Release Date: August 24th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Norm McCabe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Elevator Operator, Bugs, Owl), Ben Frommer (Dr. Chris Chun), [presumably] Mary Shipp (Receptionist), The Rhythmettes (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Seeking to recreate a previous bout of success is a natural impulse. If something is met with warm reception, then who wouldn’t want to chase and harness that high? Study what makes it so successful, what constitutes success to begin with, seek to apply said methods to one’s current mission of choice. Artists in particular are sensitive to identifying what makes a piece successful, what success means to them, and so on. That goes doubly for the directors and cartoonists of Termite Terrace, whose careers were dependent on making films that were receptive to both audiences and themselves. If an audience continually expressed distaste at a director’s series of cartoons, said director was treading water.

Therefore, Bob Clampett seeks to recapture the highs of The Daffy Doc with a new reprise—Patient Porky. That Doc was the film of choice potentially indicates how audiences received the short at the time; that is, well. A 1938 entry in The Film Daily, a trade publication, bestows the honorable title of “Funny Short” in a brief review of the cartoon, expressing particular interest in “a hilarious sequence winding up the short.” Said hilarious sequence is replicated in Patient Porky.There is a reason why fans praise The Daffy Doc and not Patient Porky. A sanitized copy of the former film, Patient places a priority on hospital related gags and happenings, with a crazy cat posing as a doctor stepping up to make Porky’s life miserable instead of Daffy.

To best encapsulate the reputation of Patient Porky, one finds themselves turning their attention to the title card. Whereas Doc’s title card featured an animated loop of two ducks roaring through town on the back of an ambulance, Patient merely takes a snapshot of the same scene, dousing the subjects in a vague silhouette; not even the benefit of a background is received. Likewise, the anticipatory, jovial, and invigorating music strains are shelved in place of a melodramatic dirge. Doc’s introduction rouses the audience through an exhilarating playfulness—Patient’s introduction encourages the audience to think of pleasantries such as funerals and suffering. The most apt summation of the cartoon, both as itself and compared to its predecessor, can be gathered just by analyzing the title card.

Boasting a runtime barely over 6 minutes—including the time allotted for beginning and end titles—renders this as a short cartoon. That isn’t a problem in itself; sometimes a cartoon of such length prevents the director from burning out and struggling to stuff the plot for an added minute. In spite of this, trademark time fillers ever native to Clampett are still abundant, as evident by a facetious disclaimer hoping to capitalize on the wordplay between The Rains Came/The Pains Came.

And, of course, a signature establishing shot of Clampettian descent: pause on the scenery, ease the camera in, have two objects on a painted overlay part to each side in an attempt to simulate depth.

While the opening is much less climactic than the exhilaration of The Daffy Doc, a suffocating sense of foreboding intended through the music dirge is successfully communicated. Such a dramatic up shot places the viewer directly into the cartoon, experiencing the views vicariously through the camera—likewise, the drastic angle feels much more overwhelming, monolithic. Perspective on the staircase feels comparatively flat, as though looking at the tops of the steps rather than the sides, but doesn’t detract from the tone communicated.

An interior shot of the hospital is, likewise, another throwaway means to fill time. Functionality is comparatively more innate than the previous two shots, as a view of a receptionist talking into the intercom while various nurses and patients stroll the hallways have the benefit of both dialogue and animation. Said animation is certainly on the cruder side (reused from The Daffy Doc), characters appearing to jitter as they walk and talk. An additional camera pan to the elevator suffers from an unbalanced momentum and unbalanced movement, though difficulties with the camera department and their evolution have been well expounded upon.

Despite the show having been on the air since 1932, only recently have the Warner crew embraced the potential of The Jack Benny Program. References to Benny and his show wasn’t a pop culture trend exclusive to the late ‘30s and early ‘40s shorts—the cast of the show would lend their voices to The Mouse That Jack Built, a Bob McKimson effort from 1959 that features a live action cameo from Benny himself at the end. Considering Mel Blanc’s ties with the show, spoofs come at no surprise. If anything, it’s a logical impulse.

Keeping that in mind, a crude—both ethically and artistically—caricature of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson occupies the next 25 seconds of the cartoon. Great for audiences in 1940 who not only were fans of Rochester and Benny’s radio show, but who were also relatively unexposed to Blanc’s many, many impressions of Rochester. Not so great for modern audiences who are either unaware of the character’s shtick or are rightfully put off by the caricature.

Even then, egregiousness aside, perhaps the biggest sin is that his presence is so taxing. Such a deduction stems more from a post-Benny world, which isn’t fair to the cartoon itself, but listening to a character hawk all things alliterative (“First floor! Ague, asthma, anemia, arthritis, aches and apoplexy!” “Second floor! Beriberi, biliousness, bronchitis, bends and blind staggers!” and so on) for half a minute without the benefit of any sort of visual interest does get arduous.

Part of that can be contributed to laziness. To indicate that the elevator has gone up a floor, the camera merely jolts inward at a slightly intimate angle, the light on the inside of the elevator indicating that distance has been traveled before the doors open. Same routine repeats for the third time, the camera resetting to its original register on the first floor instead. It is certainly economic, and while there is a certain admiration to be had for discovering such a workaround, the result is painfully lazy and under-stimulating.

Constructing and painting a new layout for such a repetitive action can be burdensome, sure, but that is a risk that must be taken when dedicating a near half minute to the same gag looping thrice. A mere camera pan upward or even just animating background elements in perspective to simulate movement of the elevator, elevator and camera itself remaining planted, could introduce a much needed means of visual interest.

Nevertheless, as a reward for such meticulous, laborious, and stimulating animation, another still shot seeks to take a breather from the dizzying momentum so undoubtedly exuded by this thrill of a cartoon. Facetiousness aside, a glance at a birth chart outside the maternity ward does bear the honor of being one of the first instances in a Warner cartoon to make a joke about rabbits multiplying. Tex Avery has the honor of being the first with A Day at the Zoo.

Enter one of the last instances of a prototypal Bugs Bunny. His inclusion is certainly of interest—he follows Bob Givens’ design for A Wild Hare, but still speaks in a hayseed, toothy accent (albeit in a somewhat lower register than what is touted in his previous appearance) with guffaws a-plenty. And, most curiously, he’s colored to be all white instead of gray.

A Wild Hare just barely released before this, so it was still wrapped up in production while Clampett’s team was tending to this one. Though only a theory, it is possible that Clampett caught wind of the rabbit’s redesign, but only ever saw glimpses of some model sheets. Such would explain the lack of coloring—he is white on the paper, after all—as would the attachment to his prior mannerisms, as it’s unlikely Clampett or Warren Foster would have been privy to the whole story/execution of Hare. Cartoons were written collaboratively in those days before each unit was assigned a writer, other writers or crew members pitching ideas and suggestions but not overseeing the production. So, while he may have known it was being produced, Clampett wouldn’t have known of the nuances to Avery’s newly revised rabbit.

Whatever the case may be, it is certainly curious how Clampett never utilized the screwball rabbit prior to this. Seeing as he had “adopted” Daffy from Avery, it makes sense—he already had a comparatively fleshed out creation at his disposal, and one he knew well considering it was Clampett who provided animation for Daffy’s hysterical exits in Porky’s Duck Hunt. Regardless, his acquisition of the duck certainly didn’t stop Clampett from making a series of shorts with other screwball zanies. The proto-Bugs has only appeared exclusively in the more “prestigious” color Merrie Melody cartoons (Porky’s Hare Hunt notwithstanding), which could be a possible barrier for Clampett’s exclusive contract with the black and white unit.

Bugs’ cameo is brief, only here to offer a proud correction to the statistics.

A wink at the camera is a bit gratuitous, but innocent and perfectly in line with Clampett’s constant embrace of innuendo.

A hurr hurr-ing exit of guffaws is equally gratuitous, but is somewhat earned; if Clampett was the one to first animate Daffy’s whooping exit that would become a trademark of his character, then he has the rights to instill that philosophy on the knock-offs, too. Brevity of the exit maintains swiftness in momentum—a rarity for this cartoon—and makes his fit of hysterics seem stronger. Short, sweet, to the point.

With Clampett cartoons come pop culture references—a recurrence that seems to be more of an indulgence than a desperate scavenge for laughs (though does aid in that department as well.) In this case, Jean Hersholt’s character of Dr. Christian from the 1937-1954 radio show of the same name is penned as Dr. Chris Chun. Flimsiness of the wordplay is noted almost in endearing amusement—Patient Porky is to The Daffy Doc as Dr. Chris Chun is to Dr. Christian.

Polish actor Ben Frommer supplies the heavily accented strain’s of the doctor’s voice. Best known for his roles in movies such as Scarface, IMDb (which is hardly reputable but suffices in a fix) indicates that this cartoon is one of his first acting roles. Curiously enough, Frommer would pop up in a number of Warner films late in the studio’s lifespan—The Last Hungry Cat, I Was a Teenage Thumb, and Transylvania 6-5000 all boast his vocal talents.

The patients of the hospital greet him through the courtesy of a somewhat stilted wide shot, hindered more through crude animation and draftsmanship rather than layout. Keen eyes can catch a “Foster” on the bed closest to the camera, a shout-out to writer Warren Foster himself.

Introduction of the doctor does simulate some semblance of plot, but not much. Really, he’s a vehicle to support various hospital related sight gags and puns, as our first patient indicates:

PATIENT ————— OLLEY OWL

AILMENT ————— LOSS of VOICE

A somewhat clever camera pan reveals the symptom, the maneuver and execution of the camera debatably more funny than the punchline itself:

SYMPTOM ————— HE JUST DON’T GIVE A HOOT

If anything, Stalling’s plucky musical accompaniment of “Start the Day Right” is welcomed. Its flightiness is a welcome change of pace from the droll funeral dirges so concentrated in the beginning.

“And how’s the sore throat this morning?” Composition is clarified and inventive through using the doctor’s head as a frame, the negative space around the little owl naturally guiding the audience’s eye. A similar technique was additionally utilized in Porky’s Picnic.

Owlet complains that he can’t talk above a whisper; evidently, his sentences are laden with truth, as even the doctor asks him to clarify. As he leans closer, the invisible frame in the composition tightens, the owlet a stronger visual priority.

“I said…”

His hysterical outburst of “I CAN’T TALK ABOVE A WHISPER!!!” is one of the highlights of the cartoon—it takes work to ruin a certified Mel Blanc scream. Likewise, the crescendo to such a point enables a more impactful contrast. Softness of the owl’s voice and his general condition allow for the punchline to come as a surprise. At least, a surprise to those unfamiliar with the novelty of Blanc’s piercing yell purposefully cutting through the momentum of a cartoon.

Despite the adjacent sequence not boasting the same comedic superiority, John Carey’s sculpted animation never fails to appease the eyes. Likewise, a slight up angle of a dog asking about his leg places a visual priority on his injury. The sling hoisting his leg makes the elevation feel higher, more tactile. Such meticulous perspective is easily tackled through Carey’s handiwork.

Integration of an X-Ray seeks to take advantage of the hospital settings the best it can; one supposes looking at a literal translation of bones knitting is more novel through the vessel of an X-Ray rather than cross dissolving to the interior of the dog’s leg itself. With that in mind, even Stalling’s somewhat childish, comic music score seeks to acknowledge what a lame sight gag the audience has been presented with.

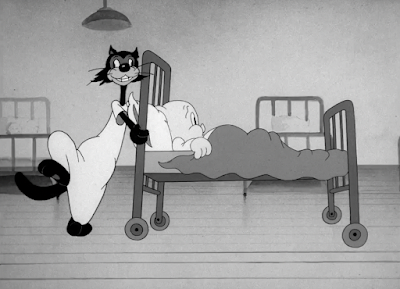

Dissolving to a pair of patients, does, surprisingly, introduce some semblance of a plot. A cat who seems to have no particular ailment serves as Daffy’s successor. Clampett understood screwball characters and handled them with a bit more nuance than, say, the aimless hysterics of a Ben Hardaway screwball, which does come in handy. Keeping that in mind, the cat is a pale imitation of a much more faceted character who—despite his primitiveness at the time of conception for The Daffy Doc—could boast a broader range of emotions other than just “crazy”.

As our analysis for the aforementioned cartoon discusses (which you can find here if the opportunity was missed before), Doc was a bit of a cornerstone film for Daffy in that he is visibly reactive and receptive to the events unfolding around him. Such a privilege was not always available prior. In the short, he feels injustice, he feels anger, he feels contemplation, he feels inspiration, and he certainly feels daffy. While such attributes are crude and rudimentary in comparison to the depth and variation his character would be privy to later on, his service in The Daffy Doc dispels rumors that he is just a vessel for loud noises and hyperactivity with nothing else in between.

As was just mentioned, even the cat isn’t just a means for loud noises and crazy expressions. Clampett understood that wild antics and screwball hysterics especially were best approached through a build up and justification for the breakout. In this case, the cat is cognizant enough to understand he has an audience; his voice points to some suspicions of his being a character as he gurgles a joyful “Watch this!”—fervent, frankly annoying chuckles cement such deductions.

Even then, as he tiptoes over to a patient who evidently swallowed a piano (no such indication reflected in the drawings, savoring and encouraging any curiosity from the viewer), he seems more like a pest than a loon. There is very little to the cat’s personality—he is crazy and the denizens of the hospital are his unwilling subjects—but the repeated switching between deceptive normality and little breaks of daffiness attempt to keep the audience engaged.

A side note, keen eyes will note literal writing on the walls as the cat tiptoes along the room. Camera directions indicating a pan are accidental in their inclusion, but amusing nonetheless; the writing is faint, and theatrical audiences certainly wouldn’t have noticed, but it does remind the viewers of the human hands and minds poured into these cartoons. Such a dose of humanity is welcomed in the otherwise sterile and cold nature of Patient Porky.

More animation courtesy of John Carey eases slow pacing through drawings that are solid, tactile, and visually appealing. Said pacing is justified in its lugubriousness, as it allows the ear shattering glissando of piano keys as the cat aggressively runs a finger on the hippo’s stomach to crack above the muted hum of the music, though the entire sequence does not exactly justify the half minute of runtime it is given.

Brush trail effects on the cat darting back into his haven of a bed maintain the energy of his exit, the strokes still lingering in the air after he’s situated to simulate the impact of his speed sand energy still in the room. Likewise, the discontented, accusatory glances of the hippo are some of the most appealing drawings the short has to offer.

Any viewers hungering for a return of the egregious Rochester caricature and his never-ending alliteration are sure to be appeased at the familiar sight of an elevator approaching a new floor. Thankfully, his presence does constitute the cartoon’s title, as Porky only shows up in his cartoon over halfway through the runtime. As if to stress his miraculous introduction further, the Rochester caricature’s introduction of the floor all start with the letter P.

Whereas Porky’s participation in The Daffy Doc was unwilling, with Daffy having to knock him unconscious and drag him from the street to be his unfortunate subject, he is indeed a willing patient this time around. Complaints of a stomach ache are preceded by a catchphrase recycled lovingly throughout many Warner cartoons, seeking to capitalize on the literality of the setting here: “Is there a duh-dee-dehh-dehh-doctor in the house?”

“A doctor?” A sneaking suspicion indicates the cat is not exactly qualified for the job.

It’s ever convenient that Dr. Chris Chun is out of the room, but the antics with the cat and the hippo (as well as the cross dissolve to the elevator indicating a passage of time) are enough to justify his exit. That, and the film would be without any conflict—something desperately needed to pique the interest of the viewers. The cat asserts his uniqueness—and comparative lack of professionalism—compared to Chris Chun by rushing past the patients with zeal that casts are twisted and patients cling to their beds in the process.

Furthering his enthusiasm, the cat doesn’t reach a complete stop until circling a hapless Porky. Asserting the cat’s daffiness is, oddly enough, comparatively more obtuse than Daffy’s screwiness in The Daffy Doc. It seems contradictory to say given that the aforementioned short introduces Daffy’s role by having him throw sharp instruments in the air and wreak havoc in the operating room, but his quest to actually nab a patient is carrier more through his actual thoughts (or lack thereof) and actions.

Here, the filmmaking seems to spoon feed the idea that the cat is crazy through off kilter, comic music scores, laborious beats dedicated to what a wild and crazy guy he is, dedicating spotlights to the effects of his impulses (such as the aftermath of his running prompting a tailwind through the hospital.) Clampett’s approach to filmmaking is more nuanced and less transparent in Doc, allowing the audience to read between the lines when necessary.

In any case, the cat’s formal introduction hinges yet again on the shoulders of pop culture. “Young Dr. Chilled-air” is a grasp at the fictional Dr. Kildare; originating from a short story in a 1936 issue of Cosmopolitan by Max Brand, the character achieved stardom through books, films, radio, and even a TV series in the ‘60s. There is a fondness in the availability of the cat’s business card, as though he has been waiting years for this moment (or Porky could have just been his third “patient” of the day, introducing the possibility of other tortured souls victim to his antics preceding the time of this cartoon.) Such wordplay, flimsy as it may be, is more effective through a wry closeup painting than it would if the cat merely introduced himself verbally.

Norm McCabe animates a close-up of Porky describing his ailments. He often served as Clampett’s choice for pronounced dialogue scenes, possessing a serviceable nuance and solidity in his work that equips him for the task but doesn’t seem like a waste of ability (such as if John Carey, often best for his tactility and energy, were tasked with a static dialogue scene that didn’t utilize his strengths properly.) Writing continues to alleviate the morose atmosphere of a hospital setting. Instead of giving a flat explanation of his ailing stomach, Porky instead insists “I had a ehh-buh-be-ih-birthday party, an' I guess I ate too ehh-muh-mi-mu-uhhh-muh-mih-ehh—I made a pig of myself.”

While the character animation itself is a bit crude and at times vague, the decision to have the cat being the X-Ray in from the foreground (thusly slamming it against Porky’s body, who is not in the optimal condition to take such abuse) succeeds in introducing necessary depth to the scene. Porky’s pill box hat is taken advantage of in its few appearances here, aimlessly bobbing along his head in a follow through long after he’s stopped moving himself.

On the topic of overzealous motion, a decision to truck into the X-Ray struggles to bridge the impending close-up of the next scene. Instead of providing a seamless and creative transition, the janky movement seems arbitrary and aimless—the camera barely has any time nor room to truck in before the next shot is greeted through a jump cut.

Nevertheless, the reveal of the X-Ray may very well be one of the most inspired pieces from the film. (Then again, such a deduction may be more of a result of projecting rather an objective fact, as it is one of my favorite aspects of the cartoon.) An entire birthday cake perfectly lodged in Porky’s stomach is plenty humorous on its own, humbling his polite claims of “I guess I ate too much.” Yet, the details are what solidify the joke: the candles on the cake that are still lit, the plate swallowed whole, and the few slices missing implying that Porky was at least gracious enough to share.

While the visual itself is great, the implications behind such a visual are what truly cements the endearing absurdity of the outcome. Allowing the audience to read between the lines makes a punchline all the more rewarding, which is where our previous discussion of The Daffy Doc and its success comes to play. An obtuse cartoon such as Patient Porky is rare and fleeting in nuances such as these (if one would call 3/4 of a cake with candles burning in someone’s stomach “nuanced”.)

Caricature of Porky’s heartbeat is likewise successful; a mere shape of a cartoon heart clicks dutifully along on a pendulum, obeying Stalling’s infantile orchestrations of “Here We Go ‘Round the Mulberry Bush.”

Ever the beacon of hospitality and consideration, the cat in the foreground troubles himself enough to blow out the candles on the cake. Having the X-Ray shut off at the same time is an admittedly creative transition that comments upon the coy impossibility of the gag to begin with. No justification desired nor needed. Perhaps the cartoon would be better off if such mischievous, unapologetic ambiguousness was present throughout.

A brief cut of the cat “helping” Porky suffers greatly from stilted, awkward animation, particularly on Porky himself. His proportions are a bit off to begin with; his body is wider than usual, and a part of that is to accommodate the staging the X-Ray so that it aligns with his body. Nevertheless, his shoulders seem rise above his head, making him look hunched and awkward.

That, and his head barely seems attached to his body when he starts to walk. His construction over all is loose, vague, unanchored, appearing more like a paper puppet simulating motion than an intended three dimensional vessel occupying and interacting with a space. Thankfully, it’s only for that one shot—the following scene is still somewhat floaty and lugubrious in its pacing, but the characters possess enough construction to give the illusion that they have depth.

A part of said lethargy in the animation is purposeful. After gurgling vague reassurances such as “Take it easy,” and “Gently,” the cat directly contradicts himself by suplexing Porky into a hospital bed with much more vigor. For viewers watching this cartoon for the first time, the maneuver does come as a genuine surprise. Its execution may not be the most graceful, but is effective in its subversion.

Additionally, Porky changing into a hospital gown is cleverly cheated by having him tumble out of his clothes and into the gown on the bed from the force of the fall. With physics on his side, his jacket and hat obediently hang themselves on a nearby hook. Such preserves the mounting momentum and reduces the need for any additional cuts or dissolves that pad out the time.

A closeup of John Carey’s animation is much appreciated in its firm construction, appealing draftsmanship, and energy that feels genuine rather than manufactured and forced. In a world where screwball characters are trademarked by their crossed eyes, the crazy cat attempts to establish his status as the inverse of The Daffy Doc by possessing a wall-eyed expression of equal insanity. Seeing as it’s such a comparatively sparse interpretation, the change is welcome and novel, though not exactly substantial in it’s substitution.

“Hey gang! I’ll make some tea and we’ll cut the cake!”

Comparisons to the short’s unofficial predecessor become more significant with Porky in the clutches of the cat. Both Daffy and the cat have the same motivation, as revealed through a song number courtesy of The Rhythmettes: both want to perform surgery on an unwilling Porky.

Daffy’s reasoning was somewhat more warranted—insanity is a contributing factor, of course, but he begins in the short as a doctor’s assistant, gets thrown out of the operating room for being a loon, feels his rights have been infringed upon and vows to get a patient of his own in order to prove himself worthy. As mentioned in the corresponding analysis, his line of logic (or, perhaps execution of said logic) is certainly warped, but does make sense. Even if only to him.

Here, the cat’s motivation is more out of left field. We know he’s crazy, we know he’s faking as a doctor, but he doesn’t exactly possess a compelling background to warrant his actions. Any indication of his wanting to be a surgeon is spoon-fed through the lyrics of the song (“I’ve got a terrific urgin’ to be a famous surgeon”.) The audience is intended to accept his claims as fact and be compelled to follow his journey. Patient Porky continues to buckle under it’s irrefutable objectivity, making for a rather flat story and prevailing attitude of disinterest.

Regardless, the song number is another bright spot of the cartoon. I too confess that such a deduction is again based more in opinion than fact, as this is tied with the opening song sequence in Porky’s Romance for my favorite song number in a black and white Looney Tunes short. Harmonies courtesy of The Rhythmettes are difficult to object against, and the lyrics—outfitted to “We’re Working Our Way Through College”—display a lighthearted playfulness the short could benefit from more. (For example: “The patients always show a lot of indecision, but afterwards they brag about their big incision”.)

It certainly isn’t one of the best song numbers in a cartoon by any means. Much of the praise comes from context; whereas song numbers can slow the plot or be a transparent means to fill time, Patient Porky has been such a painfully mediocre outing that the shift in tone and energy is a godsend. It’s something different, a change of pace, and a pace that is jolly and brisk.

Certain staging devices flashes throughout the number benefit in their creativity. An up shit of the operating theater is particularly striking through the dramatic angle, a contentious balance between dark and light values creating a visual hierarchy that is clarified through framing devices such as the patrons in the seats, or even a lampshade above Porky and the cat. Another sequence of the cat sharpening his knives in tandem to the musical best (and in a solid bout of perspective, too) is framed through the facetious inclusion of an absolutely miserable Porky in the foreground. It’s more amusing than striking visually, but is an effective piece of staging and tries to introduce any possible empathy for Porky (who is largely static in this short) it can.

Our musical sequence arrives to an end through the courtesy of a boxing match with an oxygen balloon. That, too, is a derivative of The Daffy Doc, the only difference being that Daffy was escorted before he could break his makeshift punching bag. Such a mission succeeds here.

Thus, the “climax” is where comparisons between the two cartoon grow most blatant. Clampett directly recycles the animation of the climax from Doc here—one can even spot the awkward attempt of the animator’s attempting to compensate where Porky once fostered a lollipop in his mouth. Rather than drawing his mouth closed, his mouth is agape in a manner that looks conscious and unnatural rather than a genuine indication of his nonplussed suspicion.

Even Porky’s protests of “Hey, eh-wuh-wee-wee-wehh-wuh-eh-what’s the big idea?” are comparatively tired and unmotivated against the same line delivery two years prior. Granted, the voice direction for his tone in general has shifted, his voice having grown deeper (before it would inevitably rise in register again as the years went on), but the energy—or lack thereof in this case—is victim to a noticeable shift.

As has been mentioned so many times before, the climax lacks the spirit of the original due to a disinterest in the character and story. Whereas Daffy’s liberal chorus of shrieks and laughter encouraged a raucous chase scene that prioritized fun and exhilaration first and foremost, the silence of the cat as he repeats Daffy’s same gymnastics feels empty, flat, off-putting. Similar to the openings of both cartoons, Stalling’s music score is foreboding and panicked rather than celebratory.

Doc’s filmmaking was often sympathetic to Daffy, despite his actions (hatched in a warped good faith) not exactly warranting such a favorable light. In Doc, Daffy voices his frustrations, is given ample time to demonstrate his logic and how he arrived to so many conclusions, the music is often indicative of his state of mind (innocently contemplative when searching for a patient, celebratory and wild amidst his fits of hysteria.) He’s indubitably crazy in the cartoon, but there is a certain earnest and emotional attachment in the directing that make his actions compelling and intriguing.

No such privilege is bestowed to the cat here. Music cues often prioritize alarm and moroseness, concocting a sense of unease rather than the jubilation of the former cartoon. Hospitals are not an inherently joyous setting, yet The Daffy Doc repeatedly attempts to make any and all situations lighthearted and innocent, enabling the audience to digest the story and antics with comparative ease. Much of Patient Porky seems to turn its audience off rather than make a pitch to keep them interesting. Even scenes that are invigorating at their core, such as the original climax in Doc, haven been sanitized and sapped of energy. Patient Porky is, politely, a bummer.

Whereas the saw chase in Doc guide Daffy and Porky into an iron lung, the iris engulfing their pulsating bodies, Patient stretches the chase out to accommodate for more reused footage. In this case, shots of Porky retreating to his house are reused from Porky & Daffy—another 1938 entry. Caricature on the speed of both characters running through the streets is genuinely impressive; cutting is fast, whooshing sound effects are loud, trails of smoke serve as the primary indication that someone was running in the first place. Speed is difficult to caricature and manifest effectively, and Clampett does succeed in that regard. Even if such a bright spot is touted only for a few moments.

A few polite laughs do stem from the sincere sense of self assurance exuded by Porky as he waits in his bed. His expression is vacant, stock, which is admittedly more successful in the context than a more specific alternative—the vacancy on his face is a means of confidence in itself. Having the values in the composition and lighting change when the cat opens the door is another clever addition that allows the surroundings to feel more immersive and interactive.

Comments on the appreciation of Porky’s ever earnest conceit are sustained in the way he goes out of his way to maintain eye contact with the cat; he can’t wait to gauge his reaction for whatever undoubtedly clever trick he has up his sleeve.

Through the courtesy of a close-up, Patient Porky does have the honor of exhibiting one of the first (if not the first) “Do Not Open ‘til Christmas” gags in a Warner cartoon. Stalling’s chirpy, domestic sting of “Jingle Bells” is almost mocking in its giddiness; demonstrating the sight gag through a close-up likewise arms it with an innocent importance. The punchline is much more effective through the close-up, seeing as it’s the first opportunity the audience gets to read the text as well. They experience the catch vicariously through the eyes of the cat.

“Christmas?” The floaty timing of the animation as the cat bears a wall-eyed expression of utmost contemplation admittedly serves as a nice compliment, making him feel even more insane.

To watch Porky’s ego crumble and burn in real time is as funny as it is heartbreaking as the cat forces his way next to his patient, triumphantly cooing an “I’ll wait!” to the camera. Juxtaposition between Porky’s visceral horror and his smiley innocence is made all the more effective through the drawing philosophies mentioned above: specific reaction and expression following a non-specific expression. It’s a move that doesn’t entirely seem intentional, but is nevertheless successful. Any and all victories, no matter how small, amount to something for a cartoon such as this one.

I talk a lot of smack about how The Daffy Doc is stupidly superior in every way, Patient Porky is uncompelling in nearly every respect, it’s a cartoon that has no right to exist, etcetera. While I do hold those opinions, I do not think it is truly that awful of a cartoon. If anything, its biggest issue is its painful mediocrity—as we have learned, a “bad” cartoon is still an interesting cartoon, if only for its incompetence. Mediocrity is nothing. Patient Porky is nothing.

Realistically, it’s a short that’s easy to knock on in the year of 2023 with our gift of hindsight and availability of cartoons and cartoon history. With these cartoons being such a limited commodity at the time of their conception, not every theatergoer who saw this cartoon even knew The Daffy Doc existed. They wouldn’t have a basis of comparison, and therefore wouldn’t realize that a much more competent piece of art preceded this one. Likewise, the pop culture references and novelty of crazy characters doing crazy things were still fresh in the minds of the public. It’s a way to kill time before a movie and share a few laughs with other patrons of the theater. At the bare minimum, this cartoon does its job.

With that in mind, it is still unequivocally one of Clampett’s worst cartoons. It is lazy, stilted, uninspired, and the spitting definition of meeting a quota. While easy to default to the “it was a simpler time” excuse regarding the demands of the audience and what they expect in a cartoon, none of the other Warner directors were churning out half baked reprises of previous cartoons to equal ineptitude. Likewise, Clampett has had many other cartoons before this that are much more complex, engaging, funny, and competent. It certainly is true that audiences expected less in those days, just as it’s true Clampett’s intent to pass this off as an entirely independent cartoon would have been more effective, but it still remains that this is a staggeringly sub-par effort that is more of a killjoy than anything.

Regardless (and rather shamefully) it’s a cartoon I can’t bring myself to disavow. If anything, it’s a guilty pleasure cartoon; this short captivated me the first time I saw it because of how utterly odd it is. Like a car crash you can’t avert your eyes to, the idea of such a blatant ripoff existing at such mediocrity was, in a way, compelling and fascinating. I ended up rewatching this one often, and in a span of mere days in-between. I knew it wasn’t good, and to this day I would never kid myself acting as though I have a defense ready for why it’s actually a misunderstood gem.

It isn’t a good cartoon. That won’t stop me from loving the song number, nor will it impede my amusement of the sight gag of a birthday disaster lodged in Porky’s stomach or the endearing, almost accidental smugness as he thinks he has the upper hand over the cat at the end. I probably have more compliments to pay to this short than any other person, but it is easily a cartoon that is one of Clampett’s weakest and has no genuine reason to exist.

.gif)