Release Date: March 25th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Cuckoo Bird, Curious Puppies)

After almost a year of stagnation, the prototype Bugs Bunny makes his second ever appearance, this time under the direction of Chuck Jones.

While the proto-Bugs while always here removed from his future self, certain traits and motifs—whether it be participating in a magician’s act or remaining confident in his heckling—are birthed here that would later be tacked onto the real thing.

Here, Jones brings back his two curious puppies, this time pinning them against the screwball rabbit as they seek shelter in an abandoned house once occupied by a magician. The magician’s old acts remain in the house, stirring up trouble for the puppies—particularly when they come across the magician’s rabbit.

Unlike Jones’ previous handful of cartoons, little time is wasted getting down to the action. The cartoon opens to a shot of a dog catcher’s truck speeding—at least, by Jones’ standards—down a country road in the night. Already, the silhouette of the dog catcher, the frown and glare on his profile visible, speaks to Jones’ artistic sensibilities, reading as something he would polish and refine in later years.

A pan of the camera left reveals the victims of the dog catcher: the curious puppies of Dog Gone Modern fame. The chase is glacial at best, but elevated by Stalling’s frantic musical accompaniment and Art Loomer’s moody nighttime backgrounds.

Indeed, mood is rife in a shot of the dogs seeking refuge in an old, abandoned house nearby. The colors are vibrant, a warmth permeating from the cool color scheme, highlights and shadows particularly prominent thanks to the glow of the full moon illuminating the backs of the trees and the house. Loomer’s background work can have a tendency to get a little loose at times, feeling more akin to a painting rather than a cartoon background, but the atmosphere is firm and the colors, values, and lighting are certainly inviting.

A quick pan left allows more room for the camera to track the dog catcher, who continues to wind down the country road. Aforementioned loose brushwork is more prevalent in this shot, the trees and grass reading more as blobs of paint.

Nevertheless, the camera pans back and trucks into the front porch of the house, revealed to be the home of Sham-Fu the Magician thanks to a not so subtle sign in the doorway. The curious puppies are cautiously optimistic at having abandoned their pursuer.

That is, until a door springs open behind them, the pressure plate beneath them launching the pups into the house. The composition of the scene is simple but strong, the wooden walls on the porch framing the pups and unifying the action through symmetry. Physics on the door and pressure plate also possess the adequate amount of elasticity required for their respective motions.

Animation of the pups sliding across the entryway and knocking into the wall would have been thrice has fast had the cartoon been made 2-3 years afterwards. Though, sluggish as it may be, it does provide ample time for the audience to admire the interior of the house and the composition of the scene therein—a crest with a wolf’s head and double swords, an owl on the staircase banister, paintings, masks, cobwebs, etc. Much like the walls on the porch, the stairway serves as a nice method of splitting the screen in half and directing the viewer’s eye to the puppies on the floor.

With any abandoned magician’s house comes a cuckoo clock, always raring to greet visitors. With cape hugging villains on the mind thanks to Porky’s Movie Mystery, the cuckoo bird joins in on the fun, sneaky looks fast and snappy and purposefully indiscreet.

“It’s twelve o’ clock!” Mel Blanc provides the bird’s ominous message, followed up by villainous cackling. The departing wink is a particularly playful touch that also foreshadows any and all whimsical antics that lie ahead.

Rod Scribner takes over the animation reigns, animating a rather lengthy portion of the cartoon at almost a minute. Though his animation earmarks grow more apparent as the scene progresses, trademarks of his style eke their way into the pups—particularly when the Boxer pup collided into an empty wall where his companion has been swallowed, wide eyed and wrinkles conveying the Boxer’s stupefaction.

“Pssst!” A voice offscreen interrupts the pooch’s search, sniffing the wall and shaking his head. While Prest-O is no car chase either, the pacing already fares considerably next to Dog Gone Modern. The investigation of the mysteriously disappearing entryway would likely have taken twice as long in the aforementioned cartoon.

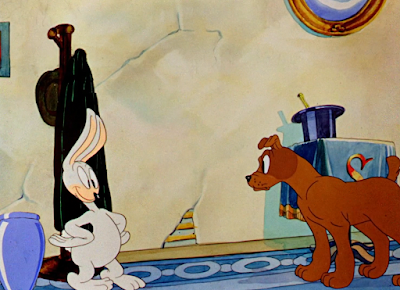

Enter one prototype Bugs Bunny, the culprit behind the offscreen “psssst!”ing. Changing hands from Ben Hardaway to Chuck Jones enabled very few changes, but changes worth noting. For one, Bugs (for simplicity’s sake, he’ll be addressed as Bugs in these dissections, much like the case with proto-Fudd as Elmer. For new readers or those unaware, Bugs was never called “Happy Rabbit” as Mel Blanc later claimed; early model sheets label him as Bugs’ bunny, plural, a reference to Ben “Bugs” Hardaway) now has a tan muzzle, a smaller head, longer neck, and a more tall, slender, rubbery physique as a whole.

Though his screwball heckling and strong lack of charisma remain the same, Jones at least arms himself with the gift of (comparative) subtlety, something not present in Hardaway’s vocabulary. Pantomime favors both Jones and the bunny, with dialogue sparse. Here, Bugs serves as the ever faithful magician’s rabbit (something Jones would revisit with the real Bugs in Case of the Missing Hare), showcasing his magic tricks off to a nonplussed Boxer puppy.

First up, a vase. Bugs spins the vase in the air, displays it to the hound, and flicks it to ensure that yes, there is indeed sound emanating off the physical object.

The silhouette as Bugs proudly poses with his prized possessions is particularly strong.

Prest-o! With a few wrist flicks, Bugs compresses the vase in his hands, aided by a descending violin string sound effect from Treg Brown.

Scribner’s animation has a nice popping, snappy effect to it. While still slow in the stranglehold of early Jones’ molasses timing, such a long sequence is at least made more enjoyable by appealing drawings, poses, and music, a jolly score of “The Umbrella Man” serving as appropriate accompaniment—the first usage of a Stalling favorite.

A mildly confused shrug from Bugs is mimicked by a clearly bewildered Boxer. The tall eyes and large pupils paired with the mouth foreshadow Scribner’s facial expressions and trademarks in his work for the likes of Tex Avery and Bob Clampett.

Mimicking continues, with Bugs peering in the Boxer’s ear and vice versa.

Bugs doing a take in regards to something off-screen very well could be the most Scribneresque Scribner gets in Jones’ cartoons. Though mainly visible through the utilization of freeze framing, the timing of the reaction—shot on ones—provides a nice strong pop to Bugs’ movements.

A burst of magic lightning zaps causes the vase to plummet (really, glide at a leisurely place) onto the Boxer’s head. Now, the spacing of the drawings even out considerably, allowing for a glacial, gliding, slow effect on screen.

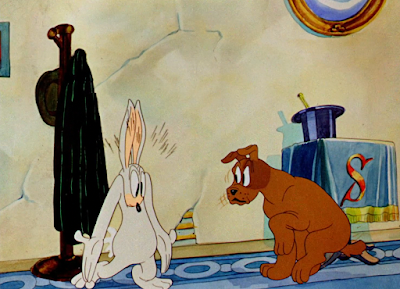

Though one can take the bunny out of Hardaway, one can’t take the Hardaway out of the bunny—yet. Bugs erupts into the same, hayseed, cornball, guttural fit of laughter that littered Porky’s Hare Hunt at every corner. Though Bugs is easier to take here in Prest-O thanks to no dialogue other than laughter, he’s still a very grating, unappealing character, the charm of what made Daffy so charismatic in Porky’s Duck Hunt completely absent in Bugs, said absence still engrained in his DNA. Jones’ more subtle approach works to his favor here, but there’s no comparing the prototype rabbit to the real thing in terms of who's better.

In any case, Bugs is quick to point at the down-and-out Boxer, click his heels and take refuge in the cape he came out of hanging on the hat stand.

Once again, Scribner’s drawing style grows more apparent particularly when the dog growls at his heckler, the gummy, pronounced teeth a trademark of Scribner’s later work.

With that, we segue back to the more Plutoesque tone present in Dog Gone Modern with a lobster attaching itself to the pooch’s nose, causing him to whine and howl and shake his head.

Dissolve to the littlest puppy, stumbling upon a box labeled “HINDU ROPE TRICK” in the hallway. Stalling’s music score melts from jovial to curious, mysterious as the pup investigates the box, his sniffing prompting the crate to open on its own. Curious head tilts and tail smacks against the ground cling to the Disney philosophy of cutesy, lifelike antics.

Enter one anthropomorphic rope. Though the pacing is sluggish, the poses are appealing, particularly when the puppy arches his back while ogling at the rope. The anthropomorphic action of the rope is to be complimented as well—when the pooch salutes the rope in greeting, much like he did in Dog Gone Modern, the rope’s saluted reply is very clear in its intent and delivery, as is its gestures, the tied off rope at the end representing a thumb or an outstretched palm when need be.

The delivery of the rope is equally clear when it smacks the pup over the head with its “hand”, rendering him dazed with some floaty, awkwardly timed but amusing distorted eye visuals as the rope snakes away.

Additionally, the angry, pigeon toed walk of the dog suffers from feeling much too stiff and too closed off by the composition of the screen. While the close cut was to accentuate the pooch’s visuals and stress the hit from the rope, the impact reading as more jarring and sharp with the aid of an abrupt cut, it provides little walking room for the pooch to move. As such, his pigeon toed walk feels a little too stiff on accident, not on purpose.

Nevertheless, the camera dissolves back to the Boxer pup from earlier, wrestling and whining frantically with the lobster still clamped onto his nose. The frantic, erratic nature of the dog is conveyed purely through sound effects more than the animation itself—the stakes feel comparatively low with the same, hyper cycle shot on ones to make it feel more alarming. The dog doesn’t even move his mouth to match the whining sound effects.

However, as is usually the case, the intent of the gag is at least clear—a lobster is hooked onto the dog’s nose and causing him pain. After a few more spastic shakes, the boxer is able to free the lobster from his proboscis, said lobster flying through the air and landing in a nearby pottery vase.

Slightly throbbing nose and all, the Boxer cautions a glance over to the vase to view the outcome.

Said outcome arrives in the form of a rabbit. Bugs’ spiral flourish as he arrives out of the vase is worth noting—it would soon become his trademark. A Wild Hare introduces the non-prototype by having him perform the very same twirl out of his hole in the ground. Furthermore, it calls back to Chuck’s tenure in Bob Clampett’s unit, particularly his work on the short Get Rich Quick Porky. Jones was largely in charge with a number of scenes involving a gopher heckling a Plutoesque dog, with said gopher performing the very same twirls and flourishes seen here. Old habits die hard, especially when borrowed by other hands and refined to bigger and better lengths.

On the topic of flourishes, Bugs’ movements are full of them as he entices the Boxer with more magic. His silent, graceful self is a complete contrast to the Bugs in Porky’s Hare Hunt, who was obnoxious and the furthest definition away from graceful that one can find.

Bugs displays the trick up his invisible sleeves in the form of a toy gun, which he wastes no time shooting in the Boxer’s face. While the build-up for the reveal is a little lengthy in all, the contrast between the gentle, slow hand gestures and quick, literal pop of the gun is strong. The only injury the dog withstands is the wobbling of his nose from the impact.

The Boxer’s confrontation is soon interrupted by a bush erupting from the depths of the vase, flowers budding in an instant. With the suddenness of the flowers blooming, instantaneously layered onto the cel of the bush with no animation of them emerging from the leaves—as well as the action being accompanied by a tinkling chime score in the background—provides a comparatively snappier change of pace, a caricature of action whose suddenness cues the audience in that the flowers are of unnatural origin. It’s Bugs’ magic, not the willful act of a bush blooming.

However, the Boxer doesn’t know that, and is met with a streamer in the face from one of the flowers. Signature trombone gobble sound effects provide padding for the relatively unamusing gag.

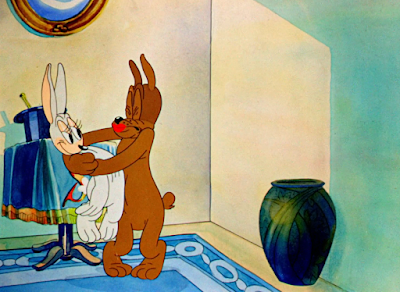

What isn’t unamusing, however, is the transformation between bush to rabbit. While relatively slow and unimaginative in its delivery, the thought is what counts the most, and having Bugs be the bush rather than the force controlling or holding up said bush is much more creative and amusing. The transformation between bush to bunny, regardless of how straightforward it is, flows quite well, especially considering said bunny/bush hybrid is getting jostled around by an angry Boxer pup.

And so, in the midst of the grapple turned embrace, history is made with the first Bugs Bunny kiss of death. Said kisses are relatively synonymous to the legacy of these cartoons, especially when in the hands of Bugs—a surefire, physical manifestation and imprint of one’s heckling. The disgustingly coy eyelash batting thankfully adds rather than detracts or distracts.

However, the Boxer pup is not pleased, wiping the physical manifestation of a physical manifestation off of his lips. The logic of where Bugs’ lipstick comes from isn’t as important as the symbolism behind it—a true representation of the rabbit’s superiority.

Though the growling animation of the pooch suffers from being a little too wooden, the rigidity provides a comic effect, as if he’s so enraged that he can’t even get himself to move. The growl he emanates sounds more akin to a hungry dinosaur than a dog.

End of the show. Bugs’ grand exit is provided not by running offscreen or diving into the vase, but by squeezing himself out of existence as a whole. The general silhouette and framing through negative space is particularly strong and keen to the success of the gag—Bugs truly does appear as though he’s physically boxed within a limit, silhouette hardly braking the shape unconsciously drawn by the viewer’s eye. Staggering the animation and Treg Brown’s “VVVWWWEEOP!” sound effects aid in the believability of the movements, the struggle providing a physical sensation of tension and weight.

While the Boxer pup looks on in bewilderment, the camera dissolves to a more active scene: the littlest puppy and his rope. Here, the pup stalks his prey, mimicking the bloated, slithering motion of the rope on the floor. While the animation is oddly spaced, its evenness causing it to glide a little too much for the desired effect, Stalling’s music score accompanies the action well, speeding up when the pup speeds up, and the flat horizontal staging is simple yet clear. No fancy tricks are needed to view the mimicry. Here, the simplicity works to the gag’s favor.

Pan left to the magician’s next abandoned box of tricks, a chest labeled SHAM-FU AND HIS MAGIC WAND.

Instead of focusing on the contents within, the focus is delegated to one pooch and one rope, both stalking the other cautiously from either end of the chest.

Speed lines are added to the puppy to make his departure feel faster, which fails when the animation itself moves so slowly—the brush strokes only clutter up the action more than necessary.

While the second confrontation isn’t exactly a gut buster either, both surprised takes reversed from their previous stances, the mirror setup of the scene is clear, reflected not only in the staging and timing but Carl Stalling’s music score, where the brazen chords of realization repeat twice. While the gag isn’t particularly hilarious, the symmetrical structure of the sequence makes it more engaging, drawing the audience in by establishing patterns.

Comedy comes in threes, which is why the third attempt between the pup and rope stalking each other is different, having the pup lose sight of his target, who stalks him from above.

Luckily, the rope is able to direct the attention of the littlest pup with a simple flick of a wand. Judging by the smears on the wand and snappy flicks from the rope, the animation may be the work of Ken Harris. A vase is summoned in the air, which drops on the pup’s head with much more urgency than Rod Scribner’s own vase dropping scene with Bugs.

To snap the puppy out of his daze, the rope summons a pitcher of water and gregariously dumps it on top of the dog. Rather than also crashing down on the dog, the vase remains suspended as the pooch dries himself off…

…and then plummets to the ground, lodging itself on the pooch’s head.

Cue yet another “character gets stuck in something” sequence, slowly becoming a trademark in the early Jones efforts. Thankfully, Carl Stalling’s snappy music score of “Black Coffee” adds a much needed burst of energy to the sequence, as opposed to yet another molasses slow scene of a character calculating how to get unstuck. The frantic dog whining sounds have a tendency to become misaligned from the action (particularly during a beat where the dog “stares” at the audience after having tumbled upside down, struggling to get the pot off—that brief, slower beat still maintains the same frenzied whining sound effects that worked best with the equally frantic action.)

After more struggling, the pup is finally able to free himself from the pot, struggling to run out of the way as it falls back down to the ground. He sniffs the shards…

Which are turned into a flock of yellow canaries by the aid of the rope and its wand. The canary animation flows well and is graceful, albeit slow. They possess the same exact weight and momentum possessed by the balloons summoned by the rope shortly after.

Puppy bites into balloon, balloon pops, puppy attacks magic wand. In a rather anticlimactic bout of tug-o-war, the puppy ends up swallowing the wand, though the delivery is muddled and difficult to grasp. A “gulp” sound effect likely would have provided aid where animation could not, but the only clue that the wand has been ingested is the lack of said wand and burst of canaries summoned by the puppy’s hiccups.

Following the rule of threes, an egg is coughed up upon the third hiccup, cracking on the floor. The puppy briefly expresses embarrassment for the mess he caused.

As we dissolve on the puppy now hiccupping a swarm of balloons, focus is shifted back on the Boxer puppy. Much like Dog Gone Modern, the cartoon is comprised of two focal points: what’s happening to the puppy, and what’s happening to the Boxer. Stalling’s score of “The Umbrella Man” resumes, inferring that more rabbit-induced antics lie ahead.

And indeed they do. In yet another creative transition, Bugs makes his appearance through the vessel of a cream pot. The Boxer observes stupefied as the pot bursts into mid-air, pouring its milky contents into the shape of one heckler bunny.

Albeit brief, the Boxer’s small eye take, scored by a quick little chord from Stalling in the music, is a very nice touch.

Bugs’ next act arrives in the form of a cape. He briefly displays that there are no tricks up his sleeves (as far as the eye can see) before draping himself with the cloth. To give credit where credits is due, Bugs’ posing has been particularly strong throughout the short. Careful consideration is paid to his silhouette more than usual, whether it be compressing himself into a square or using his physique to make a conical shape when the cape is draped over him.

Cue another eye take from the Boxer, bigger and stronger in ferocity this time when Bugs reveals himself to be completely absent, save for two glove shaped hands. When Bugs disappears, his hands remain, but now in the form of gloves, complete with glove lines and the empty insides—likely more appealing, easier, and less concerting to draw than regular disembodied hands.

Now, said glove hands stuff the red cape into oblivion. Boxer puppy reacts with another “iunno” head shake. While certain deliveries and executions can falter (such as the ambiguity of the pup swallowing the magic wand), Jones’ pantomime cartoons are largely successful in conveying the emotions of the characters. As mentioned previously, Prest-O is already a step above Dog Gone Modern.

A new cape is unearthed from the security of the Boxer’s ear, black this time. Another eye take from the dog serves as a vehicle to push the gag forward, the grand reveal being a design of Bugs sitting contentedly in an armchair on the other side.

Or so we are led to believe. Sticking to his roots, with Ben Hardaway outright saying that he’d put “that duck in a rabbit suit”, Bugs displays more of the screwball tendencies engrained in his DNA as he honks the nose of the Boxer and clicks his heels, both common attributes of the 1939 Daffy at the time.

However, rather than exiting the scene in a whooping, cavorting mess, the opposite occurs to a degree of slight confusion, with Bugs practically gliding on air as he makes an exit. The glacial timing seems to be deliberate, reflected in the musical accents when he makes contact with the ground, but the delivery comes off as a little too unconfident and renders it as something that seems accidental rather than purposeful.

Such is furthered when the Boxer pup pursues him, darting up the door where Bugs locked himself behind with thrice as much speed and urgency.

Unsuccessful attempts to jar the door open are met with reality bending from the rabbit, appearing from a panel in the door as though it were a drawer and smacking the pup in the face.

Ditto for the bottom “drawer”, Bugs’ tickling the Boxer’s stomach prompting hysterical, decidedly manly laughter from Mel Blanc.

When the ecstasy of that too has died down, Bugs then summons his victim with another “Pssst!”, prompting the Boxer to jerk his head up and hit himself on the drawer, flopping to the ground.

Another smack in the head for good measure prompts Bugs to regress back into himself with another hayseed chorus of “A-hurr-hurr-hurr-hurr-hurr!” laughs. Scenes such as these make it all the more clear why people like Tex Avery were itching to take the rabbit in a newer, much funnier and more charming direction.

Another dissolve back to the littlest pup, still fighting with a bout of balloon hiccups. Rather than reverting back to the previous score of “Black Coffee”, Stalling ties both scenes together with a furtive minor key rendition of “The Umbrella Man”. Fed up with his hiccupping, the pup scrambles to seal his mouth shut.

Another hiccup prompts a balloon to spawn from the inside. A rectangular balloon is the obvious, more funny choice, a much stronger contrast to the little pup’s physique than a regular sphere shaped balloon.

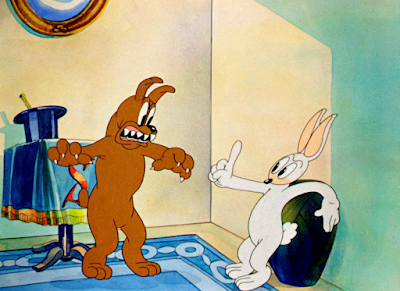

Continuing to bridge the two scenes together, Jones jump cuts back to Bugs and the Boxer. While the cut seems abrupt at first, the persisting minor key score of “The Umbrella Man” again clues the audience in that there is a connection present, hinting that both plots are about to converge into one. Here, Bugs plants another lipstick heavy kiss on the Boxer, prompting him to slam against the door.

Another jump cut back to the littlest puppy continues to bring the two stories together. Indeed, frantic hiccupping prompts the pooch to zoom around in the air as the balloon deflated from inside him, a brief glimpse of perspective animation delivered as he skims past the foreground.

Jump back to the Boxer and Bugs, with some nice symmetrical staging as both sides of the aisle are staged clearly: the Boxer’s rage and Bugs’ indifference.

Another quick cut back to the pup deflating through the house indicates that danger is imminent, especially when the camera makes another cut to Bugs mindlessly clapping his hands together after a job well done. The permanent smile and wide, vacant stare reads as more disconcerting than it does anything else, but his smugness, no matter how mindless it may be, is succinctly conveyed.

SMACK! The plot convergence is delivered in a very anticlimactic collision between pup and rabbit. Again, sound effects carry the impact more than the actual action, which is executed at a laughably leisurely pace.

In any case, the impact is enough for Bugs and the puppy to mow down the door, causing the Boxer pup to get trampled. A brief pause as the Boxer lays limp, offscreen crashes and thuds connecting the dots. While it’s true that an impact can often seen as more violent and subsequently violent when occurring offscreen—Friz Freleng in particular was a big proponent of this theory—here it works as a saving grace, as the action likely would have been too slow or evenly spaced to garner any true reaction if it unfolded onscreen. Jones’ cartoons at this time look fine, with amiable designs and bursts of nice animation, but the mechanics of the movement is what suffered the most.

A camera pan left reveals one dazed puppy and one tied up rabbit. The music score of “The Umbrella Man” returns to a jovial, playful flute chorus as the Boxer uses Bugs’ incapacity as a means to dispose of him. He stuffs him in a small box…

…and stuffs said smaller box in a big chest…

…and stuffs said big chest into an even bigger crate. Innocuous as the gag may seem now, the crescendo in size is reflected in Stalling’s music score, transforming from flutes with the rope to trumpets with the small box to bassoons with the big chest, to an entire brass section with the largest crate of all. The accompanying sizes and weights of each vessel are also conveyed in the Boxer, whose struggle to carry the boxes grows more apparent the heavier they get.

A lock of the crate signifies the end of the rabbit. Littlest pup tinkers over to check out his friend, who’s winded from the entire experience.

Even then, the plot convergence cleverly treks forth, knowing an iris out here would be too unsatisfactory. The littlest pup hiccups yet another balloon, which rises and floats up towards the Boxer. He investigates…

POP! Rather than having Bugs transform from a balloon to a bunny, the balloon explodes onscreen to Bugs floating in the air on the same held pose. A lack of antics or any sort of movement once again furthers the abruptness of the arrival and works to the strength of the scene.

Especially when Bugs pops another toy gun in the face of the Boxer with little anticipation.

The exit of the rabbit, once again granted in the form of shrinking himself down in mid-air, does suffer compared to the first exit. Though the hands remain suspended in the air to clue the audience in that something is about to happen, the reaction time of the dog—while amusing, his growling glower at the audience another early Jonesism of the audience-directed reaction beats—is too slow and allows the hands to remain in place for too long, essentially spoiling the gag.

Regardless, the inevitable is delivered as the Boxer pries the disembodied hands open, Velcro ripping sound effects asynchronous with the action at hand. For once, Bugs’ purely vacant expression indicates that he has the lower hand. Even though he’s a shell of his future self here, future Bugs Jonesisms weasel their way in; when Bugs is in control of the situation, Jones made a point to assert it. The same applies here—the absence of his mindless grin indicates that his plans have gone awry.

And indeed they have. The Boxer retaliates in the best way he knows how—a punch in the gut. Bugs is sent rocketing offscreen.

Additionally, the Boxer’s quick blinks reek of phony sympathy, a great touch that is again purely Jones. Once again, any and all impact from the blow is conveyed purely by the sounds of deafening crashes and mayhem offscreen.

A final camera pan right unveils the reveal: Bugs finally has what’s coming to him, sitting dazed in a fishbowl with a blue black eye. The lamp shade on his head and lone goldfish swimming around in the bowl add insult to literal injury. A rare occurrence in a cartoon directed by Charles M. Jones, Bugs ends with the lower hand.

Proto-Bugs will always remain proto-Bugs. That is, there is no way to make him charming, charismatic, relatable, funny, or likable without a complete overhaul of his character. He’s obnoxious by design, some of it on purpose, much of it not. Not understanding Tex Avery’s nuances and what made Daffy such a hit, pouring all of those surface level inferences into once character is bound to get poor results. Such is the fate of Porky’s Hare Hunt.

While proto-Bugs is still proto-Bugs and will always be proto-Bugs, Prest-O is a considerable step up from Hare Hunt. For one thing, the lack of dialogue (aside from the obnoxious cornball laughter) helps immensely. The Bugs in Hare Hunt talked too much, too arbitrarily, and the things he said weren’t worth all the extra gab—as is often the case with Hardaway’s cartoons. Bugs is still a bit annoying here, mainly the laugh, but the absence of arbitrary dialogue is a major help.

Even then, Jones’ Bugs still seems significantly more polished than Hardaway’s bugs. The taller, skinnier appearance makes him seem more “refined”, for lack of a much better word, more anthropomorphic and less like a feral, nutty, squat rabbit. His movements when performing the magic tricks are much more graceful and intricate than anything executed in Hare Hunt.

Prest-O still has its fair share of shortcomings, but is a much bigger improvement than Dog Gone Modern. While the gags by today’s standards are pretty pedestrian, lessened by glacial timing in both story pacing and animation timing, they’re politely amusing and rescued by appealing drawings and reactions, especially on the part of the Boxer. Stalling’s music scores are a large help as well, motifs and instrument changes illustrating the action and filling in any missing gaps.

Jones’ The Case of the Missing Hare, which has the real Bugs disrupting a magician’s act on stage, blows everything here out of the water, but that’s an obvious given. Even then, it’s fascinating to observe traits and motifs present in the prototype bunny rebirthed and appropriated by the real thing to much more competent and funnier lengths. While Prest-O isn’t particularly thrilling, it’s still a relatively important piece of cartoon history by association, and is much easier to sit through than Porky’s Hare Hunt.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment