorgeous black and white cartoon, though the consistent nighttime setting doesn’t allow his painters to experiment with a wide array of values. Such is more apparent in this short, and the opening shot especially—white palm trees and leaves mingle with dark, twisting branches, details in the backgrounds a milky amalgam that enables the eye to travel to Porky with ease. Likewise with the branches in the foreground creating a subtle frame around the action.

Similar comments apply as the camera trucks in to reveal a somewhat more intimate look at our traveler. Brush and vegetation obscure the view of the audience; environments feel more believable in their denseness, refusing to make a sacrifice for the convenience of audience clarity. It moreover instills an innate prick of mystery. Taking such liberties to obscure Porky must come with a reason.

Comedy is always the reason. A particularly imposing tree serves as the perfect bridge between visuals—Porky comes out from the other side, completely missing his tower of supplies. Jones seeks to evoke curiosity from the viewers, second guessing what they just saw or didn’t see.

Rest assured, his supplies are still in-tact: just revealed to be transported by Porky’s woefully designed companion. All things considered, it is a cleverly executed reveal. No hints of any kind give anything away that the materials aren’t strapped to Porky’s back. It’s a polite subversion, and certainly par for Jones’ tastes, but succeeds in its mission of prompting doubt and surprise from the audience.

While the egregiousness of the boy’s design doesn’t need to be spelled out, it is worth taking a look at the evolution of Jones’ designs within the past few years. Here, the boy boasts a much starker degree of caricature than Inki in The Little Lion Hunter. Inki’s own design is unfortunate, but comparatively conservative when looking at the design here. For one thing, his lips don’t dominate the entirety of his jaw.

It is not my place to speculate or “justify” these sorts of design decisions—at the end of the day, regardless of intentions good or bad, they remain harmful. Yet, given Jones’ discomfort in working with such material (such as denying his involvement on the particularly abhorrent Angel Puss), it seems that a part of the caricature being so extreme here is mainly based out of a desire to streamline. Indeed, the lushness of Jones’ characters has slowly grown more sleek, caricatured, simplified over the years. While still a far cry from the snappiness of his art direction in later years, one can see his attempts to learn and grow and refine. That entails exaggerating certain features, experimenting with weight distribution, trying to make designs more funny and less literal.

Obviously, the design of the boy here isn’t funny, but certain decisions with his design to seem to be a side effect of Jones’ continued refinements rather than a separate case rooted purely in malice. Again, regardless of intentions, racism is an unfortunate and overwhelming consequence, but it does prove to be intriguing trying to get into Jones’ line of thinking.

In any case, the camera takes a turn to shed light on Porky and introduce the audience to further expedition. Both the outside cover and inside contents of his book clue the viewer that he’s set out to hunt for some rare insects. In particular, the African pygmy ant who, likewise, boasts a rather unfortunate design under the guise of cuteness. As mentioned in the introduction, he would return and be a central player in the companion piece to this short, Porky’s Midnight Matinee.

Porky expresses his desires to catch such an ant, “boy oh boy”s and all. The pause as he grins towards the camera is awkward and unfortunately deflating more than endearing; it’s a gesture that serves as a coy acknowledgment, which is fine in itself—not so much if the action justifying it isn’t necessarily funny enough to warrant the pause. He just stumbles on a word and switches it for another, as is usually the case. It’s stilted, but this was Jones’ second outing with the character. His indulgence is understandable.

Nevertheless, Jones’ art direction—egregiousness of racist character design tropes notwithstanding—proves difficult to argue with. Backgrounds often airbrushed to offer a hazy, foggy atmosphere, which both instills an elusive sense of adventures and giving more depth to the surroundings. Contrasted against the crisp, opaque density of the grass in the foreground, the effect is rightfully striking.

Likewise with the footsteps sweeping past the screen. Each character is armed with a slightly differing musical accompaniment; Porky’s motif is somewhat more imposing and deep, given he’s the largest (in spite of his diminutive stature.) The boy’s motif is more mischievous, light, a circuitous sliding rhythm to match the movements of him shuffling forward.

Airy piano glissandos conjoin with the introduction of a new silhouette on screen. A bone in its “hair” and geometric construction hints at it being just the ant Porky is looking for. Its silhouette is handled incredibly well—very clear in its construction, as well as its emotions. The smile that creeps on its face is slight, but offers enough of a gap within the silhouette of its face for the audience to catch and appreciate.

So, ever courageous, the little ant pursues the caravan. Such is a very Jones thing to do; rather than recognizing the threat of potential hunters, the little ant is portrayed as naïve, cute, innocent—he wants to play along. Interest in the ant from the audience isn’t from following the ways in which he hides or protects himself from being hunted. Rather, it is more sympathetic and simultaneous: indulge in what he wants and why.

As revealed through a dramatic up angle and glowing effects, the object of his desires is the bone in the boy’s hair. A return to Jones’ roots, whether it be a Curious Puppies short from 1939 or his animation of a dog pursuing a bone in Bob Clampett’s Get Rich Quick Porky. Jones seemed to absolutely love his bones.

Cue a belabored scene of the ant comparing his diminutive bone to the giant one right in front of him. Again, to the credit of both Jones and his animators, the pantomime is exceedingly clear. Through the ant’s gestures—feeling his own bone, comparing the gap, then trying to surmise the length of the boy’s bone—his motivations plainly tell is that he wants that bone. Communication is key, and achieved well, but the pacing is sluggish and not particularly endearing.

A bright spot does stem from the ant analyzing the length of his outstretched arms; his head jerks from side to side with few inbetweens or follow through, injecting a refreshing bout of snappiness that is much appreciated against the lugubriousness of the vignette. Likewise, the drawings are relatively appealing and, again, communicate all they need. Just woefully slow.

Innocence of the creature is again embraced and capitalized upon as the ant has enough gall to tug on the boy’s skirt. It demonstrates he’s unaware of the ambitions of the expedition, oblivious to his role as a target. His impressionability is endearing, and again a Jones trademark that was a recurring trait of his characters for so much of his early years.

As is a warped sense of scale. Joe Glow and Toy Trouble were two consecutive Jones efforts that allowed him to really revel in one of his pet tropes—character and ambition is a stronger focus in this effort, but there comes bursts of artistic ingenuity that remind the audience of Jones’ affection for inventive, immersive layouts. Particularly the point of view shot of the boy looking down at the smiling ant clinging to his skirt like a lost toddler.

Transitioning to Porky admiring a plant feels a bit jarring and sudden in comparison. Part of that stems from intention—the boy, distracted with his focus on the ant, collides into Porky, prompting their supplies to explode and rain down on each of them in a disarrayed pile. Surprise is a key factor in selling the suddenness of the collision, but it takes an added second or two for the audience to gather their surroundings. Porky seems to vanish and suddenly reappear without warning.

A very minuscule side note; keen eyes will note Porky pushing the brim of his hat out of his eyes as he examines the plant. The gesture makes him seem more youthful and innocent, as though he hasn’t properly grown into his role as an explorer in both a physical and metaphorical sense.

Namely, such a menial acting choice deserves note considering that was a pet acting choice of Jones’ for many of his earliest cartoons. The Night Watchman, his debut cartoon, features Tommy Cat occasionally battling with the all encompassing largeness of his hat for the same factors listed above. This short feels regressive in many ways, revisiting some of Jones’ earliest habits and tropes—some are much more noticeable (such as the ant’s lust for a bone), whereas others such as this one, while seemingly insignificant, still support the idea in different ways.

Regarding the mechanics of the collision itself, they are indeed mechanical. Objects seem to pile on each other harmoniously, in order. There isn’t necessarily a sense of weighted spontaneity to inflate the impact of the crash or a sense of surprise. Objects retain their solidity, which is arguably one of the most important aspects to sell the tangent, but the motion and spacing of the drawings themselves feel mechanical and perfect. Uncanniness presides over humor.

More hat fiddling ensues from Porky as he unearths himself from the rubble, more visible this time to allow the audience to revel in his diminutiveness. A slight cel error prompts a piece of supplies to flicker on and off the screen, but the illusion of weight as he shifts the boxes out of the way is convincing.

A bookend to the earlier “aerial” shot of the ant is ushered in, this time from Porky’s point of view. Jones’ conscientiousness and an eye for detail pays off—rather than having the layout be constructed at a 90° angle, as was the boy’s perspective, the angle is more relaxed here. Still dynamic and exaggerated, but with enough of an ease to account for Porky’s placement further away from the ant.

Furious digging to unearth his bug book follows. Animation is approached with a bounciness that conveys playfulness over urgency, which proves to be a more fitting outcome. It’s a smiling, friendly ant—not a bear. Slight smears and distortions on Porky’s legs as he kicks aids in selling his zeal. Bounces as he settles into position do the same to an effect of stronger innocence and naïveté.

Consulting the bug book isn’t for means of identification. Instead, it’s to get confirmation on the price value. Jones utilized a shining perimeter around the boy’s bone to caricature and demonstrate the desires of the ant—now, that same effect encases the price tag of $150,000 to illustrate Porky’s desires.

“A hundred an' fifty thousand duh-dih-doll-ehh-duh-dih-ehh—bucks.” Voice direction for Porky is underplayed, which is always nice. Going too bombastic, too performative—especially with a more grounded character such as Porky—can risk sounding disingenuous if the story or context doesn’t call for it in that moment. His ability to harness that organicism in vocal deliveries is a skill, as embracing and depicting the naturalism of it can be a finicky struggle.

However, the line could benefit from some exaggeration; even if that manifests in an exaggerated sense of hushed awe. Jones reprises the bit in Midnight Matinee to further success—Porky’s stuttering is more profuse, which is a symptom of accounting for the specificity of the price tag: $162,422,503.51 (plus sales tax). His deliveries are more urgent, but still clinging to a subtle, restrained shock. A “Yee-yee-ye-yipe!” is likewise glued to the end for good measure. Only one of many examples of Jones ironing out the kinks established in this cartoon, and to comfortable success.

Only now does the ant realize he’s a target instead of a friend. Thus, the main idea of the cartoon is kicked off through his frantic speeding off-screen: an elaborate chase to nab a prize.

Given that a little more than five minutes of runtime remain, the chase is fragmented, thereby not essentially feeling like a tried and true chase cartoon. Thanks to the often circuitous nature of chase cartoons, that isn’t exactly a bad thing. However, there certainly are some sequences that could stand to be halved in their run-time.

The ant diving into a hole and popping out from an adjacent hiding spot as Porky fails to capture his prize, for one thing. Running up the side of the hole takes too long, Porky rooting around within the hole could stand to shed a second or two, and the lugubriousness in which he spots the ant, swipes for it, slowly opens his empty hand, and spots the ant waving at him also takes too long. Jones embraces the slow burn to allow the audience to stew in the thoughts and emotions of the characters—considerate, but maybe not the most necessary priority at the time being. Regardless, the animation is solid and charming, and the leaves casting a frame over the ant as he attempts to scale the first anthill is a clever and thoughtful artistic decision.

A lure is thereby in order to entice the ant. Ever conveniently, Porky just so happens to have a box of chocolates among his supplies—truly essential for braving the wilderness. The reveal of the chocolate box is a bit sudden, seeming to come out of nowhere; it boasts a proper hook-up, with the scene before entailing Porky rushing back to his supplies and digging for materials, but the staging is somewhat unbalanced and obscures most of the view of Porky. We don’t even see the box in the previous scene, which is why it comes as such a jolt in the cut to a close-up. A minor inconsistency that isn’t as much of a deal breaker as it sounds, but still notable regarding the flow of consciousness and the audience’s ability to digest the action.

Employing the use of flypaper is much more subtle, with it dragging along the screen as Porky is implied to have grabbed it.

Characters getting stuck to flypaper is one of the oldest tricks in the animation book—Norm Ferugson’s animation in 1934’s Playful Pluto particularly comes to mind, where (as one would guess) Pluto fights with a particularly stubborn sheet of flypaper. Domestic and middling as it may sound now, it was a highly lauded sequence at its time and a part of what distinguishes Fergy as the Pluto expert. Jones’ Curious Puppies shorts in particular are a direct consequence of shorts such as Playful, where the personalities of the characters are expounded upon through their endearingly—though not to all—domestic struggles. Thus, it doesn’t seem to be a stretch in deducing that the use of flypaper here is a direct homage to the aforementioned Disney short.

Even then, Jones understood that the audience understood the gag. Character gets stuck, laborious sequence of glares and glances and various other limbs getting stuck ensues. That is why, following a somewhat bloated return to the ant as he peeks out of the hole and makes a return (with some clever pantomiming using his bone as an emotional indicator), he obeys a more subversive and unexpected route instead:

Zipping around the perimeter of the paper to grab the chocolate instead. Its promptness elicits a genuine sense of surprise and amusement, as there are no belabored reactions following the ant thinking on how to get his prize. It is spontaneous, yet calculated. Likewise, the layout is staged so that the flypaper is close to dipping off-screen into the foreground. Barely any ground is revealed, tricking the audience into thinking that the ant won’t travel that area since it isn’t “clearly” staged. For what it is, the gag is refreshing in its defiance against cartoon stereotypes. Even if one gets the sense that the stereotype is used out of love and respect rather than complete scapegoating.

In fact, it almost comes as a shock that the flypaper doesn’t get stuck to Porky as he grasps it in a rage. That would impede the fancifulness of Jones’ directing as the paper instead waves right into the lens of the camera. It immerses the audience into the cartoon, as though they themselves are a victim of Porky’s polite wrath, it establishes depth within the composition, and, most importantly, offers a transition to the next scene.

For flypaper to go unused would be criminal, even in a short that kindly lampoons its predictability. Thus, the sheet is destined to get stuck on the face of the boy instead, who only just now managed to unearth himself from the pile of supplies.

Further Jones indulgences ensue: the slow pauses, the sluggish reaching for the ends of the paper and being unable to tear it off, the aggravated frenzy of action that follows as the boy turns into a whirlwind in attempting to free himself. His disgruntled expression as he does manage to peel it off is solid and well drawn, informed, and the pantomime is very clear, even with facial expressions obscured. It’s a bout of directorial self indulgence, no doubt, but fits within Jones’ tone and succeeds in what he wishes to convey.

No comments:

Post a Comment