Release Date: April 8th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Rod Scribner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Butch, Fly, Warden, Prisoners, Oscar, Barber) Danny Webb (Guards, Lug, Whistle)

After working at the studio for 4 years, joining as an assistant animator in 1935, Rod Scribner is finally graced with his first animation credit.

Scribner is one of the most common names thrown around by animation historians for incredibly good reason. It’s no stretch of the imagination to deem him as the wildest animator of the studio and possibly one of the wildest animators during the golden age of animation as a whole.

Most commonly associated with his work under the direction of Bob Clampett, Scribner animated for Chuck Jones and the Hardaway/Dalton unit before heading over to Tex Avery’s unit. Bob Clampett later inherited him in 1941 after Avery’s departure, and it’s there where he did his most iconic work. Evidently, he animated his work with ink rather than pencil, proving to be a hassle for the ink and paint department when trying to figure out which brushy lines to trace. Comic artist George Lichty served as a big inspiration for Scribner, and Clampett would often encourage Scribner to “Lichty this a little” to squeeze the best work out of him. Indeed, Scribner’s animation was at its most hectic, elastic, and frenzied when under Clampett's direction.

|

| Rod Scribner and Manny Gould in the Clampett unit, 1945. |

After Clampett left the studio in 1945, Scribner was assigned to Bob McKimson’s unit, where he would remain there all the way until the studio shutdown in 1953. A bout of tuberculosis in 1945 put him in the hospital for three years, making his return to the unit in 1948; tuberculosis would also play a part in his death in 1976.

For all of his extreme talent, Scribner had his hardships. He battled with severe mental illness, floating around hospitals, getting arrested, and drug use exacerbating his TB. Later in life, he couldn’t recall his tenure at Looney Tunes, and his footage for Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat was deemed unusable, with him having to walk out of the studio. He was a brilliant man who was misunderstood (Bob McKimson keeping such a tight reign on his work very well may have been catalytic towards his decline, but that’s a discussion for another time), which made for a very lonely and depressing end.

Nevertheless, his work deserves to be celebrated rather than pitied. Even in a 1939 Hardaway cartoon, his eccentric drawing style is incredibly easy to pick out and a leap above the rest in terms of energy and caricature. Here, gags are explored pertaining to the prisoners of Alcarazz Prison.

That the cartoon opens to a moody shot of an isolated prison, orange morning sunlight mingling with tendrils of fog, bluesy muted saxophone music score in the background, is an encouraging sign. No unnecessary dialogue, no unnecessary puns; only atmosphere.

That is, no unnecessary puns just yet. Trucking into the prison prompts a dissolve to the entrance. In pure Hardaway fashion, the still shot of the entrance winds up to the joke, a sign acknowledging “STONE WALLS DO NOT A PRISON MAKE”…

Pan out to the reveal of “BUT THEY SURE HELP!”, a reference to Richard Lovelace’s “To Althea, from Prison”: Stone walls do not a prison make, nor iron bars a cage; minds innocent and quiet take that for an hermitage.

It’s corny, but the truck out and reveal helps. A pan down rather than out may help maintain the momentum and allow the joke to land harder, the truck-out a little slow in its delivery, but any sort of camera movement is welcome as opposed to a still shot of both the exposition and punchline.

Elsewhere, more corny gags, such as a clock with a ball and chain pendulum, the time a variety of decades (and it certainly is oddly grounding to see the 2020s included on the clock face), as well as a stack of pardons included in a “TAKE ONE” box.

A camera pan right allows room for snoring gags as the prisoners wake up, particularly the cell doors slamming open and closed, spinning on their axes, as well as a ball and chain blowing back and forth between two bunk mates.

Said ball smacks the lower bunk mate in the face, which promptly wakes him up. He retaliates with a punch…

…and gets a slam dunk. Not laugh out loud funny, but surprisingly to the point; that there hasn’t been a line of dialogue a minute into this cartoon is a feat in itself. The pennant on the wall advertising Sing Sing prison as though it were a college works well enough to stress the immaturity and mischief inevitable to come.

Meanwhile, a fly makes its way into the cell of another prisoner’s, who eyes it contemptuously. Rather than getting up to swat at it, he remains in bed, moving to only his eye as he tracks its movements.

With the fly landing on his feet, the prisoner uses it as an opportunity to make the kill. The camera panning into the fly upon impact adds an elevated sense of urgency, a spotlight on the fly’s entrapment, even if the pan itself is a little slow to warrant any true sense of alarm.

In any case, the main sake of the truck in is to shift focus onto the fly’s manly Mel Blanc shriek of “OUCH!!!” Like any and all Mel Blanc yells, the echo of the soundstage in which Blanc recorded in does wonders to make the scream seem more vast, loud, and, most importantly, funny.

With prisons come prison breaks. Here, a rather unassuming dog touting some baggy clothes, stressing his incompetence and that he’s too small to fit his own role, unsuccessfully makes an attempt to escape by filing the bars.

Little acknowledgement of the gag’s absurdity works, miraculously, in Hardaway and Dalton’s favor as the dog steps out of the bars with little issue, attempting to file them down from a different angle.

Perhaps even better is when he gets caught by a nearby guard; rather than diving back into the sanctity of his cell, the dog leans against it from the outside, filing his gloved hands inconspicuously. There are no attempts to usher him back inside or chastise him for being outside of the cell’s limits. Such nonchalance is a miraculous feat in a Hardaway and Dalton cartoon—a shame that it wasn’t always the case.

Meanwhile, another prisoner enters from stage right who has grown into his clothes and his role, judging by his grisly five-o’-clock shadow, hulking physique, and audacity to stick his tongue out at the guard.

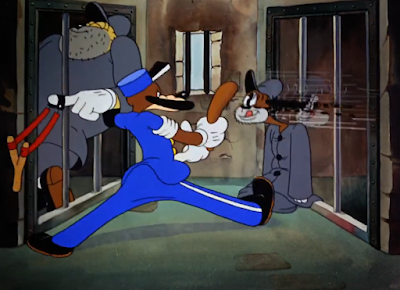

No confrontation is given. Instead, the guard marches along on his floaty, awkwardly animated way, any sort of weight in his walk conveyed purely through Carl Stalling’s lumbering music score. As such, the bigger prisoner (who is referred to later as Butch in a song number) opts to have some fun, retrieving a slingshot and shooting a spare bolt in the guard’s direction.

Another encouraging sign is that the impact occurs offscreen. Hardaway and Dalton don’t cut to a bloated reaction shot of the guard getting hit; the audience’s only context clues are the dull “PAP!” offscreen and the anxious reaction from the smaller prisoner.

“Who dun that?” Danny Webb voices the guard, cutting off Butch’s inconspicuous whistling as he very visibly flicks the slingshot around on his finger. His lackey, on the other hand, continues to file his gloves.

Yet another mark of success is the coming gag. Rather than smacking Butch, with his slingshot in plain sight, the guard wallops the lackey, whose only crime is escape, not slingshotting.

While striking the wrong offender isn’t exactly funny in itself, what IS funny (once more to the miraculous credit of Hardaway and Dalton) is the execution. The impact is curt, swift, and subtle; the guard is eyeing Butch down the entire time, his body facing that direction. There are no visible clues that the guard is about to disobey his trajectory and pull a fast one on the audience. The hit does genuinely come as a surprise, which is something worth celebrating in the H/D efforts. Seldom do their efforts at a surprise actually take.

While the animation does suffer, the lackey slumping in a daze and his head springing back and forth feeling wooden and mechanical, the spirit of the gag is what prevails. The execution was just strong enough that the animation doesn’t have to serve as a saving grace. For once, the gag comes out on top.

Enter one Warden Paws, a double caricature; caricature of prison warden Lewis E. Lawes in term of namesake, caricature of Hugh Hubert in terms of vocal stylings.

Animated by Volney White, the warden’s poses feel incredibly Tashlinesque (seeing as he animated under Frank Tashlin), silhouettes strong, lines of action exceedingly clear, and even the rubbery, bulbous physique harkening back to Tashlin’s design sense. A jaunty calliope score of “The Umbrella Man” accompanies the warden’s nonsensical yet muted ramblings, the music indicating a few screws are loose.

Indeed, the warden’s dialogue, expertly performed by Blanc, confirms as such: “Hoo hoo hoo! Wonderful morning. Wonderful morning. Great morning. Fine day. Wonderful morning. Hah.” He opens the door from his office as unconventionally as possible, sliding it upwards like a curtain and then sideways.

“Hoo hoo! Just said that, didn’t I? Hoo hoo hoo hoo! Fine morning.” For once, the Hardawayian tendency to include interminable, monotonous dialogue pays off as the warden attends to his daily duties, rambling all the while.

“Time to get up now. Gotta get ‘em up.” Beautiful posing from White as the warden gently tinkles a tiny bronze bell in front of the jail cells. “Hoo hoo hoo! Gettin’ late!”

“Can’t sleep all day, you know. No no no. Ha! Can’t sleep all day! No no—hoo! I don’t sleep all day myself. Hoo hoo hoo! Insomnia. Hoo hoo hoo hoo!”

Segue to an escapee, who gets to the source with a shovel, digging a considerable sized hole in the cell floor. Staging the shot so that the dirt covers the foreground adds more depth to the composition, without having to rely on any sort of intricate perspective for the characters themselves.

As such, standard but effective cartoon staging prevails when the warden pokes his head into the cell, the escapee posing innocuously on his bed.

“Mice.” Short, sweet, to the point. No unnecessary questions or rambling dialogue.

Rambling dialogue is delegated to the warden, who continues on his Hugh Hubertesque ranting, hoo hoos now a symbol of anxiety rather than jubilation. Here, he paces back and forth, muttering about how they need to get a handle on the mouse problem.

“I’ll have those mice paroled. Hoo hoo hoo hoo!”

Interestingly, a diagonal screen wipe is used as the transition to the next scene, rather than a dissolve or iris wipe. Transitions such as irises or diagonal wipes call more attention to themselves, rooted in their playfulness and unconventionality. Not only that, but they also serve as reminders of the transitions and mechanics utilized in silent films, whose influence permeates nearly every aspect of these cartoons.

Hardawayisms leech their way back into a shot of a prisoner waking up in his cell, particularly the sign on the wall that reads “A MAN MAY BE DOWN BUT HE’S NEVER OUT! — The Warden”. Much like the opening, the prisoner here also has college-esque pennants adorning his cell.

Voiced by Danny Webb, the prisoner is considerably chipper, lumbering over to his birdcage. Said bird is a literal jailbird, much like the one in Tex Avery’s A Day at the Zoo.

Webb’s vocals here are perky to a disconcerting degree. “Good morning, Oscar!”

“Hi, lug.” Gravelly Mel Blanc vocals from the bird ensue.

Content with the interaction, said “lug” directs his attention to the window. While the double exposure of the sunlight causes some problems on the body of the prisoner, the blur sparking a delayed, almost dreamlike motion as he moves, the animation of the sunlight pouring through the blinds is surprisingly well executed.

“Just get a load a’ that sea air!”

Similar to the captain’s rude awakening in Porky the Gob, the prisoner is greeted with a hearty dose of salt water right in the face. Though the delivery of the water is sluggish, it fares better than the spray in Gob, the inclusion of color likely helping to add a little more weight and differentiation to the water. The lack of any reaction from the prisoner also helps immensely—no dubious blinks or belabored scene of him coughing up a fish.

From one gag to another, the camera jumps to one of the prisoners brushing his teeth over the sink.

Correction: tooth. (Note the "tooth goo" as opposed to toothpaste.)

Yet another diagonal wipe brings possibly the most brilliant moment of Hardaway and Dalton’s career; not exactly for the payoff, but the execution—no pun intended.

Certain poses of the characters aren’t the only Tashlinesque aspect of the cartoon. Broadcasting the shadows of a prisoner being dragged to his death via execution is a very creative and bewilderingly competent choice; surprisingly, the shadows are well constructed, warping and snaking around the walls at intricate angles as the camera continues to pan ominously—not just a flat, single shot of a wall. The perspective is impressive by any standards, but particularly for Hardaway and Dalton’s. They’re genuinely comparable to Tashlin’s silhouette work in Little Beau Porky.

Not only is it artsy; it’s sinister. As mentioned in our review of Chicken Jitters, utilizing shadows to obscure the action provides a heightened sense of urgency, secrecy, fear—that is, fear of the unknown. Perhaps the only thing more horrifying than a man being dragged to the electric chair is deliberately dangling the threat over the audience’s heads and teasing them with mere shadows, the act itself up to the active imagination of the viewer.

Not only is the escort concealed, but the act itself. The ominous threat reaches a chilling crescendo when met with the shadow of a guard flipping the switch.

Most chilling of all, however, is the shot of the lights in the jail dimming, accompanied only by the foreboding buzz of the electric chair as it uses up the entire energy of the prison. Hardaway and Dalton never have and never will get this creative again.

Such is evidenced by the reveal of the gag itself, very much in line with the gag sense of Hardaway and Dalton but excusable for the arduous buildup alone. Rather than getting an execution, the prisoner is met with a shave and a bowl cut—a fate worse than death.

Mel Blanc voices the stereotypical Italian barber. “You sure got-a tough-a whiskers-a, buddy!”

While a variety of prisoners have been displayed so far, the frequent cutting to the escapee-in-training and his hulking, grizzly companion indicate they’re characters to keep an eye on. Indeed, the juxtaposition in their attitudes alone is amusing, not only in their outward appearance but the way they perform their duties. Whereas the little dog dutifully scrubs the floor, Butch haphazardly sweeps the floor by barely moving the mop an inch, maintaining the same, painfully disinterested expression all the while. That, paired with Stalling’s sleepy, sardonic music score of “Monday Morning” make for a wonderful pairing.

Suddenly, Butch grows laborious. His mopping is purely good behavior; the guard from before struts back into frame, surveying them both with a stink eye. While the constantly moving motion of the guard is slightly distracting, the shift in tone from Butch is strong and amusing enough to pardon any insufficient animation from a character who only graces the scene for a second.

Ensuring that the guard is out of earshot, Butch sneers to his lackey. “Watch ‘dis!”

SPLAT! Cut to a shot of the guard being met with a mouthful of mop. He turns very briefly at the last minute, as though to indicate he’s constantly on guard when one least expects it, but it very clearly comes off as a vehicle for him to get hit in the face. While the wind-up is a little too deliberate and stretched out, the intent is nevertheless clear.

“Who threw that?” The guard rephrases his earlier query when Butch nailed him with the screw. Innocuous whistling proves him innocent.

At least until he rolls up his sleeve, growling “Who wants ta know?”

Unlike the earlier confrontation, the guard smacking the innocent lackey suffers from being too deliberate and drawn out in its execution to be a surprise, especially considering the audience is now acquainted with the gag. Though it is the correct route to go (running gags are always fun to see, and having the guard dismiss the two would be too unsatisfying), the execution is pivotal to the impact of the hit, which isn’t as strong as what was displayed in the previous scene. Nevertheless, continuity is the priority over execution.

Rather than having the prisoner’s head wobble back and forth, his body reverberates instead, thanks to the guard having him in a chokehold. It’s only when he lets go and attends to his guard duties that the lackey’s head is free to wobble as it pleases.

“Why dont’cha bounce dat ball off his dome?”

By the power of suggestion, the mute lackey obeys orders. One gets the sense that physical violence would ensue had he done otherwise.

Gil Turner animates the lackey approaching the guard, his handiwork noticeable in the timing and gliding, glacial movement of the animation. To Turner’s credit, the pose of the lackey aiming to throw the ball is strong in its line of action, the excessive detail on his snarling, funny teeth more funny than disconcerting.

When caught by the guard, he cues the innocent act, playing with the ball like a schoolboy. For once, the chronic weightlessness of Turner’s animation seems to work to the gag’s favor, as though working in conjunction with the transformation of a cruel hinderance to schoolyard toy.

“Drop that ball!”

Mild manners prevail. The lackey tosses the ball behind him…

…before recalling the phrase “ball and chain”. Creating a gaping hole in the floor, the weight of the ball is quick to drag the poor soul in with him. Turner’s animation is slow with too many drawings, the impact losing its punch, but the general joke is conveyed clearly and succinctly.

Wipe to lunchtime in the mess hall. Though the drawings are merely mirrored on either side of the cafeteria, keeping track of that many characters all having to eat and chew their food at that small of a distance is quite a feat. Major props to the ink and paint department. Symmetrical staging unifies the animation, allowing for stronger coherence.

Butch is the center of attention yet again, this time grinning as he sneaks furtive glances. A pronounced lower lip indicate smugness, mischief; a plan is surely being hatched.

His tough man status is firmly established as he bites a corn cob in half with little trouble. Rod Scribner’s handiwork is immediately recognizable in the prominent, solid teeth and pronounced wrinkles in Butch’s scowl.

One hushed whisper of “Two o’clock!” sparks 8 of them, each call to arms following a rolling momentum as the camera pans through all of the scheming prisoners. That the only pause is delegated towards the first prisoner catching wind of the plan is a breath of fresh air.

In fact, the rhythm of the sequence is so strong that even the little escapee-wannabe gets entangled in its flow, accidentally spoiling his plans to the guard at the end of the table.

Shot on ones, Scribner’s wild take is difficult to digest unless paused, but serves as a visual treat to the eyes. It works quite well in motion, allowing for a very quick pop of realization that accurately reflects the startled prisoner’s emotions.

Fearing another clobbering, the prisoner is quick to use a tin bowl as refuge, shielding himself from any and all potential blows.

Nothing. Though his gradual relief isn’t gradual enough, the reaction time a little too quick to allow his trepidation to really sink in, his fears are nevertheless realized as the guard clobbers him with a nightstick after the prisoner removes his bowl-turned-shield.

Head wobbles resume.

With that, the clock strikes two, marked by exaggerated (for 1939 Hardaway/Dalton standards) expanding and contracting clock ringing cycles, as though each chime of a bell requires a particularly strong exertion of energy.

A rather bloated, floaty cycle of gunfire explodes right on the dot. The payoff of the gag could stand to be twice as fast to further stress such an abrupt change, but, as is our theme with this cartoon and many others, the overall idea is there.

Focus then shifts into the song number, yet another highlight of the cartoon. Sung in the music stylings of entertainer Jerry Colonna (who would soon become a regular in the never ending repertoire of caricatures in Warner Bros cartoons), the musical is a stronger testament to the talents of Mel Blanc and Carl Stalling rather than the directorial skills of Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton.

Here, Butch sings an ode about his desire to break out of prison, here set to the tune of “Daydreaming”. Though the animation isn’t exactly appealing, Blanc’s vocals are filled with as much charm as they possibly can be under the direction of Hardaway and Dalton.

The fake out with Butch pretending to be sleepwalking when he’s confronted by the guards is amusing, especially in conjunction with the lyrics (“All night long I’ve been dreaming and scheming a way to escape; the warden and guards, they all bore me—life in prison was never meant for me!”

Rod Scribner appears to animate Butch’s send off to his “loving buddies”, present in the gummy, prominent teeth and tall, slightly misshapen eyes. The same applies to the close-up of Butch eyeing the locked up guards behind bars. Elsewhere, Gil Turner is responsible for Butch’s cuddling up to the warden, identifiable by the constant head tilts and slow, floaty animation style.

The crux of the song comes down to a gorgeous, sardonically sappy piano rallentando from Carl Stalling in conjunction with Blanc’s accented “So ve-ry, ve-ry, ve-ry, sorry, warden de-ahh!” Colonna impression or not, Blanc’s rolled tongue adds a comedic insincerity to Butch’s graceful ballet dancing and cooing. No inmates complain about his being free and not themselves. The warden doesn’t make any attempts to stop him. Spellbound by the power of music; the faux-saccharinity works wonders. The entire sequence almost feels comparable to a Mel Brooks number.

After a call and response section between Butch and one of the guards playing his gun like a flute, music suspended save for the flute to place emphasis on the duet, Butch makes his grand departure: “GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOD-UH… BYYYYYYYYYYYEEEEEEEEEEEeeeeeeeeEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!!”

Pausing to shake the warden’s hand, vocals a victim of the doppler effect as they grow louder and softer, is pure genius.

Excellent comedic timing with the warden’s amiable response of “Hoo hoo! Bye bye.”

After giggling about the possibilities of Butch’s voice, realization strikes that a jailbreak is underway. Herman Cohen animates a close up of the warden mumbling about how someone needs to do something, animation well constructed but muddled by constant motion and little variety in its spacing.

After coming to the bright conclusion of “Say, that’s a good idea. Maybe I can do something. Sure! Hoo hoo!”, he blows into his whistle.

No dice. Just the hollow sound of hot air.

Typical Hardaway gag sense ensues as the warden takes the whistle out of his mouth, the whistle working only then. Befuddled blinks that take too long are also a must—the gag, as always, takes a little too long to be delivered. Hardaway and Dalton have a knack for balancing a high point with a low point right after.

In any case, attempts to be theatrical ensue, again interrupted by the corniness of a whistle blowing with poorly directed Blancanese. Staging the angles of a gunman and the whistle at a slight diagonal angle add some much needed dynamism, diagonal angles typically indicating action or movement. A quick cut to the whistle and the short length of the shots furthers the urgency.

No jailbreak is complete without a motorcade. The showdown parallels a similar climax in Friz Freleng’s I’m a Big Shot Now, primarily from the police shooting at the prisoner’s hideout, said prisoner shooting out the window, and even shooting all of the hats off of a line of policemen. In a rare reversal, the Hardaway climax is much shorter and to the point, which certainly works in its favor.

One of the most inspired bits of action comes from an officer firing bullets into the gutter of the hideout. With Butch taking refuge in a bathtub, the bullets rise up the gutter and fire out of the shower head. The scream of “OUCH!” sounds as though it may be reused from the fly’s own scream at the beginning of the cartoon.

Nevertheless, in an attempt to escape, Butch seeks refuge in a chimney. Little time is wasted shooting that to pieces as well.

Right before he falls in the police car, getting cobbled by a swarm of nightsticks (yet another parallel to I’m a Big Shot Now), the poses of Butch struggling to keep his balance are incredibly strong for H/D standards. Clear silhouettes, strong lines of action, overall streamlined design.

And, once more similarly to Big Shot, the camera dissolved to Butch back in jail, locks liberally draping the door of his cell. Pan out to reveal the little lackey from before still dutifully scrubbing away at the floor, Stalling’s lazy accompaniment of “Monday Morning” a representation of Butch’s defeat and a nice bookend to his cleaning duties from earlier.

To further the bookend, the guard from before struts back into scene, sneering with some awkwardly timed but nevertheless amusing grins towards Butch and his lackey.

Old habits die hard. Just as the guard is out of sight, Butch smacks him upside the head with a nightstick of his own, likely purloined from one of the coppers during his escape.

Lackey knows what to do. In conjunction with an orchestral fanfare, he snags the nightstick out of the copper’s grip…

SMACK! Iris out on a dazed lackey and his not-so-innocent accomplice.

Of all of the Hardaway and Dalton entries, Bars and Stripes Forever is my personal favorite and one of the better cartoons of their filmography, if not best. It is still very much a cartoon supervised by Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton, and isn’t exactly a masterpiece or even worthy of the title “great”. Hardawayisms still pepper the cartoon; corny gags, some of which revert back to the same insufferable sluggish pacing that kills any beginnings of a potentially amusing joke, at times awkward voice direction, aimless movement in certain scenes, relatively unappealing characters designs, and so forth. There are times where one can almost physically feel Hardaway and Dalton struggling to drag the cartoon back to their own realm and bad habits.

Nevertheless, these issues that pepper the H/D cartoons in droves are comparatively sparse in a surprising twist. Many times, the execution of the gags is what makes or breaks the deal. Here, the execution of certain gags fare particularly well. The electric chair scene has a corny payoff, but the buildup is sublime, whether it be the perspective of the shadows on the wall, Blanc’s pleas to live, Stalling’s foreboding dirgelike music, or the decision to obscure the gruesome action and leave it up to the imagination of the audience.

Perhaps it has something to do with Jack Miller’s story credit—this is his first credit for a H/D cartoon. Seeing as he wrote greats such as Hamateur Night, Thugs with Dirty Mugs, You Ought to Be in Pictures and Pigs in a Polka, his addition bringing a higher precedent of quality isn’t some unfounded theory.

Nevertheless, by whatever miracle, what worked worked well. Blanc makes the best of the limited ability of the vocal direction; Butch’s song number is genuinely catchy, and the warden’s ramblings serve as an indulgence to the Hardawayian tendency of excessive dialogue, but, with that being the joke, works well in this occasion. Danny Webb as the all-too-eager prisoner getting sprayed by the ocean is equally amusing. Stalling’s music score is excellent as ever and elevates any weaker scenes by providing as much ambience as possible.

Sadly, Hardaway and Dalton do not climb an upward hill of improving quality after this. And, as mentioned previously, this cartoon is still indeed present with a number of problems that litter the H/D cartoons, and isn’t a great short by any means. Yet, for Hardaway and Dalton, any success is worth celebrating and investigating.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment