Release Date: April 1st, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Rooster, Worm, Duck), Danny Webb (Fox), Dorothy Lloyd (Chicken, Whistling)

The title card serving as the most interesting part of the cartoon is never a reassuring sign, but it is at least a sign. Chicken Jitters is an excellent example of Bob Clampett at his worst—which, all things considered, isn’t terrible. Perhaps that’s the problem; the cartoon isn’t terrible by any means. In fact, it isn’t anything by any means.

A very strong example of Clampett’s Porky burnout, Chicken Jitters entails a variety of chicken gags on Porky’s farm, as well as a stand-off between a hungry fox and a baby duckling.

As many Clampett cartoons do, Jitters opens to an establishing pan, a still centered on a sign gag: PORKY PIG’S POULTRY FARM — EGGS FOR SALE, 40¢ PER DOZ. WITH SHELLS ON — 10¢ EXTRA

The “farmer Porky” genre was something Clampett would tap into from time and time again, as would most of the directors; seeing as Porky is so decidedly humanlike, wearing snazzy clothes, owning a house, owning pets, running a variety of odd jobs, casting him as a farmer was the closest way to tap into his animalistic roots.

A slow pan across the farm is met with a deliberately slow truck-in to save time and money.

Dissolve to a bleary eyed rooster waking up for the morning, scouting for the sun with the aid of binoculars. John Carey's animation is noticeable in the drawn out blinks and general solidity of the drawings. The intricately painted background, particularly the leaves on the trees, frame the scene nicely, arcing around the general vicinity of where the sun is expected to rise, serving as a directory for the audience’s eye.

BWWOOOING! Treg Brown’s electric slide guitar sound effects are always welcome accompaniment, working well with the elasticity of the sun springing in the air. While the sky itself hardly changes in lighting (perhaps not enough time or money to paint a dark dawn sky?), Carl Stalling’s demure, floaty music score of “Monday Morning” provides a warm, cozy dawn atmosphere, serving as an adequate substitute.

Satisfied with the cue, the rooster clears his manly throat, flaps his wings, chest ballooning as he threatens to mark the dawn of a new day.

“WAKE UP, FELLAS!!!”

The pan across the farm is fascinating for a number of reasons. One, there’s a jump between backgrounds that’s hardly noticeable without pausing, but is indeed there. Two, the pan melts into a dissolve to another pan, almost creating a sort of motion blur in the end result, especially with the quick pace of said pan. It works relatively well in movement, the aforementioned splices difficult to notice unless pausing and combing through the frames, but it certainly demands much more intricacy than a regular start-n-stop pan. Perhaps to save the effort of having to illustrate one giant horizontal painting of the farm’s layout.

Nevertheless, said “fellas” are a gang of drowsy chickens emerging from their coops. Each chicken coop is a reference of some kind, whether it be pop culture references such as Blondie and Dagwood and the Hardy Boys, or references to the studio staff.

“The Jones Family” refers not only to the chickens; though Chuck Jones may be the most well known, he had a brother, Dick Jones, who would work in Chuck’s unit. Whereas Fred Jones was unrelated to the family, he too was a branch of the Warner’s staff. “Mother Carey’s Chicks”, on the other hand, is a very clear nod to Clampett unit animator and layout artist John Carey. Each coop has its occupants emerging, dancing and jiving to a swinging ‘30s arrangement of “Old MacDonald” for no apparent reason other than it’s the 1930s and this is modern.

Cue another pan across the farm and into the barn, where we truck-in on the comparatively old fashioned Porky, Stalling’s swing music score turning more domestic and chipper to accompany Porky’s cheerful whistles. Bobe Cannon is once again in charge of animating the pig, noticeable from the tapered mouth shape, buck teeth, and eyelashes as he blinks.

“Eh-guh-gee-geh-ehh-good morning, folks!” Porky pauses his whistling to bid the audience hello, something Clampett seemed slightly fond of, as he did the same in Porky in Wackyland. Allowing the music score to halt for the greeting is a nice immersive touch, bringing more attention to the breach of the audience-screen relationship.

A close-up (including disconcertingly detailed hands, fingernails regrettably present and all) reveals an in-depth look at Porky’s farmer duties: an egg is held up to a camera bellows, a candle on the other end providing light to shine through and see if the egg has a yolk in it or a chick.

Following the rule of threes, the third egg is revealed to have an occupant: a baby chick haughtily sticks its tongue out at Porky, revenge for invading its privacy.

Thank goodness for privacy curtains. Showing the chick’s silhouette behind the curtain allows the gag to linger slightly longer than the alternative, with just an opaque set of blinds obscuring the egg. Frank Tashlin would reuse the setup in a similar but much more whimsical manner in Booby Hatched, baby chicks skiing and ice skating within their eggs to stress how cold they are.

Onto more chicken gags, marked with a transparent iris wipe. A jaunty arrangement of “Chicken Reel” accompanies the aimless waddle of a chicken who struts past a lone ear of corn…

…and the music rises to a rousing crescendo upon the hen’s recognition of the corn. She skids to the goods, pecking at it with her back turned to the audience. Porky’s poultry seem fond of their privacy.

Said privacy is utilized as a means for a gag reveal: a proud hen turns around to reveal her literal corn cob pipe, rocking on her toes pompously. Though the gag is mildly amusing at best, the smoke billowing out of the pipe allows the transformation to read as much more whimsical and playful than any plain transformation between corn and pipe.

As addressed in the past few Clampett analyses, his recycling of animation continues to grow more concentrated and shameless as his filmography stretches on. Here, the animation of a chicken ripping an apple in two to feast on a worm inside and nothing else is reused from the 1937 Tex Avery cartoon Porky’s Garden; the shiver take as the hen struggles to pry the apple open as well as impact lines depicting the fruit’s shininess date the animation, but not enough to be a jarring contrast to 1939 theatrical audiences.

Animation reuse also pertains to future recycling as well. Here, Clampett would reuse the walk cycle of a mama duck and her offspring in his Wise Quacks, another 1939 entry starring Porky. Nutty News would refurbish the cycle, updating the designs to 1942 Clampett standards, but still tracing over the animation here as a reference.

In any case, standard “egg walking with feet sticking out” gag applies, causing trouble when the little runt accidentally gets separated from its family to the pond. Each of the ducks doing the signature Stan Laurel hop not only hints at Clampett’s itch to work with Daffy and the screwball antics therein, but serves as an amusing gag in terms of sound effects as well; each duck hops up with a “put!” sound effect, save for the runt, whose high pitched “poit!” as he turns away differentiates him from the rest. The gag may not be a gut buster, but the sound effects add a lot of playfulness and harmony that would be much too lacking otherwise.

Stalling’s violin score of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” is wonderfully pleasant, cozy and domestic but mischievous as it reflects the egg’s galloping animation, which glides very nicely in conjunction with a rolling horizontal pan.

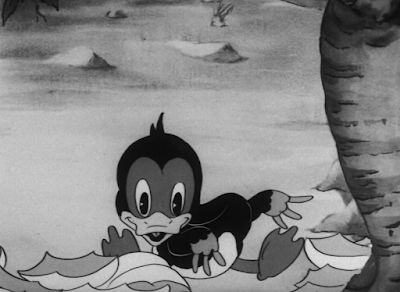

A hearty konk against a nearby tree spawns the gift of life. The animation of the baby duckling hatching from the egg would be reused verbatim in both Clampett’s Wise Quacks and The Henpecked Duck from 1939 and 1941 respectively. In fact, the little duckling here would be a star player in the former cartoon.

Though it would be milked to greater and much funnier lengths in Wise Quacks, Mel Blanc’s cutesy, aimless giggles as the duck are undoubtedly amusing—especially when the camera cautiously pans up to the little fella, prompting him to coo “Hmmm! People!”

Rather than ending the gag right then and there, Clampett stretches it further by allowing the duckling to pull out a portable camera and snap a picture. Even this gag isn’t new, cribbed from The Isle of Pingo Pongo (including a much more crude retracing of the camera in said cartoon), but it’s made much more amusing by the cloyingly cute giggles and vacant stare from the baby duckling.

Recycling continues in one of the most comically bizarre and lazy pieces of reuse; a scene cribbed from Frank Tashlin’s Porky’s Poultry Plant from 1936.

While recycling said scene isn’t exactly the issue, the problem comes in with Porky; rather than modifying the animation to fit the much slimmer, more streamlined, less geometric design of the modern Porky Pig, Clampett slaps the 1939 Porky head on the body of the 1936 Porky, which makes for an incredibly jarring disconnect. Tight budgets, short schedules, and lack of inspiration or not, the decision to update only his head is baffling.

Again, as I’ll continue to shout from the rooftops, it’s much easier to criticize this in the context of today where the immediacy of these cartoons at our disposal allows for us to point out such lazy reuse, whereas a theatergoer in 1939 may consider it odd at best and never think about it ever again. Even then, other directors under the same or similar constraints didn’t use such lazy cribbing, or at least made more hearty attempts to disguise it.

In the end, it doesn’t detract from the sake of the gag (being that Porky summons worms from the ground with the use of a funnel, as though he’s a snake charmer, allowing the chicks to feast), but it certainly is bewildering.

At the very least, the little duckling wanders into the scene—giggles and all—to rid the mustiness. He has his own relatively anticlimactic battle with a stubborn worm, the struggle indicated much more in the music score than the animation itself.

Sent flipping in the air, the worm (touting an anthropomorphic face) allows the duck’s incapacity as a means to escape back into his hole. The drawing of the duck sticking his beak in the hole, his fleshy beak cheeks billowing onto the ground, is the most amusing part of the sequence.

Clampett’s love of cute meets sadistic rides again as the worm shamelessly smacks the duck with a mallet, Blanc’s previous infantile coos and giggles making the impact sting all the harder.

Luckily, the duckling is unscathed, his beak reverberating, accompanied by gibberish sound effects.

“Sold to an American!” The worm recites the catchphrase of the Lucky Strike radio ads, a gag Clampett would get a lot of mileage out of whether it be past (Porky & Daffy) or present (The Wise Quacking Duck.)

From one bit of business to the next, the camera then dissolves to a mother hen rocking her basket full of brethren, clucking a nasally lullaby of “Rock-a-bye Baby”.

Aluminum bangs and popping sound effects distract the mother from her handiwork. Ever so cautiously, she spills the active eggs onto the ground…

…prompting her newborns to hatch out of their eggs and battle with a newfound case of vertigo, said chicks swaying to and fro as they mindlessly cluck their own childish chorus of the lullaby.

“Now isn’t that cute!” At last, one of the farm gags has relevance to the story (if any.) Surprisingly, Danny Webb, not Mel Blanc, is the source of the gravelly snarl from offscreen.

Pan to a hungry fox hiding in the bushes. While Mel Blanc is infinitely talented beyond belief, Danny Webb’s own sinister delivery of “So young… and tender…” adds a nice breath of fresh air in terms of who voices the villain. Blanc’s villainous voices are endlessly amusing, but there’s a certain novelty in hearing someone such as Webb perform his own unique take on the voice.

Though the close-up drawing of the fox envisioning roasted chickens in his eyes is relatively crude, it’s still made amusing by the complete lack of subtlety. The eyelashes and visible caruncles add a certain sinister grotesqueness, perhaps even as an accidental side effect.

“Yum yum!” Shifting back to the full shot of the fox, the background appears to jump slightly before he licks his lips, the animation well constructed and rubbery. The firm construction and slightly floaty but anchored movement possibly suggest this as John Carey’s handiwork.

In a very Tex Averyesque maneuver that unfortunately verges more on unnecessary rather than funny, the fox departs, only to zip back in place and whisper an extra chorus of “Yum yum yum yum yum!”s.

Focus delegates to one of the baby chicks, who shudders beneath the imposing shadow of the fox: “Gee, it’s co-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-ld!”

Once he recognizes the source of the shadow, Clampett grants us with our second Mel Blanc scream gag (which is incredibly hard to grow tired of): “THE FOX!!!”

Clampett gets slightly creative, having the fox ominously slam his paw down on the ground, narrowly avoiding the fleeing chick. Obscuring the fox’s body and face makes his presence seem all the more ominous and dangerous.

Elsewhere, the remaining chicks join in a trembling huddle, including the lone duckling. Mama hen is quick to confiscate her young’uns, leaving the poor duckling to his own devices as the shadow looms over him.

That Clampett utilizes the shadows so often is not taken for granted. While his compositions were seldom incredibly dynamic or intricate, it does seem worth noting that the cartoons he wrote himself or worked on in more than one compartment seem to fare better in the creativity department. A lack of a writer’s credit here infers that he storyboarded the cartoon himself. A Tale of Two Kitties had Clampett doing layouts himself, the staging in that cartoon comparatively drastic and stressing height differences often.

Indeed, Porky’s shadow here projected onto the wall aligns with the heavy emphasis on silhouettes in the beginning of Kitty Kornered, which Clampett also wrote. Correlation is not causation, but the correlation is certainly an interesting talking point.

Armed with a comically oversized axe, Porky launches into battle. However, the fox comes prepared; rather than whipping out his own axe or baring his fangs, the blunt approach is the best bet as he wastes little time pulling out a rifle.

Rather than aiming explicitly at Porky, the gunfire is directed towards his axe. As Porky charges, the axe is cloaked behind a cloud of smoke. He skids to a halt, waiting for the bullets to subside…

The grand reveal is definitely on par for Clampett’s sense of humor, who particularly enjoyed playing around with size disparity.

Meanwhile, the duckling’s shrill cries for help are overheard by his mother, happily swimming along in the pond. She halts, pausing to count her babies, each marked with quacks that instantly resemble numbers.

It seems that Bob Clampett is the voice of the mama duck; he’d voice the mama duck in Wise Quacks, as well as supplying the vocal quacks in cartoons such as Porky’s Poppa and A Corny Concerto. Aside from Tex Avery, it was pretty rare for directors to provide voices in their own cartoons, always a treat through the sheer novelty of it all.

Mama counts four ducks and five fingers, the disparity between five fingers on one hand and four on the other relatively amusing. The animation as a whole is pretty crude, whether the result of poor animator draftsmanship or poor assistant work and inking. Particularly noticeable when the mama duck pauses to think, her features seem to jostle and float around.

Nevertheless, her hysteria is very clearly conveyed through frantic quacking and spastic movements, jumping up in the water and searching beneath her babies, as though her missing duckling was hiding beneath them.

When all else fails, a call to arms using her beak as a bugle. Here, the mama and her babies take off like fighter jets, scouring the ground for any sign of the missing duckling.

Back to the fox, holding the duck hostage with his rifle. His sneers of “Stand back!” sound like the vocal work of Mel Blanc rather than Danny Webb, a seemingly semi-common occurrence.

In any case, the mama duck is able to track down the culprit, signaling for her babies to follow her lead as she swoops down below. The foreboding cacophony of droning jets prompts the fox to escape in a frenzy. As was the case with obscuring the fox as he initially tracked his victims, hiding the ducks offscreen and using sound effects as the only indication of their presence heightens the stakes and makes the pursuit seem more dangerous than it really is.

Likewise, the opposite applies when the fox rams himself into a tree, the ducks pecking at him as he recovers. Stiff, mechanical, and too evenly spaced, the animation suffers and makes the pecks appear much more comical and light rather than posing as any sort of threat.

Regardless, that too is rectified when the fox aims to attack the source; Porky, second banana in his own cartoon, briefly puts up his dukes before getting a repeated mouthful of fists and ducks.

Inanimate objects to the rescue. Here, the baby ducks who seem to have doubled in size, drop a spare dress cage upon the fox as though it were a bomb. Indeed, the cage entangles itself around the fox, Clampett making the most out of the dress’ slender physique for the sake of a visual gag; a much more playful choice than a roll of chicken wire or any other similar alternative.

Enter the real bomb, a giant canister of TNT. As the ducks drop it below, Porky wises up, scrambling to grab ahold of the baby duck sitting on the ground. Once more does Clampett tap into the realm of scrambles, double takes, any sort of delay or imperfection that continue to ground Porky and make him seem more sympathetic through such realistic actions.

Skidding diagonally into the foreground adds a strong sense of depth, much more impactful than a standard horizontal skid from left to right. It further allows the audience to view the relieved actions from both Porky and the duckling more clearly.

As for the fox, Clampett doesn’t skirt around the bush at all. In fact, he obliterates it. The fox dies right onscreen as the bomb drops and explodes, throwing both the bomb and fox up into the air.

While the fox’s corpse remains in the sky, waiting to come back down, the camera makes a not so subtle pan left to account for the coming payoff:

A fresh fox fur, price tag and all, is conveniently draped on top of the dress cage that lands on top of a nearby tree. With no other fanfare, we iris out, a non-ending to a non-cartoon.

As previously mentioned, Chicken Jitters’ biggest problem isn’t that it’s bad. It’s that it isn’t anything at all. There’s hardly any reason as to why this is a Porky cartoon (other than contractual obligations); had one swapped this out with, say, Buddy—heaven forbid!—the premise and characterization would be the exact same. Here, Porky is a nonentity, included purely to appease the contract. There isn’t even a reunion scene towards the end where he reunites the mama duckling with the baby as he does in Porky’s Poultry Plant or Wise Quacks, this cartoon taking inspiration from both (or, rather, the latter taking inspiration from this one.)

This is indeed Clampett at his worst, and that says a lot—if being at one’s worst is mindlessly mediocre, that’s quite the achievement. Not many directors can say the same. Some directors can’t even reach mindlessly mediocre at their best. So, for the biggest sin of this cartoon to be its startling unremarkability, that’s still by all means something worth commending.

Carl Stalling’s music score is undoubtedly the biggest attraction of the cartoon, often a saving grace for most cartoons of this variety. It’s fun, it’s chipper, it makes for easy listening. Some of the backgrounds are nice, particularly the opening with the vines framing the rooster on the fence, and the use of shadows during the climax is a creative approach.

Regardless, these are all gags that have been seen before, or at least retooled to greater lengths, even by 1939’s standards. There’s very little coherence in the story because there’s nothing to provide that coherence to begin with. Any sort of story present takes 4 and a half minutes to get to, whereas the cartoon itself, not counting titles and outros, only clocks out at about 6 minutes and two seconds. Meanwhile, animation reuse is not and should not be a sin, but rather, how well it’s applied; Clampett’s application (or lack thereof) of the scene from Porky’s Poultry Plant is an excellent example of what not to do when recycling animation.

There’s no real reason to discourage anyone from watching it, but there’s absolutely no reason to encourage anyone to watch it, either. It’s a cartoon at its barest essentials: 6 minutes of animation with music, sound effects, and sometimes dialogue behind it. Very little else.

In any case, enjoy! The cartoon is also available on HBO Max.

No comments:

Post a Comment