Release Date: March 11th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Rollin Hamilton

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Gil Warren (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Man, Elmer, Bill, Monkey, Stool Pigeon, Elephant, Panther, Wild Cat), Danny Webb (Owl, Parrot, Jail-Bird, Panther, Man)

First established with The Isle of Pingo Pongo, Avery hops back to what would soon become ol’ reliable: the spot-gag cartoon.

Spot-gag cartoons served their purpose well. 7 minutes of gags and not much else, they were the type of domestic fodder that could amuse and occupy theatergoers without having to take many risks. When Avery suffered from burnout (which was quite often the case), these travelogues made for a good, mindless buffer, slowly turning into a crutch for the next year or two.

Animator Rollin “Ham” Hamilton also receives his first animation credit since 1935’s Hollywood Capers. Ham was a key player in the early days of the Warner cartoons, examples of his work including the horse’s drunken breakdown in 1931’s Lady, Play Your Mandolin! Hamilton was also a key player at the early days of Disney, heading back in 1935, then reconnecting with Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising over at MGM from 1936-1938 before heading back to Warners for a brief tenure.

In any case, our topic d’jour is the zoo, where various animal exhibits (and the puns therein) are examined.

One of the most gracious aspects of the cartoon is the brisk pace in which it moves. Immediately, Tex Avery wastes no time fiddling with any sort of set up or opening barrage of gags. Narrator Gil Warren greets the audience with “Here we are at one of the country’s most interesting zoos”, met with an establishing shot of the entrance. The play on Kalamazoo Zoo/Kalamazoo promptly tips the audience into the type of humor brandished by the cartoon.

With a triumphant orchestral fanfare in the background, the camera slowly chugs its way over to a feeding time sign on the wall outside the gate. A pause…

…and truck-out to reveal. The blue plate lunch refers to the blue plate special, an affordable meal offered at diners that would change daily.

With that out of the way, we fade in and out to our first exhibit: “The wolf in his natural setting.” Here, the canine sits disgruntled outside of a locked door to nowhere, a pun on the phrase “wolf at your door”.

“Next, a pack of camels.” Referring of course to the cigarette brand, the camels happily chuff their carcinogens, accompanied by a brief music score of “The Campbells are Coming”.

Pan over to our North American Greyhound, a Greyhound bus riding in clunky perspective to a jaunty musical accompaniment of “California, Here I Come”. The animation is a bit mechanical and clunky, particularly on the turns, but the gag is very much clear.

Indeed, such is the genius of Tex Avery. He doesn’t linger very long on each joke, swiftly segueing from one to the next. Therefore, the corny puns are padded by the quick pace—there are certainly no self congratulatory pauses. What you see is what you get, and Avery was very much aware of that.

The next pun of two bucks and five (s)cents is made easier to stomach by the musical accompaniment of “We’re in the Money” in the background. Stalling’s situational music scores absolutely add a lot to these spot-gag cartoons; had it been another composer, they very well could have floundered. The music choices serve as jokes themselves, even if they are equally as corny as their animated kin.

“And here, two friendly Elks.” Said Elks are members of the Elks Club established in 1868 as, initially and regrettably, a social club for minstrel performers. By 1939 it had evolved into a charitable organization and viewed as a fraternity, which is reflected in the gag here of two men greeting each other repeatedly with “Hell-o, Bill!”

Cross-fade in and out to the monkey cage. In a classic Avery role reversal, the monkeys toss peanuts to the spectators, who catch them in their mouths.

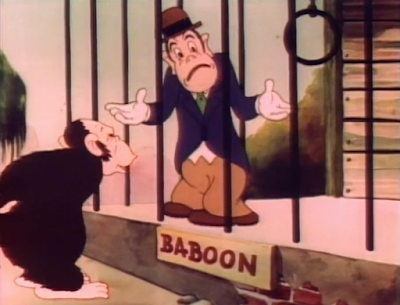

We then segue to the baboon cage, where said baboon admires his human doppelgänger. Some nice timing on the pregnant pause as both human and baboon study their counterparts.

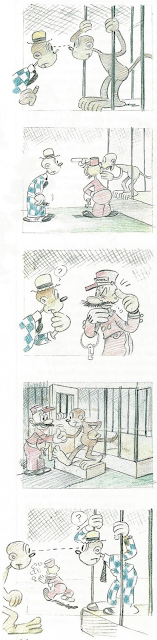

Stalling’s flighty music score of “Mutiny in the Nursery” melts to a subdued yet appropriate accompaniment of “Confidentially” as the baboon calls the zoo keeper over and whispers something into his ear. Said zoo keeper is rife with Avery’s design sensibilities, from the bulbous nose to round eyes. He could pass for a relative of proto-Fudd’s.

A dissolve to the payoff makes the joke land harder thanks to the abruptness—showing the zoo-keeper throw the baboon out and the guy inside would ruin the surprise and slow down the momentum. Again, props must be made for Avery and his knack of timing. He knows how to judge which jokes should get the most or least amount of time.

Unfortunately, storyboards for this particular gag paint a much more egregious and blatantly racist picture. The changes present in the final product are very much welcomed, but knowing the origins of the gag make it much harder to fully appreciate.

In any case, the camera pans to a gag that is genuinely funny and easier to appreciate; confronted with a “DO NOT FEED THE MONKEYS” sign, an elderly woman spares a few furtive glances to see if she’s being watched. Stalling’s moody, apprehensive music score add a welcome bit of ambience and trepidation that likely wouldn’t have had the same effect with a more chipper music score.

Fishing a bag of peanuts out from her purse is infinitely more funny than having the peanuts in plain sight. And, rather than feeding the monkey one by one, she just hands him the entire bag, grinning as though she’s just done a terrific favor.

All of those subtle aspects combine for a classic, perhaps even predictable but all the more enjoyable payoff as the primate socks the back of peanuts right back in her face, screaming “HEY SISTER! CAN’T YA READ?????”

The echo left from Blanc recording on an open stage always does wonders with his signature scream, allowing it to hang in the air just a few milliseconds longer.

A confrontational music blare as we fade out makes it seem as though the “sister” has just committed a felony. It’s worth nothing that Avery would reprise the same gag in his Circus Today, where it’s revealed the act of feeding monkeys IS actually a felony.

With that, the mood transitions back to a more chipper scene as the narrator introduces us to the “nature’s own weatherman”…

“…and his shadow.”

“Over here, we find—“

Boisterous off-screen chuckles interrupt the narrator. The camera pan slows down, growing uncertain, as though the audience is viewing the cartoon from the eyes of the narrator; a very clever touch to ground and immerse the viewer.

Soon, the camera pans to the culprit of the chuckles; a proto-Fudd doing what he does best, being an obnoxious pest interrupting the flow of the cartoon. Here, he blatantly disregards the “DO NOT TEASE THE LION — DANGEROUS” sign, poking a stick throw the cage and erupting into shrieky hysterics of laughter. His Joe Penneresque personality is all but absent now, with Blanc fully taking the reigns of the character.

Narrator chastises Elmer in that typical, patronizing 1930s narrator cadence. In fact, his line of “Shame, shame. You’re a bad boy!” is meant to be as deliberately condescending as possible. Even better is the fact that it works—Elmer sulks off-screen and takes on the persona of a guilty 5 year old, rather than a fully grown adult who is a complete nut job.

Back to the puns, the narrator purposefully highlighting his wordplay on “The skunk age is always a scenter of interest,” with a self congratulatory pause. The framing of the wide shot certainly works well in conjunction with the purposefully corny wordplay.

Truck and dissolve into the skunk cage, where the reveal is granted in the form of a self help book. Avery had briefly dabbled in the “unlovable skunk” territory before with 1936’s Don’t Look Now, and would later make an entire cartoon dedicated to the cause with his Little ‘Tinker over at MGM.

Next order of business is feeding time for the giraffes. Here, the zoo-keeper literally shovels food into the mouth of the giraffe, perched atop a ladder.

Treg Brown’s sound effects and the layout of the sequence are the true winners of the gag—the food sounds like 10 tons of aluminum crashing together as it slithers down the giraffe’s elongated neck, the camera following dutifully.

Cue a tremendous crash as the food hits the giraffe’s hut and sends it crashing to the ground.

Norm McCabe would take a more whimsical but straightforward and similar spin on the gag in his Who’s Who in the Zoo, very similar in nature to this one (as most spot-gag cartoons are.)

Back to Elmer, still hyucking it up as he teases the same lion with no remorse. Elmer’s constant state of mindlessness in the Avery cartoons works to its advantage—he shows no remorse and is the perfect vessel for Avery’s desire of interrupting the flow of the cartoon. He takes on a Droopyesque quality in that he can pop up at any minute at any turn, a more spritely, omnipresent force rather than just some oddball.

The little jump o’ guiltiness he does when he’s been caught, hiding the stick behind his back inconspicuously, is priceless, as is the childish swaying back and forth.

Enter the first usage of a radio catchphrase that would soon frequent many a cartoon. Here, Elmer recites the nasally wisdom of one Lou Costello: “I’m a baaaaad boy.”

Our next gag of rabbits multiplying would be beaten to death by both more spot-gag and Bugs Bunny cartoons alike. The novelty of it making its first appearance here is certainly worth noting.

“Now, over here in the birdhouse, we find the wise old owl.” Transitioning to a bunch of birds flitting around in the birdhouse, paired with a score of “Bob White (Whatcha Gonna Swing Tonight?)” harken back memories of Tex’s first and most formative spot-gag cartoon, The Isle of Pingo Pongo.

Voiced by Danny Webb, the owl recites some back and forth dialogue previously heard in Chuck Jones’ The Night Watchman. Not that Chuck Jones was someone who couldn’t have any material to borrow, but it certainly is strange to see Avery borrow from Jones and not the other way around, which was typically the case with all of the directors.

“Who?”

“You.”

“Meeeeee?” Webb’s bewildered, shrill voice crack is hilarious.

“Yes.” Warren’s deliveries are an unwavering deadpan.

“Ooooohhhh.”

Mimicking the guilty confrontation of Tommy Cat in Watchman, the owl is quick to shy out of view, which Avery uses as an excuse to pan over to our next center of interest: the South African talking parrot.

Narrator wastes no time patronizing the bird with “Polly want a cracker?”

No response.

Frazzled by the lack of an answer, the narrator clears his throat, repeating himself louder this time. Norm McCabe would again borrow this gag in 1941’s Robinson Crusoe, Jr.

“Nahhhh.” Parrot’s voice is grating and deep. “Gimme a short beer!”

A razzing music score and aloof stance leaning against the birdcage strongly assert the parrot’s personality and dominance. Even the animals are sick of the narrator’s condescension—a rather reoccurring theme in the spot-gag cartoons.

Avery’s next gag serves as a precursor to one of his best cartoons at Warner Bros. and his next cartoon after this one, Thugs with Dirty Mugs. Here, the “Alcatraz Jail-Bird” speaks à la Edward G. Robinson, peppering his “I didn’t do it” speech with plenty of “see”s and “yeah”s. Robinson would be a common topic of parody in these cartoons for years to come, perhaps one of the best being Friz Freleng’s Racketeer Rabbit.

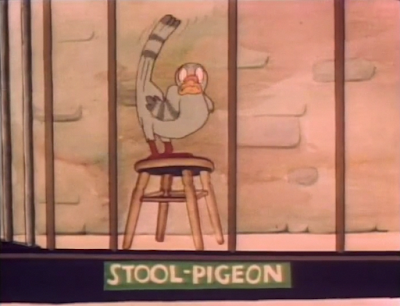

The conjoining stool-pigeon pun, another joke frequented many a time by many a Hollywood cartoon, is elevated by Blanc’s effeminate deliveries of “Oh, he did so do it. I saw him with my very own eyes.”

A “so there” asserts the pigeon’s smug finality, as does a pompous flick of the tail.

When confronted with a mother ostrich, the only fitting musical accompaniment is, of course, a flighty score of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby.”

In the midst of showing off her egg, the ostrich trips over a stray bucket, causing her to stumble and lose the egg. Her pompous walk carrying her child-to-be is especially nice, paired with Warren’s patronizing but fond comments. The egg falls to the ground…

“Well! A jackpot!”

Balancing out the serenity of the previous scene, Elmer returns with Blanc’s contagiously hysterical giggles and “Cootchie cootchie coo!”s. The animation itself strikes a great balance between the ginger taunts of Elmer and the snappy, heated head butting from the lion. Movement from both the lion and Elmer are equally fast and equally frenetic. Elmer’s line of “THIS IS SUCH FUN!” neatly and gleefully tie the scene together.

Of course, he receives yet another scolding from the narrator, prompting him to hide behind a tree. The repetition of “I’m a bad boy” is overkill, but the overall character acting make it a little more excusable.

Cue another gag borrowed in a few cartoons, one of them being Bob Clampett’s Africa Squeaks. Here, “Joe Jumbo” talks on the phone in a nasally drawl. His “Hewwo? Expwess company?” predates the ever iconic Fuddspeak that would only take a few more months to debut in these cartoons. Arthur Q Bryan had performed the voice before ever joining the WB crew or voicing Elmer, and his first role as the eponymous Dangerous Dan McFoo a few months later would be a turning point in voice acting history.

Nevertheless, the inevitable reveal. “You know, those guys have had my twunk for a week…” A bloated pause allows the audience to get the joke if they hadn’t already.

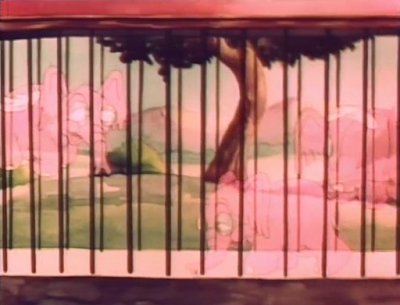

On the topic of elephants, the camera pans over to leftovers from “that last New Year’s party”. Pink elephants, for those unaware, are synonymous with intoxication, first deriving from the 1913 novel John Barleycorn, mentioning how one of the "two types of drinkers" is the man who sees pink elephants in the midst of his alcoholic delusions. Though most people have come to (rightfully) associate the phrase with Disney’s Dumbo in 1941, Friz Freleng’s 1940 Calling Dr. Porky is a cartoon dedicated to a man frantically trying to outrun his own case of mischievous pink elephants.

Next order of business is a pair of panthers pacing in their cage. Separated by a pole, the panthers exchange countless “bread and butter”s, a superstitious phrase said when two people are split by any sort of barrier.

Our narrator then introduces us to one J. Wellington Buttonhook, his face concealed by the newspaper he’s reading. “Mr. Buttonhook used to thrill thousands at the circus by putting his head in a lion’s mouth.”

Stalling’s score of “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” crescendos to accompany the inevitable payoff. As is the case with most—if not all—of these gags, the deadpan execution and swift transition to the next piece of action serves the gag favors.

Interestingly, the next scene is quite the opposite of deadpan. In fact, it taps into the trends of Avery’s earlier cartoons that he has since outgrown. We’re met with the rocky mountain wild cat, who screams and garbles and hops in hysterics, cartwheeling and jumping all over his cage not unlike a certain crazy, darn fool duck. Had this short been released two years earlier, Bob Clampett would undeniably have been tasked with animating this scene.

The cat’s vacant, cross-eyed stare when confronted by the narrator is priceless. “Just what made you so wild?”

“What made me wild?” The cat may very well be one of Blanc’s best performances of the cartoon, tied with the gleeful hysterics eliminated from Elmer. “What made me wild!?”

The camera pans closer to the wild cat, matching the intensity growing in Blanc’s voice. “They called my name out at Bank Night…”

“AND I WASN’T THERE!!! RRRAAAAHHHHHHHH!!!”

Cue more hysterics. Bank Night was an event held by theaters during the Depression where audiences would enter their names into a raffle, winning prizes if their names were called. Prizes could often entail cash, which, during the Depression, was more sacred than ever.

At last, we visit the victim of Elmer’s taunts once again. Following the rule of threes, the lion gets taunted thrice, the fourth time showing a much more leisurely scene. Satisfied, the narrator prattled on about the “little fella” finally taking his advice and going home.

Lion wakes up to contentedly shake his head, happily pointing to his mouth.

Shaky truck-in to the opened mouth, where two eyes appear from the darkness. A third “I’m a bad boy” is monotonous at this point, but the echo and total lack of a music score makes for a comedically chilling scene.

Iris out on a well-fed lion.

For a spot-gag cartoon, A Day at the Zoo has a lot of potential to fare worse than it does, and is personally one of the travelogues I enjoy more. It drags in comparison to The Isle of Pingo Pongo, which, for all of its flaws (ie racism), fared better as a snappier and more visually appealing cartoon.

However, Zoo doesn’t try to be something it’s not, which is the most admirable portion of the entire cartoon. It’s a 7 minute string of gags and presents itself as a 7 minute string of gags. There’s no attempt at an overarching story. The gags move swiftly from one to the other, and what you see is what you get.

In any case, it’s a hard cartoon to hate. Blanc’s deliveries as Elmer are contagious, and I’m partial to Danny Webb’s incredulous lines from the owl myself. Most of the jokes are harmless fun, or have thankfully been tweaked to be more harmless (re. the baboon gag.) It’s not a legendary piece of filmmaking by any means, and sadly, quite a few of Avery’s spot-gag shorts would only worsen in quality from here, but for a 7 minute string of gags, it adequately serves its purpose.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment