Disclaimer: This review contains racist stereotypes, content, and imagery. Presented purely for educational and historical context, I wholeheartedly condemn said depictions, but encourage you to speak up if I accidentally say something that is harmful or insensitive. It is never my intent to do so and would like to take accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: March 11th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Ernest Gee

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Interrogator, Police Radio), Billy Bletcher (The Phantom), Danny Webb (Police Chief, Hugh Hubert)

Bob Clampett’s adoration of pop culture has been noticeable from the start, but it’s integration has become increasingly more obvious. Whereas The Lone Stranger and Porky burlesqued the wildly popular Lone Ranger franchise at the time, Porky’s Movie Mystery serves as another burlesque—this time of the Peter Lorre Mr. Moto films. Cashing in on the Charlie Chan craze of the late ‘30s, John P. Marquand’s novels received the film treatment, with Hungarian actor Lorre starring in 8 Moto films in the span of 2 years.

Here, Clampett cashes in on the craze by modeling Porky after Lorre’s Moto. Right away, the opening “Starring PORKY PIG” sequence succinctly sums up the atmosphere of the cartoon, the music score melting from a triumphant fanfare of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” to “The Japanese Sandman”.

Indeed, Mel Blanc sounds exactly how one would picture the above screenshots sounding: like Porky Pig putting on a terrible Japanese accent with a stutter. For better or worse, Clampett’s growing disinterest with Porky comes in handy this time around—it takes him 3 and a half minutes to first appear in his own cartoon, and lines of dialogue are thankfully relatively sparse, though not nearly sparse enough.

In any case, Porky, playing the role of Japanese spy Mr. “Motto”, is tasked with tracking down a mysterious phantom terrorizing the Warner Bros movie lot.

The fictitious disclaimer claiming “Any resemblance this picture has to the original story from which it was stolen is purely accidental” may very well be one of the funniest parts of the cartoon. Some of the disclaimers can get a little too corny, but this is easily one of the better ones for its conspicuousness.

Walter Winchell marks the first celebrity appearance in the cartoon, his off-screen, rapid fire narration dubbing himself as Walter Windshield. We never see him, just the still shot of a radio broadcasting his report. Clampett continues to lean on the economic side, masked under the guise of creativity—which, to be fair, does work in this instance, a lone shot of the radio seemingly more mysterious than showing the Winchell caricature on-screen.

“Flash! For weeks, a mysterious phantom has been haunting the studios in Hollywood, panicking the actors, ruining pictures, and creating havoc of the film capitol.” Winchell’s narration belies the moody pan of the Hollywood night scape, spotlights contrasting nicely with the surrounding dark palm trees and mountains.

Upon the declaration that the phantom is now lurking on the Warner Bros lot, the camera immediately trucks into said lot, cast in a dark, eerie gloom. A piercing scream from off-screen compliments the melodrama, as does the animation of the phantom’s silhouette lurking in the shadows.

With Clampett’s innumerable pop culture burlesques, it cannot be said that he wasn’t passionate about them—while the opening has been conservative in its animation, it’s elsewhere thriving in atmosphere, with camera movements possessing a life and energy of their own.

Our phantom is the ultimate caricature of a cloaked villain—he IS a cloak. Whereas Tex Avery caricatures conniving, cloak hugging villains in cartoons such as Milk and Money and The Blow Out, Clampett takes the caricature to the next level by having the villain be purely cloak and nothing more.

To cast any villain of this caliber as someone other than Billy Bletcher in the year of 1939 would be a sin. Even all these years later, his signature evil cackle is welcomed with open arms. Here, our villain bellows said signature cackle before dipping into the shadows.

On the topic of The Blow Out, the animation of the police chief operating a switchboard from the aforementioned cartoon is repurposed yet again here, his silhouette double exposed atop police cars racing in the streets, uttering the same monotone “Calling all cars” heard in most cartoons of this genre. Indeed, the police cars exiting the station are also reused from The Blow Out.

No police chase montage is complete without a newspaper headline flashing in the screen.

Afterwards, we cut to more reused animation, this time cribbed from Cinderella Meets Fella of a police van whirling down the streets. Reusing animation was a common and economical practice during the Depression era—theater audiences who saw these shorts one time and quite possibly never again certainly weren’t going to notice what was reused and what wasn’t. Even then, Bob Clampett was notorious for refusing animation, a trend that he never seemed to outgrow.

While it can be a detriment depending on how well the reused animation gels with the current style of the short, it’s, in my eyes, more fascinating than anything. Much like trying to track which animator worked on what part of the cartoon, scanning for animation reuse feels largely like a scavenger hunt. It’s difficult to use as a point of criticism, at least for a cartoon such as this one where it generally blends together well.

Another newspaper headline serves as a segue to the next sequence of a cop “quizzing” potential subjects—notorious movie villains.

And who’s better suited for the role of a movie villain than Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein(‘s monster)? In another attempt to be cinematic, the officer interrogating a terrified Frankenstein is depicted only through silhouette, grilling the monster via shadow. The framing is particularly nice, both of the domineering presence of the officer and the light hanging over the monster’s head. It makes him appear trapped, cornered in multiple angles, his sitting posture conveying his inferiority.

Blanc’s line deliveries are pretty standard, but, when speaking of Mel Blanc, that’s code word for “very good”. Certain lines of “Stop beatin’ around the mulberry bush!” and “You blankety blank monster!” are flat out dumb, but seem to embrace said dumbness and transform it into playfulness. The same could be said with the animation of the monster anxiously gnawing on his nails like a typewriter, typewriter clicks and clangs thoroughly completing the transformation.

With that, the reveal of the copper is standard Clampett humor, who seemed to enjoy his size disparities. Casting the shadow on the wall via double exposure causes the picture to blur quite a bit, but the overall message of the gag is very clear and doesn’t need to rely on the little details to get through.

Transitions between newspaper headlines have been slowly growing in their creativity. The first newspaper was displayed with just a cross dissolve, the second seen sliding into frame. Here, the classic zoom-into-view tops off the interrogator’s cries of “Are you the phantom!?”, the headline indicating that the phantom is still at large.

Cut to one at large phantom, with Billy Bletcher bellows abound as he creeps along the studio.

The phantom twirling his cape around his torso is pure showboating, as it soon trails behind him when ascending a spiral staircase.

Cue a long pan of the phantom ascending the stairs, Carl Stalling’s accompanying piano flourish practically a gag in itself as it continues to rise in scales.

Same applies for when the phantom exceeds the staircase, continuing his ascension on air as Stalling’s accompaniment grows higher and shriller. Sometimes “Mickey Mousing” the music score can become routine, unimaginative, but here it works to the gag’s favor—without the literal accompaniment, the gag may be politely amusing at best.

A payoff is granted in the form of a ceiling beam, the phantom hitting his head on the wood. Rather than plummeting to the ground, he does a quick take, quick to cling to the metal pole supporting the stairs as he slides down like a pole. Once again, Stalling’s music score dutifully follows suit.

Continuing his trek through the studio, the phantom creeps along the decrepit room, cobwebs and cracks in the wall showing its age, as well as a faded movie poster for Birth of a Nation, a movie that is very, very much outdated in its philosophy.

After a few more furtive head shakes to ensue he’s not being followed, the phantom zips into a room and shuts the door.

Cue identity reveal: the phantom is The Invisible Man, a nod to the 1933 Universal Pictures film of the same name.

If the dressing room door wasn’t enough of an indication, the phantom’s undressing and Bletcher’s declaration of “Yeah, I’m the Invisible Man! A phantom to those guys,” certainly cements any suspicions.

Carl Stalling’s music score is retrograde in numerous ways: one, it’s a J.S. Zamecnik score, tapping into both Stalling’s musical roots as a silent movie accompanist as well as the phantom’s outdated existence, and two, was used in quite a few of Norman Spencer’s Looney Tunes scores during the mid ‘30s, such as Jack King’s Shanghaied Shipmates.

Invisible gags ensue, particularly with the phantom eating an apple. The audience is granted with the visual pleasure of observing the phantom’s digestive process, bits of apple magically rebuilding into a whole as it lands in his stomach. The apple remains for the remainder of the phantom’s spiel.

As it turns out, the phantom’s heckling is a symptom of rebellion against the movie studio. “They star me in one picture, then DROP me!” That his monologue is “I’ll crack every camera, I’ll break every reel, smash every set, scare every STAR outta Hollywood!” and not “I’ll crack every camera, I’ll break every reel, smash every set, scare every HEEL!” is criminal, but his motives being established is much more important than satisfying rhymes.

Clampett eats up the headline shots, an easy way to save money and save time.

With that said, the employment of stock live action footage to display the unrest of the citizens is so whimsical and hilariously—and purposefully—antithetical to the cartoon that it gets a pass. Live action stock footage can often be used to make what would be a regular, ordinary bit of action much more playful, purposefully jarring, and funny, as is the case here. Warner Bros would continuously dabble in the stock footage department, though relatively sparingly, which allows it to maintain its punch when it is used.

Another newspaper headline answers the qualms of the angry citizens: their beloved Mr. Motto is on vacation. Note the weather and date on the newspaper: a fair and balmy forecast for Friday the 13th. Clampett’s Porky’s Last Stand also casts the cartoon’s date as the 13th, revealed by a small calendar in one of the backgrounds. Immediately synonymous with hard luck, the date also provides an extra layer of playful mischief to the cartoon(s).

“I don’t care if he IS on a vacation!” Animated by John Carey, Danny Webb voices the chief of police, demanding one Mr. Motto.

Carey’s elastic, fluid animation is brilliantly displayed when the chief slams his fist down on the desk, prompting all of the objects on top to fly into the air. The miscellaneous objects maintain their construction and solidity, whereas the desk turns elastic to bend to the whims of the motion while preserving its own firmness. Such solidity was a strong point of Carey’s animation, as was his perspective animation, evident in the head tilts on the chief.

More potentially mundane action is disguised in a playful finish that also happens to save money; rather than displaying a montage of switchboard operators, Clampett instead cuts to an aerial shot of the globe, Sara Berner’s “Calling Mr. Motto!”s overlapping as the connection lines snake all through the globe. The comets and planets in the background are simplified to a degree of caricature, gelling well with the overall mischievous execution of the scene. An intricate painting of the solar system would certainly be pretty, but too serious and pompous for a scene centered on trying to get someone to end his vacation early.

As such, we then segue to the deplorable portion of the cartoon: Porky as Mr. Motto.

To be fair, Porky’s idea of a vacation consisting of him sitting on a deserted island reading a book is pretty amusing. It’s the stereotypes that ruin it, and the cemented reliance on said stereotypes to give Porky more personality. Very clearly, Porky was cast as Motto not only as a vehicle to further Clampett’s love of burlesque, but as a way to make him seem more “interesting”. Clampett would cast Porky in a number of these dress-up cartoons almost exclusively for the next few years, and the ones that didn’t rely solely on racial stereotypes do make for a fun outing.

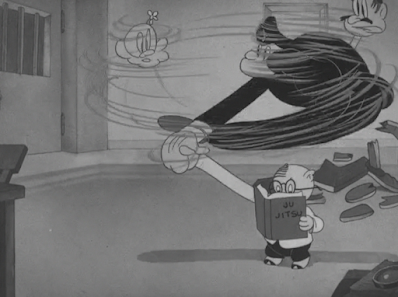

As mentioned previously, Porky’s dialogue throughout the cartoon is exactly how one would envision Porky putting on a racist accent, so transcriptions of his dialogue shall be spared. Here, he mutters aloud as he reads his book on jiu-jitsu, a take on Peter Lorre’s Moto being well versed in judo, something that was only hinted at in the Moto novels.

Animated by Bobe Cannon, Clampett continues to embrace the “Clampett Porky double take” as he spares a quick glance at the coconut next to him, ringing like a telephone. Though a shame to be wasted on this cartoon in particular, Porky cracking the coconut open and answering it like a telephone, with one half as the receiver and the other the mouth piece, is so stupidly playful that it works.

Clampett’s straight laced execution of Porky talking into the coconut as though it were a real phone, with no hesitation or pauses to call attention to said coconut phone, allows a potentially corny gag to be embraced and welcomed.

After learning about the phantom, Porky assures that he’ll be there right away. A close-up of his departure is animated by John Carey; with a tug of a string, the convenient outboard motor attached to the island whirrs to life.

Much like the coconut phone, that such amusing transformations of these physical objects has to be wasted on this cartoon in particular is a shame, because they are genuinely amusing. The speed in which the island takes off like a boat, complete with an engine whirring and a jaunty score of “California, Here I Come”, all while Porky pays no attention and continues to engross himself in his book is wonderfully executed. Though the action is as playful as it can be, following the Tex Avery approach of playing it smooth and calling little attention to the abnormality makes the gags all the easier to bear.

And playing it cool, Porky does. So much so that he doesn’t bother detaching himself from his book once the island-turned-boat smashes to pieces into a nearby dock, sending him somersaulting into the air and landing conveniently into a docked plane.

No excessive scene of Porky trying to get the plane to start either. Echoing memories of Porky in Wackyland, the plane takes off as soon as he makes contact with it, soaring through the sky in a perspective shot. The entire time, Porky doesn’t dare to look up from his book. A string of events tied together that could come off as corny and monotonous had it not been executed with the same nonchalance and confidence.

It also doubles as a commentary on the Moto films as a whole and its priority on action scenes (not given the same highlight in the books), most explicit when Porky’s crashes through the ceiling of the police department and comes out totally unscathed, book still in hand.

“Mr. Motto!” Chiefy is pleased, reciting the wisdom of Bert Gordon’s The Mad Russian, whom Clampett would later dedicate an entire cartoon to with Hare Ribbin’: “How do you dooo?”

Porky shakes the chief’s hand, more parody of Lorre’s action packed Moto as the hulking officer is sent whirling around in the air. Signature Clampett ball-o-violence multiples ensue, freeze frames revealing multiple heads popping out of the smear. All things considered, the size disparity between tiny, pudgy Porky swinging this giant barrel chested cop like it’s nothing—with one hand, reading a book in the other—does make for a natural comedic setup.

Any positive reputation that the previous gag did maintain is squandered by more racial stereotypes; it seems as though there was a rule instated that any golden age cartoon with racist Asian stereotypes must have the obligatory “so sorry” line.

In fact, one of the most amusing parts of Porky’s performance stems from his stuttery “Ee-eh-ee-eh-ee-eh-ehh-shhhhhhh!”, which succeeds because it seems to be one of the only gags that doesn’t place such any emphasis on racial humor—just Porky humor.

Nevertheless, Porky cautiously searching for clues with a magnifying glass at least poses some significance. The fake magnifying glass gag had been used time and time again prior to this cartoon, but would be salvaged here in Clampett’s much more palatable The Great Piggy Bank Robbery. While it’s almost certain he wasn’t thinking back to this cartoon when slipping the gag in that short, the consistency is interesting to note regardless.

Curiously, it seems as though a splice was made in the cartoon. Porky approaches a director, his authority established immediately by his garish clothing and beret o’ pompousness. Just as it seems that the director and Porky are about to have any sort of confrontation, the camera cuts to the villain, emerging from the foreground and laughing nefariously. A jump in the music also informs the change. Though using the Porky Pig 101 DVD print for this particular review, it seems that the splice is present in unrestored and colorized versions as well.

Regardless, the phantom continues to creep along before noticing Porky’s presence. Rather than allowing his hat to float in midair, seeing as his invisibility has been established to the audience, Clampett instead gives the villain a black, opaque face instead, furthering the physical reliance on the phantom’s cape. The “exposed” hands and fingers are a particularly fun detail as well, as though to stress the villain’s vulnerable status.

A return is made to the villain’s invisible stature, particularly when he needs an excuse to hide from Porky. His cloak is disposed of in a nearby trashcan; the cloak briefly obscuring the foreground and the phantom’s “body” adds an extra layer of playfulness, rather than showing him undressing himself fully exposed. An air of mystery is still maintained, as well as sardonicism at the reliance of such a tried and true villain trope.

Movie sets mean movie posters, and the phantom is quick to use his settings as an opportunity to blend in. As such, he masks himself on a poster for “Great Guns” starring one Lotta Dimples. Ironically, there was a film by the name of Great Guns, but not until 1941 for 20th Century Fox, starring none other than Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.

Rather than fleeing when the coast is clear from the impending pork, still trekking by with his magnifying glass, Clampett’s typical bite is exuded in the form of a swift kick in the ass. It comes as a bigger insult when in conjunction with Carl Stalling’s music score, purposefully dainty and lighthearted to reflect Porky’s innocence rather than a nefarious reflection of the phantom’s impulses.

Cue the tried and true fight scene. Which, despite everything, is yet another higher part of the cartoon. With an axe conveniently placed in the foreground, the phantom swings at a dazed Porky, who narrowly avoids the blade by literally jumping out of his pants—animation upcycled from Clampett’s Inj*n Trouble. The addition of the glasses at least call more attention to Porky’s outfit and how it’s physics can be manipulated, but there does seem to be a particularly heavy reliance on recycled animation in this cartoon more than other ones.

Porky’s attempts to dodge the blade are also snappy, which fares much better than a drawn out, dramatic chase. The melodrama in this cartoon is as much of a parody as everything else in this cartoon, which, again, works to its favor.

On the topic of parody, Lorre’s Moto and his affinity for judo is once again tapped into a cornered Porky as he desperately consults his book on jiu-jitsu. All things considered, the dot eyes as he frantically reads through is a fascinating detail—there are quite a handful of distance shots where Porky has said dot eyes, but never in a close-up such as this one. The glasses add that extra stylized, graphic leeway, though it does work best for that very fleeting second.

Cue the comeuppance, which is one of the most amusing parts of the short: rather than Porky struggling to grab the axe back in his clutches, he’s able to pause in mid-air and snatch it without any sort of antic or follow through on the animation. The abruptness is both a reflection and caricature of his strength, which is conveyed to new extremes in another certified Clampett ball-o’-violence.

Treg Brown’s frantic woop-woop-woop sound effects, along with the stars and balloony multiples on the characters, serve as the perfect absurd accompaniment to the gag of Porky gingerly stepping out of the fight to place the axe down, out of harm’s way, and zip back into the ring.

Though Clampett would reprise the gag in Porky’s Picnic, a hungry lion all too happy to pause as Porky recovers a spectating Petunia from fainting, the gag here, in spite of Porky’s egregious role as a whole, works better with the fight still erupting in the background as though nothing had happened. Once more, it’s that Averyesque philosophy of playing any absurdities as nonchalantly as possible that get the most points.

With the power of jiu-jitsu at hand, Porky has little difficulty disposing of the villain, punching him in the gut and throttling him around in the air for good measure. Again, despite the circumstances, to see Porky as the brave hero gut-punching villains with this level of immunity, is an admittedly fascinating sight to see—he’s punched many a villain time and time again, but never with the explicit invincibility and confidence as he does here. It is a rather fascinating anomaly.

With the fight coming to a close, the Walter Winchell caricature narrates overtop the action. The delivery of “Flash! This is Walter Windshield again!” is undoubtedly Blanc’s voice before switching to the “real” Winchell, who is not Blanc.

John Carey’s animation in this particular scene possesses earmarks that would continue to grow for the next few years—before, his animation was typically characterized by long, pill shaped pupils and a long snout on Porky particularly, but here, the dimensional head tilts, wide snout, and gorgeous elasticity as Porky bounces on the invisible man’s gut all foreshadow Carey’s coming earmarks as an animator.

Likewise, Norm McCabe’s animation of Porky unearthing a convenient anti-invisible juice gun is just as easy to identify, with the pronounced double eyebrows, big cranium, pronounced lower lip, and overall more streamlined, flat, even comic strip-esque appearance of Porky, particularly in the eyes and the way they converge. Here, the Winchell narrator dutifully follows Porky’s actions: “Mr. Motto is ready to shoot the anti-invisible juice! He raises the gun!”

Back to Carey’s animation of Porky spraying the gun. “Ladies and gentlemen, the invisible phantom is…”

The payoff in 1939 was likely much, much, much funnier and more satisfying than it is today: T. Hee's caricature of actor Hugh Hubert from The CooCoo Nut Grove performs his signature woo-woo giggle as we iris out.

Porky’s Movie Mystery is a very mixed bag. Some of the more salvageable details are worth noting—the live action stock footage is funny, Bletcher’s performance is fantastic as always, gags not hindering on racism such as the island turned motor boat or removing the axe from the fight scene are brilliant, and there are spots where there does seem to be brief flickers of energy. The camera work is fast, the narration energetic.

As a whole, however, Movie Mystery is a very weak cartoon whose reliance on multiple crutches digs the hole that it’s gotten itself into. The most obvious being, of course, Porky as Mr. Motto.

Even without the wildly racist get-up and dialect, Porky here is incredibly weak and one-dimensional. The humor solely relies on the stereotypes—as mentioned before, it seems quite obvious that Clampett cast Porky as Motto just as a way to “freshen him up” and make him seem funny, not because he thought he was a character suited to play the role. As such, any and all humor from Porky is solely dependent on racist stereotypes. So, when the stereotypes are unfunny, and one relies on unfunny stereotypes to be funny, everything falls apart at once. Porky stuttering as he shushes the police chief is funny only because it's a piece of business unique to Porky and Porky alone, not something relying on racist caricatures.

Even if Porky were just his regular self or another, more moral depiction of a spy, the cartoon would still maintain the holes it has. A lot of padding is granted through still shots and pans—long pauses on newspaper headlines, long pans, still shots, a disclaimer, as well as the constant animation reuse.

Again, this is something that’s easier to critique in 2022 than 1939; the black and white cartoons were cheaper than the color Merrie Melodies, and the effects of the Depression were still being felt. The type of availability we have now, where we can pour back to old cartoons for reference and freeze frame minuscule details, wasn’t present back then and these cartoons weren’t made for that sort of availability in mind. So, really, someone heading out to the movie theater on a Saturday and watching a Looney Tunes cartoon before the main feature isn’t going to notice the long pauses or reused animation or abrupt cuts like we do now.

Still, there are other cartoons from the same time that don’t rely on that reuse and don’t rely on those static shots, either. Both from Clampett himself and his colleagues. Overall, even in spite of the most egregious and obvious of flaws, Movie Mystery is a side effect of Clampett phoning it in and isn’t a cartoon excessively worth one’s time.

But, as always, I’ll provide a link regardless—view with discretion.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment