Release Date: February 18th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Norm McCabe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Flat Foot Flookie, Boss), Billy Bletcher (Boss)

The whimsical nature of rubber hose cartoons and their elastic, anything can happen principles meets the solidity and awareness of the modern 1939 cartoonist’s outlook to combine for one of Clampett’s most whimsical cartoons of this period: Porky’s Tire Trouble.

While I've touched on the issue a bit in the past, a large part of my fascination of Porky Pig 101 borrowing this short's opening music and using it on so many unrelated cartoon titles comes from the fact that the title music is so exclusive to this short. Animated by Bobe Cannon (as noted by his rather dopey, prominent buck teeth), Porky's "starring" title card has the privilege of animation. In conjunction with his waving to the audience, a triumphant musical fanfare plays in the background to accompany the movement. As such, using this short's title music, one instance where the music is exclusive to the titles on-screen, it comes as even more fascinating when put on top of titles that don't necessitate a fanfare. As I've said before, it's a very moot point and not the fault of the original hands at play, but it's so fascinating for this very reason.

The opening accompaniment of "Mary Had a Little Lamb" (as well as the title card music of "Monday Morning" and much of the remaining cartoon's soundtrack) was, interestingly, use as musical accompaniment in the 1938 Termite Terrace gag reel, providing some insight as to where this cartoon was in production in late 1938.

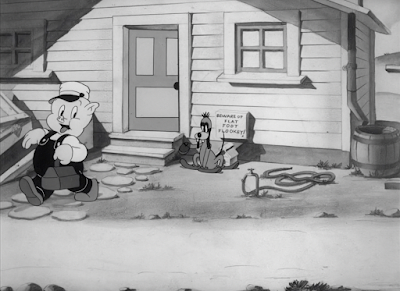

Here, we open to a still shot of a very small doghouse nestled by the front porch. A sign above the doghouse warns any passersby to "BEWARE OF FLAT FOOT FLOOKEY!", the pup's name a reference to the popular 1938 jazz song "Flat Foot Floogie". A long pause allows the audience to brace for whatever hellish fiend resides in the pint-size domicile.

Enter hellish fiend.

Though the size disparity between doghouse and dog is amusing enough as is, the real crux of the juxtaposition lies in Flookey's appearance; decidedly derivative of Clampett's design sensibilities, Flookey is about every single antithesis to "beware" as one can imagine. The long, pronounced shoes on each flat foot certainly sell this. For that and that alone, Flat Foot Flookey is my personal favorite of Porky's many, many, many dogs.

His introduction is nonsensical verging on almost confusing as Clampett is eager to dive into the wacky antics out the gate--something that would sometimes land him in trouble. Here, Flookey growls and bites his rump, wrestling with a flea.

With dainty shoe-hands, Flookey plucks the intruder free from his hide and displays it to the audience. The flea is no flea, but rather, an ant. And, rather than growling at the ant for making him itchy, Flookey and the ant both grin vacantly.

For the record, as much as I lament about Porky not given more mileage during this era of cartoons, I am not at all against the cute, smiley, if not mindless pig. In fact, I love Clampett's oblivious, naïve and optimistic Porky. There's something very refreshing about his innocence, especially compared to the long-suffering straight man he'd become in later years--even if his straight man status serves him the most favors.

A rather surprising amount of attention to detail is paid in the backgrounds, particularly on the posters adorning the fence that Porky struts past. Included on an ice follies poster is even an ad for Looney Tunes.

As Porky continues to head on, his mindless happiness and oblivion is caricatured as he halts his trek to do a very spontaneous dance—perfect for Flat Foot Flookey to imitate as he approaches from behind. The staging is rather similar to the scene of Daffy stalking Porky with the mallet in The Daffy Doc, albeit with much less murderous intent.

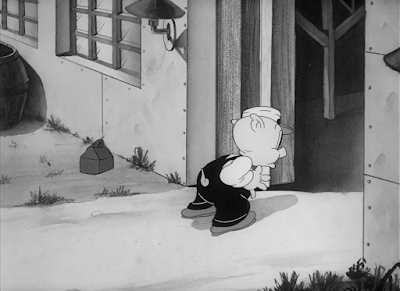

Upon a wide shot of Porky and Flookey heading to work, clearly indicated as “Snappy Rubber Company”, the camera trucks into a smaller sign above the doorway. Miraculously, the camera movement is rather smooth with very few shudders, any significant jolts stemming from a deliberate rise in speed.

The jolt prepares the audience for the jump cut on the “NO DOGS ALLOWED” sign, complete with an apprehensive music sting from Carl Stalling. Even by 1939, audiences were well aware of what to expect from such a tried and true structure. At first glance, the beginning of this short seems to dip its toe in “embracing Disney” territory, which is, at this point in time, a dangerous gamble.

Though the cartoon soon takes a purposeful nosedive out of Disney territory, one can feel Clampett’s appreciation for those cartoons in scenes such as this one. Even if it’s a deliberate set-up to lure the audience into a happy, mundane outing with Porky and his loyal pooch, one feels a genuine endearment from Clampett in his emulation.

Another little going-to-work dance for good measure, mimicked by both Flat Foot Flookey and Carl Stalling’s music score.

On the topic of Stalling, his music score is a force to be reckoned with in this cartoon in particular. Jazzy, energetic, a spring in its step yet homely enough to not feel out of place. It serves as a wonderful accompaniment for Flookey’s antics, particularly when a spritely score of “Mutiny in the Nursery” springs up after he passes Porky into the factory. Rather than walking around him, Flookey slides between Porky’s legs, who halts as he realizes something is afoot. Flat afoot.

It very well could be a throwaway bit of innocent fun, but, knowing Clampett, it wouldn’t be the slightest bit surprising if this was intended to be an innuendo of some kind—especially with the way Porky halts so suddenly, bringing extra attention to the fact that Flookey is sliding beneath his crotch. It's not as though Flookey slid beneath him while he was still walking. Though it sounds especially crude on paper, but Clampett’s humor would certainly evolve to be cruder later on, and Warner Bros is certainly no stranger to the aforementioned gag.

Even then, it takes Porky an extra few seconds to realize what just happened. Clampett was fond of Porky’s delayed reactions, but for good reason—it certainly grounds him and makes him feel more believable, sympathetic, a nice contrast against bonafide screwball types such as Flookey who don’t think as much.

With that, Porky reaches into the depths of the doorway and grabs Flookey by the tail, pulling him out with such ferocity that he’s spent spinning over himself and back on his feet.

Bobe Cannon seems to have been tasked with a majority of Porky’s sequences, instantly recognizable by the erratic head tilts and wide, triangular mouth. Here, he repeats a phrase from Porky’s Badtime Story while tying Flookey’s tail to the bumper of a parked car; “Hey, you eh-cee-eh-cehk-can’t come in here! I’ll lose my juh-jee-jo-eh—I’ll lose my juh-jee-jo-jeh-eh-juh-jehh—I-I’ll get canned!”

Scooping up his lunchbox that got lost in the line of fire when wrestling with Flookey, Porky instructs man’s best friend to stay put. The scene is staged so that both Flookey’s dejected reaction and Porky’s entrance into the factory are clear, the wide shot adding plenty of breathing room.

A slam of the door is marked by a whimsical crash of the symbols, appropriate accompany to the brash music in the background.

Flookey, of course, has other plans. Ever the anarchist, he approaches the entrance of the factory, tail still tied to the car as he begins to dig a hole. The animation is pretty crude, but the crudeness works in its favor—a laborious scene of Flookey trying to dig a hole with his shoe-hands would be monotonous and tiring. The abruptness of his digging adds to the energy of both Flookey and the atmosphere in general, making him seem even more anxious to get inside.

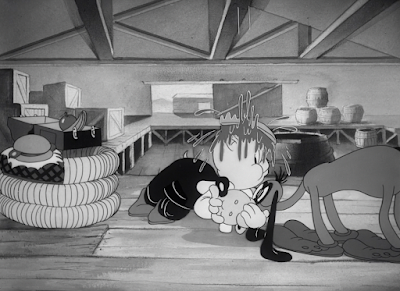

Clampett’s staging takes a rather creative turn as we dissolve to an aerial shot of the factory’s interior. Steal beams adorn the ceiling, and Porky approaching his boss is, even from such a distance, very clear thanks to the deliberate framing of the steel beams and the negative space between them. Such careful attention to figure ground composition seems more akin to Frank Tashlin’s wheelhouse, who understood how to manipulate it best, so to see it employed in a Bob Clampett cartoon—a 1939 Bob Clampett Porky cartoon at that!—is much appreciated.

Truck-in and dissolve to Porky wishing his boss good morning, a hulking walrus in suspenders and overalls. Voiced by Billy Bletcher, his gravelly response of “What’s good about it? GET T’ WORK!” swiftly establishes the relationship between Porky and his boss in seconds flat. The same could possibly be said for the scene in Porky’s Badtime Story where the boss confronts Porky and Gabby for being late—Clampett appeared to enjoy the disconnect between naïve, happy Porky and his grumpy, disillusioned superiors.

Still a score of “Mutiny in the Nursery”, instruments turn from brass to xylophone, the arrangement growing purposefully mechanical as the focus is shifted onto the factory’s inter-workings and the gags therein. A pull of a lever prompts a backhoe to get to work, ceremoniously chuffing out a rhythmic drum cadence found in a number of the cartoons from this era (What Price Porky comes to mind.) The perspective animation of the backhoe turning in the foreground is nice, strong, and solid.

Snappy Rubber Company tires are made by only the most whimsical of means, on par with Clampett’s sense of humor and sensibilities. Taking a giant bite out of a nearby swath of rubber tries, the machinery chews the rubber like a piece of gum, newfound fingers serving purely as a vehicle to play with said gum. Indeed, the animation is incredibly elastic and stretchy, even just the simple act of the machine chewing. The kinetic force is very much felt.

With that, the machine spits the wad of gum rubber onto a giant waffle iron supervised by Porky. The iron closes, and, after a hearty burst of steam, unearths a brand new tire, which Porky dutifully stacks. Judging by the elongated snout and the slow, bloated manner in which Porky blinks, John Carey is responsible for the scene’s animation.

The camera only halts briefly on Porky—as he continues to stack the tires, the camera pans past more tires to focus on the floor near the doorway.

Flookey’s entrance is reflected appropriately in the music with a slow yet anticipatory crescendo, topped off with the all too satisfying “POP!” of a pup breaking work protocols.

After a brief pause to give way to Flookey’s vacant stare, head wobbling around on his spindly neck like a spring, he manages to squeeze himself out of a hole. There’s no build-up of Flookey trying to be discreet here. No tiptoeing through the factory to avoid getting caught, no hide and seek games, no measures to be as quiet as possible. Instead, Flookey immediately makes his presence known not only by barking loudly and happily…

…but dragging the entire car his tail is still tied to in with him. The inconspicuous acknowledgement of the very conspicuous car works to its strength—Flookey only struggles to drag the car that one time. There isn’t a giant hullabaloo about both a dog OR a car infiltrating the factory, no guilt or alarm. In fact, there doesn’t seem to be any thought at all. The mindlessness of Flat Foot Flookey is reflected in the execution of the gag, which is the best way to structure it—obvious objects or things being treated as normal, everyday happenings is where comedy hits hardest.

With that, we head back to Porky on his lunch break (an impromptu one, judging by the way he trepidatiously looks to see if anyones watching.)

A slice of pie is the winner. Both Bobe Cannon and Bob Clampett’s timing is excellent—Porky makes sure to delicately extract the pie from his lunchbox. He winds up to indulge in one big bite…

…when the loyal barking of man’s best friend startles him and causes the pie to be tossed straight in the air off-screen.

Porky scrambles aimlessly in place, trying to get his wits about him before he’s able to clamp Flookey’s mouth shut. A short pause…

And SLAP! Porky’s dessert rains right in his face. The timing and execution are funnier than the gag itself, but is still a winner nonetheless—pausing to cut to a scene of the pie flying in the air would stretch things out much longer than necessary and lessen the abruptness. Here, the unceremonious slap of a pie against one’s skull is what makes the impact so rewarding.

Porky tells Flookey to head out the back eh-duh-dee-doo-eh… beh-back eh-duh-deh-dih-eh—rear exit. Flookey obliges, but not after eating Porky’s lunch, served fresh on top of some ham.

However, the car is still attached to Flookey’s tail. Porky finally gets a dose of his own animal cruelty when the car runs straight over top of him, pinning him to the ground. Flookey, on the other hand, is now free.

Thankfully, Clampett knows better than to make Porky act in pain, which would be a little too uncomfortable—the vacant, pie-covered, mouth agape nonplussed stare is much funnier and conveys all that we need to know. That, of course, paired with the furious honking of the car horn.

Now it’s Flookey’s turn to scold, furiously shushing Porky with his delicate shoe-hands, as if Porky were the perpetrator of the noise.

Flookey’s scowling grin as he heads off to attend his dog-like matters is great. Clampett’s screwball characters simply do, not so much think.

The furtive atmosphere purposefully missing in Flookey’s entrance to the factory is now on display as he cautiously creeps along some wooden beams, marked by Carl Stalling’s soft descending string scale.

Enter the bread and butter of the cartoon. In one of the earliest examples of a Looney Tunes character walking on air before plummeting to their doom, Flookey accidentally falls into giant vat of water, marked by the crude yet ferocious splash of liquid covering the entire screen.

Deliberately, Clampett hides the contents of the vat for a few seconds, only revealing it to be a barrel of rubberizing solution upon the arrival of the next scene. It builds a stronger comedic payoff, and a payoff that is especially strong when met with the animation of Flookey struggling to gulp a mouthful down.

Carl Stalling’s muted, sardonic score of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” is perfect accompaniment for Flookey’s antics. It’s a sarcastic antithesis to the saccharine antics of Pluto that theatergoers were so accustomed to. The juxtaposition grows as Flookey uses his tongue to wring out the excess moisture in his head, which sprays the entire screen. Crucial to much of the cartoon’s success, the scenario is whimsical and unrealistic, but grounded in tactile, kinetic movement. That very disconnect is a big part of the cartoon’s humor.

Shoe hands, as it turns out, can make for some rather clunky accessibility. As he struggles to free himself from the barrel, he ends up tipping the entire vat over, spilling rubberizing solution all over the floor.

Tactility and elastic motion is huge in this cartoon, and thankfully behaves as it should. Bob Clampett had lamented about how his unit was seen as one of the lesser units, the “A” unit animators over in Chuck Jones’ or Tex Avery’s units. Clampett’s animators, Norm McCabe and John Carey especially, are certainly talented, but it is a very good thing he was able to pull the short off as he did.

Had the cartoon suffered from poor key animation work, poor assistant work or poor inking, muddying up the kinetics of the motion, this short could be a recipe for disaster. Thankfully, that is not the case, as we see with Flookey struggling to unstick his chin from the solution. Treg Brown’s velcro and electric guitar twang sound effects paired with the stagger of the animation make for a convincing effect that is still whimsical and energetic in its execution.

When Flookey does manage to unearth himself from his position, that’s where the real fun comes in. Having ingested the rubberizing solution, Flookey is turned into a literal rubber hose character, his limbs turned to unstable rubber noodles as he struggles to walk.

A blank stare at the camera for good measure. Much of the pacing in this short borrows from the philosophy of Porky’s Naughty Nephew (or even The Daffy Doc, whose own scene in question is an extension of Nephew): a character pauses after having some part of his body go out of control, stares at the camera in a moment of calm, and the next slightest action causes something to fly off the wall.

Porky couldn’t get his head to stop ringing in Nephew, and then his snout. Daffy couldn’t get his body to stop inflating in Doc, and everything went to pieces after a brief moment of calm. Here, when Flookey does finally get a hold on his rubbery limbs, a hiccup sends him catapulting into the air and bouncing on the ground, slamming up and down like a basketball—with hollow, echoey rubber ball sound effects to prove it.

To stress on the aforementioned parallels, Flookey’s cautious resuming of his normal walk interrupted by another spastic bout of jelly legs, hiccups, and uncontrollably body slamming directly mirrors Daffy’s troubles in The Daffy Doc. Clampett’s comedic sensibilities continue to grow more apparent—this scene with Flookey certainly aligns with his philosophy that hyper antics are at their greatest when there’s a build up and a breakout. Flookey trying to walk is the build up, the side effects of the rubberizing solution are the breakout.

While the next sequence is dated by today’s standards thanks to the ever evolving nature of pop culture, it still remains enjoyable regardless of audience background because of how amusing the drawings are. After realizing his face is as malleable as actual rubber (thanks to a ferocious, elastic slap in the face wonderfully elevated by Treg Brown’s “PWOOOING!” sound effects), Flookey decides to have some fun.

Cue a barrage of celebrity caricatures, all reused from 1936’s The CooCoo Nut Grove thanks to the brilliant mind of caricature artist T. Hee. Celebrities spotlighted here include Edward G. Robinson, Edna Mae Oliver (for whom, amusingly, the camera pans out for to account for the length of her face), Clark Gable—likely one of the most reused of the Grove caricatures—and Hugh Hubert, accompanied by a fitting “laughing” score from Carl Stalling. After all, it was Hubert’s laugh that Daffy appropriated for his own iconic shrieks.

The transition between each celebrity is smooth, elastic, and swift. Flookey’s face has solidity and form to it, a nice foundation of construction, which is crucial in a cartoon that places so much value on the manipulation of his body.

Flookey conveys what little thoughts he has as best as he knows how.

Cautious walking resumes, as do rubber hose antics. Once again not paying attention to his trajectory, Flookey ends up walking along an incline, with one side of his legs short, the other long. Note the “NOTICE — NO DOGS ALLOWED” on the cork board in the background.

While it may seem easy to dismiss much of the cartoon’s antics as being old fashioned and “that’s just how the ‘30s were”, that’s not the case. By 1939, rubber hose was out of fashion, slowly being replaced by the pear and sphere construction of characters in the coming years. Characters didn’t take off their ears and tip them like a hat as Felix the Cat once did—that was seen as trite and archaic by this point. Impossible antics and body morphing so prevalent in the earliest Bosko cartoons have been replaced by an attempt to mimic the Disney philosophy of the illusion of life.

Porky’s Tire Trouble embraces the best of both worlds. It embraces the spirited, free for all nature of the rubber hose era and the base of its ideas, all while wrapped in the more solid, believable construction, acting, mechanics, and execution of late ‘30s cartoons. Rubber hose animation with actual elastic, kinetic properties, a luxury the hands behind the actual era seldom had since animation was so—and still is by this point—new.

In any case, a tumble sends Flookey into another spastic bouncing fit. He’s sent flopping over to a funnel placed in a jar (and a closer look at the background reveals a barrel with a spigot marked with the telltale XXX of alcohol—is Porky involved in some sort of illegal moonshine distillery operation?)

Flookey’s faces from the depths of the jug when he gets trapped are almost funnier when he’s upside down than when he’s right side up, where the focus is on his face—the vacant, constant morphing of his eyes is hilarious, especially compared with his spastic body movements. Keeping the funnel on is a nice touch, as it looks like a collar when upside down, adding a lot more than just a jug.

Compare this scene to Flookey freeing himself from the jug than a scene from a Chuck Jones cartoon (such as The Night Watchman) where Tommy Cat gets his foot stuck in a jar. Clampett’s movement is much more erratic, frenzied, and more attention is diverted to the frantic reaction of the character, whereas Jones prioritizes a character’s calculation of the event and the believable, cute antics therein. As is a prevailing theme throughout this entire venture, comparing how one director approaches the same subject differently than another continues to be fascinating.

Luckily, Flookey does manage to squeeze himself free from the vice, but is quick to stumble into another problem: a set of stairs. Again, Clampett doesn’t beat around the bush—the action happens fast, the impact is fast, and the resolution is fast to prevent monotony and maintain spontaneity.

When he first collides with the stairs, Flookey is flat as a pancake before popping into a solid form—yet another indication of just how imperative strong construction is for the sake of these gags. A literal Flat Foot Flookey is funny. A literal Flat Foot Flookey popping into solid form in the same affected shape adds more energy, more pop, more fun.

And fun is indeed rife when Flookey gets up from the stairs, walking along as though nothing had happened, his body now a solid set of stairs. The side shot is the nail in the coffin in making the gag read clearly—the stair shaped body is amusing already, but extra laughs are garnered and payoff is stronger when we see just how snugly his body fits into the negative space of the stairs.

As such, his smug, head waggling strut is the icing on the cake. Especially when the boss lugging a stack of tires approaches, absentmindedly scaling Flookey like a set of stairs. Carl Stalling wonderfully juxtaposes the two personalities through music—the arrangement of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” for Flookey is light, comic, whereas the boss’ is razzing, brash, domineering. Clampett does a fine job of dividing the attention between both characters and their actions equally. One could compare Flookey's smug strut to Daffy's in Baby Bottleneck, who, in that case, happens to idly hum the aforementioned song. The whimsicality of this cartoon's mechanical set-up--particularly the gags involving the machinery--could be seen as a forbearer to the playfulness of Bottleneck's own factory atmosphere.

Eventually, the boss does grow wise, as it takes a spill onto the floor for him to notice. As he writhes on the floor, the tires he was carrying all fall around him and lock him in a bind.

“A DOG!” It sounds as though his voice switches from Bletcher to Blanc with the boss’ next outburst of “I HATE DOGS!”, which wasn’t unheard of.

While the close-up on the boss suffers from a little too MUCH freneticism and constant movement (very few poses are held, and the actions grow difficult to keep track of, as well as an abrupt jump cut to account for more composition space), it certainly fits the spirit of the cartoon, and is plain fun to look at.

Interestingly, Clampett (or Warren Foster) slips in a cut-away joke, which wasn’t incredibly common in these cartoons—at least, absolutely unrelated cutaways. Upon the boss’ proclamation of his hatred for dogs, the hotdog from Porky’s lunch (debates on the implications of Porky’s cannibalism irrelevant) turns into an anthropomorphic dog. It's very quick to slither behind Porky’s lunchbox for cover.

While the gag nowadays isn’t very funny, the pure novelty of an unrelated cutaway gag in a Looney Tunes cartoon is worth noting. I can’t remember any other cut-away gags off the top of my head that are as unrelated to anything else at play, but I’m sure they exist, especially cartoons thick with celebrity caricatures. Either way, it’s certainly rare enough to warrant attention.

The boss hiking up his chest has a nice weight to it, but could benefit from the aid of Treg Brown’s sound effects to really accentuate his gumption. In any case, sound effect priority is placed on his heavy footsteps as he marched towards Flookey.

Now is the time for urgency as Flookey folds into himself. Though it’s difficult to discern due to the momentum of the fast pan, the background has a lot of amusing details in it, such as the back door being completely broken off of its hinges.

Carl Stalling’s music score is infectious throughout the entirety of the cartoon, but it grows particularly energetic in the midst of a chase. Evolving from a hurried minor key to a chipper, brassy, frenzied but mischievous major key clues the audience that the chase is to be enjoyed and the stakes aren’t all that high—this is a cartoon about a dog that swallowed rubberizing solution, not a melodrama.

“NOW I GOTCHA!” The boss manages to grab ahold of Flookey’s tail. Thankfully, the side effects of ingesting rubberizing solution come in handy—Flookey is able to contort himself through one door and out the other, approaching the manager from behind and biting him on the ass. Major kudos to clear actions, experimenting with perspective, and simple yet dynamic composition. The diagonal angle of the wall both makes the staging feel more natural, as well as give it an added boost of energy, seeing as diagonal angles convey energy.

“YOWWWWW!” Flookey’s animation of him knocking into the boss after biting him is a little lost in translation; he loses his footing, causing himself to rocket into the boss and send them whirling in a tailspin, but everything happens so quickly that it instead reads as though Flookey knocked into him on purpose.

Enter more John Carey animation as Porky slides into the scene. As is the case with many of Clampett’s Porky cartoons, it’s clear his heart is invested in Flookey’s antics, not Porky’s; Blanc's delivery of “Hey, eh-dee-deh-don’t hurt that eh-deh-dee-duh-dog!” is directed very flatly and sounds as though Porky is mildly inconvenienced, bored at best rather than trying to save his beloved pet from any potential abuse.

The boxes labeled “HANDLE WITH CARE” in the background serve as a snide commentary to the boss’ action, who slings the poor pooch out the door as hard as he can.

But, of course, literal rubber physics prevail, and Flat Foot Flookey rebounds off of the tree he hits with ease, mowing the boss over right before he can begin to lecture Porky.

Stalling reverts back to a happy motif of “Mutiny in the Nursery” to signify that its all in good fun and that Flookey is back on top, literally. The camera pans to reveal Flookey perched on the boss’ behind, hat on his head as he barks and poses like a seal—a not so subtle dig at the boss’ animalistic origins. Both silhouettes of the characters are strong and clearly form the illusion of a deal perched on a rock begging for treats—strong curvatures and clear negative space help to make the illusion flow more clearly and behave naturally.

With that, more wrestling ensues as Porky frantically dances from afar, his power (or lack thereof) very clearly establishes on the hierarchy between walrus, dog, and pig.

Such is furthered when the boss literally shoves him out of the way. There will be no heartfelt moment of pleading for mercy or talking about how much Flookey means to Porky—the boss is quick to sling the dog out the door yet again, with Porky powerless.

SLAP! Physics prevail yet again. When Flookey hits the floor after colliding with the boss, there’s no antic or follow through—he just stays in that one position. Here, it works to the betterment of the comedy, the abruptness providing the right sort of energy and bluntness demanded by the scene.

Just as the boss is about to throttle and sling the pooch some more, he suddenly has a change of heart. Stalling’s music score melts from triumphant and playful to suspenseful and careful, mimicking the movements of the boss as he prepares to lay Flookey down as gently as possible outside.

Even then, he still ends up throwing the dog out, with Flookey mechanically gliding off-screen. At any rate, the overall message of the gag is clearly conveyed.

The care and caution the boss exercises when placing Flookey down is immediately refuted by the loud slam of the door and automatic bolting of the lock. Delighted with his handiwork, the boss listens to hear if the sound of rubber bouncing is still reverberating through the door.

Indeed it is.

Atonement for the boss’ crimes is granted in the form of one giant waffle maker turned tire compress. The boss flails around silently—was it a budget issue and intended to keep costs low by not recording a scream? Was a scream too uncomfortable? Both seem plausible.

In any case, it’s not the volume of the boss’ protests that matter, but the payoff. We iris out on the newest member of the Snappy Tires Company name, Carl Stalling’s trumpet score a victory cry fading into the darkness.

Many of Clampett’s cartoons seem to succeed more in the finer details rather than compared to the big picture, which could be said about Porky’s Tire Trouble. Tire Trouble is one of the last Clampett Porky cartoons of its kind—Clampett has a few Porky cartoons that are still plenty fun (Wise Quacks, Porky’s Last Stand, and Prehistoric Porky are some that come to mind), but not nearly as many are as inspired as this one, nor as enthusiastic. Some of Flookey’s antics could be seen as a little too repetitive (particularly during the climax), there are some awkward moments due to awkward cutting, unfocused animation, or unclear staging, and the short seems to come to an abrupt end--a common fate for many of these upcoming cartoons, regardless of director.

In any case, the parts outweigh the whole. Tire Trouble has some of the most elastic, energetic, and playful animation we’ve had the honor of witnessing thus far.

Imagining the same cartoon made even 5 years prior wields incredibly depressing results—this premise could be incredibly trite if it didn’t have the benefits of the animation refinements present in 1939 (which was still a ways from true refinement for these shorts, reached probably around 1943 or so) or the enthusiasm of Bob Clampett. This is a cartoon that demands a LOT of energy, and thankfully that quota is met—Tex Avery may have been the only of the current directors who could have met the same energy demand, and even then, he was past his demand for screwball characters.

Fun is a very vague descriptor, but a very appropriate one. This cartoon is, in one word, fun. The premise is fun. The animation is fun. Carl Stalling’s music is fun. Flat Foot Flookey’s design is fun. The backgrounds are fun. Even if certain things aren’t exactly thrilling or exciting—especially today, when it’s so easy to allow hindsight bias to skew one’s perception of these earlier cartoons—they’re still very fun, and that’s as honorable of an objective as any.

With that, Porky’s Tire Trouble is certainly worth a watch. Bob Clampett purposefully establishes the cartoon to read as an imitation of Disney, only to make it twice as hyper, insane, and twice as funny, all while still very much appreciating the material that he’s twisting. It holds up incredibly well even for today, and one can only imagine how much of an impact it made in 1939. The elastic, frenzied animation here is a fitting precursor to what would soon blossom and be a domineering aspect of Clampett’s best cartoons.

Enjoy! The cartoon is also available on HBO Max.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment